Image created with Bing AI. Prompt: “a surreal painting of a coin flip with a question mark over the coin. The coin represents the p-value, the probability of getting heads if the coin is fair. The painting shows the uncertainty and controversy around this statistical concept.”

In this course, it may occur to you that we don’t place as much emphasis on p-values as you might expect from a discipline which makes ample use of concepts from applied statistics. P-values are widely used in many disciplines and are a hallmark of hypothesis testing. However, you shouldn’t judge the performance or explainability of a model from the p-values of the coefficients alone, as they are not the ultimate proof of a hypothesis.

What are p-values?

P-values, short for “probability-values”, are a statistical measure used to determine the strength of evidence against a null hypothesis. In hypothesis testing, the null hypothesis represents the absence of the claim or effect put forward by the alternative hypothesis, which is the hypothesis we are trying to prove and which is accepted if we have enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

P-values quantify the strength of this evidence; the smaller the p-value, the stronger the evidence. A small p-value is not equal to the probability of the null hypothesis being false but indicates the probability of obtaining a result at least as large as those observed if the null hypothesis were true.

How are p-values used?

The use of p-values in hypothesis testing is prevalent among statisticians, researchers, and economists. The concept of ‘statistical significance’ assessed using p-values is commonly used to support a study’s conclusion. The idea of significance testing evolved from the statistician R. A. Fisher, in the 1930s. He advocated for \(p < 0.05\) as a standard level for concluding that there is significant statistical evidence against the null hypothesis. P-values of less than 0.05 have since been considered the ‘gold standard’ of significance, leading many scientists and researchers to pursue \(p < 0.05\) as the ultimate goal of scientific research where, in reality, this is just a threshold that someone decided on.

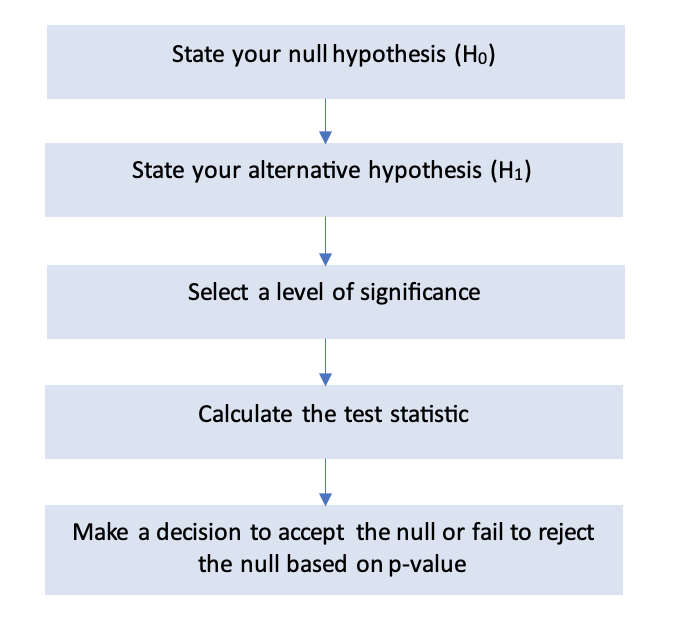

A researcher can begin a hypothesis test by following the steps below. Let’s say that they chose a 5% significance level to test whether a model has a relationship between variables. They conduct a statistical test and calculate the p-values. If it is less than 0.05, they can conclude that the results would rarely (but not never) occur by chance alone if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, the null hypothesis, which in this case is the claim that there is no relationship between variables, is rejected.

However, a p-value of less than 0.05 does not mean there’s less than a 5% chance your experimental results are due to random chance. A p-value of less than 0.05 means that there is less than a 5% chance of seeing these results (or more extreme results), in a world where the null hypothesis is true.

Another fiddly caveat is that as rejecting your null hypothesis indirectly suggests support for the alternative one, the results of a hypothesis test, even with a small p-value, do not definitely prove that your alternative hypothesis is correct.

Misuse of p-values

The trickiness of these distinctions has led to the common misuse of p-values. Alongside misrepresenting p-values as a result of misunderstanding the distinctions above, the importance placed on p-values has led to researchers ‘p-hacking’ – manipulating their data or analysis to obtain a low p-value and an easy ticket into an academic journal.

Articles written about this specific topic including “Science Isn’t Broken” mention how at least one journal has decided it has had enough of the overreliance on p-values. Journals such as Basic and Applied Social Psychology announced they will no longer publish p-values, stating that that the p < 0.05 bar is too easy to pass, and leads to lower quality research. The threshold value of 0.05 itself is arbitrary, taken simply as convention after Fisher advocated for its use. This has led to researchers disregarding results with a p-value greater than 0.05. Not finding any evidence of difference does not mean that there is no difference – this could be down to poor study design, a small sample size, or imprecise measurements.

Not the ultimate proof of a hypothesis

Ultimately, a p-value is just a statistic, not a sign from above. As the updated requirements for the Basic and Applied Social Psychology journal suggest, the validity of a scientific conclusion should rely on more than the results of the statistical analysis itself.

In this course it is therefore crucial to validate models with respect to other metrics like MAE, accuracy, precision, recall, or F1 score, to name a few. These and other metrics offer a more comprehensive assessment, and while they can be used in conjunction with p-values, ensure that models are evaluated not only in terms of their statistical performance, but also their practical and real-world relevance.