🖥️ Week 03 Lecture

From Notebook to Scrapy Project

Last Updated: 01 February 2026

I won’t use slides in this lecture. Instead, I will do some live demos and we will make collective decisions in-class about how we want our project to look like and evolve. Follow along if you like, but focus on understanding the structure and the flow. You will have time to do the same in the lab.

📍 Session Details

- Date: Monday, 2 February 2026

- Time: 16:00 - 18:00

- Location: SAL.G.03

📋 Preparation

All you need to do really is to make some progress on the web scraping part of ✍️ Problem Set 1 as you can. Bring any challenges you are facing so we can make decisions that make your life easier.

We will discuss some news pieces, too, but it’s OK if you don’t read them in advance. We can read and discuss them in class.

What we will cover

Technical

We will move away from exploring code in notebooks to building a full Scrapy project:

- Project structure: Why we use

scrapy startprojectinstead of a single script. - Crawling: How spiders follow links and chain

parsemethods with callbacks. - Pipelines: How to clean and validate data after extraction.

- Scrapy and Selenium: Where browser automation fits when a site needs JavaScript.

- Git workflow: How to refactor a script into a project with sensible commits.

In-class discussions and collective decisions

We will discuss news about scraping ethics (AI companies, publishers, small sites) and think about how that relates to our project (the ✍️ Problem Set 1) and work together on a CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md for the project.

👉 The articles below are selections of topics we will discuss. It’s ok if you don’t have time to read them in advance. We will look at them in class only.

Readings

- Bobby Allyn (14 January 2025). The New York Times takes OpenAI to court. ChatGPT’s future could be on the line. NPR.

- Sarah Emerson (7 June 2024). Buzzy AI Search Engine Perplexity Is Directly Ripping Off Content From News Outlets. Forbes (LSE login).

- Randall Lane (11 June 2024). Why Perplexity’s Cynical Theft Represents Everything That Could Go Wrong With AI. Forbes.

- Julie Bort (10 January 2025). How OpenAI’s bot crushed this seven-person company’s website ‘like a DDoS attack’. TechCrunch.

📖 Guide 1: Setting up your GitHub repository

In case you haven’t set up your GitHub repository yet for the ongoing ✍️ Problem Set 1, let’s do it now.

1.1 Clone your repository

If you have accepted the assignment, you have a GitHub repository for Problem Set 1. The ✍️ Problem Set 1 page explains how to accept it and get your repo URL.

Your repository lives at:

https://github.com/lse-ds205/problem-set-1-<github-username>

Important note about placeholders

When we write things like <github-username> in the text, it means that you need to replace it with your actual GitHub username. Replace the whole thing, including the angle brackets < and >, with your actual username. For example, if your username is jonjoncardoso, your URL is:

https://github.com/lse-ds205/problem-set-1-jonjoncardoso

From a Terminal, clone the repo (use the URL that matches your username, or the SSH URL from GitHub after accepting):

git clone git@github.com:lse-ds205/problem-set-1-<github-username>.git1.2 Open the project in your environment

After cloning, open a Terminal and change into the project directory. On Nuvolos (where most of you will work), the clone will appear under /files/. Your project path will be:

/files/problem-set-1-<your-github-username>

So for example:

cd /files/problem-set-1-jonjoncardoso💡 TIP: When writing commands in the Terminal, you do not need to always type the full path to a file or folder. Just start typing /files/pro and press TAB; the shell will autocomplete. If several folders match, keep pressing TAB to cycle through them.

1.3 Maintaining your repository

As you work on your project, you will need to make changes to your repository. Revisit the Git concepts highlighted in the 4️⃣ Git & GitHub guide.

📖 Guide 2: Setting up your Scrapy project

You might have already started working on the scraper for ✍️ Problem Set 1 and you likely used a single Jupyter Notebook to do so, in line with what we did in 💻 W02 Lab.

From now on, though, we will be working with a Scrapy project, a more structured and professional way to work on scraping tasks.

2.1 Create the Scrapy project

From the project root (the folder that contains your cloned repo, e.g. problem-set-1-jonjoncardoso), run:

scrapy startproject supermarkets ./scraper/On Windows (PowerShell), use backslashes:

scrapy startproject supermarkets .\scraper\That command creates a Scrapy project named supermarkets inside a scraper/ folder. The directory containing scrapy.cfg is the project root for Scrapy; here it is scraper/.

2.2 What gets created

After running scrapy startproject supermarkets ./scraper/, you will see:

scraper/

├── scrapy.cfg

└── supermarkets/

├── __init__.py

├── items.py

├── middlewares.py

├── pipelines.py

├── settings.py

└── spiders/

├── __init__.py

└── (your spider files go here)| File or folder | Role |

|---|---|

| scrapy.cfg | Tells the scrapy command which settings module to use (e.g. supermarkets.settings). |

| supermarkets/ | Python package for this Scrapy project. |

| items.py | Defines the structure of the data you scrape (field names and types). |

| settings.py | Project-wide options: bot name, delays, which pipelines and middlewares are on. |

| pipelines.py | Item pipelines: each scraped item is passed through these in order for cleaning, validation, and saving (e.g. to CSV or a database). |

| middlewares.py | Hooks into the request/response flow: downloader middlewares (before/after HTTP) and spider middlewares (around the spider). Optional; used e.g. for Selenium. |

| spiders/ | Folder where your spider classes live. Each spider defines name, start_urls, and parse() (or other callbacks) to decide which pages to fetch and what data to extract. |

Notice that spiders/ is empty except for __init__.py. The next section shows how to create your first spider.

2.3 Create a spider

Change into the scraper/ directory first:

cd scraperThen use scrapy genspider to create a spider file:

scrapy genspider waitrose www.waitrose.comThis creates supermarkets/spiders/waitrose.py with the following boilerplate:

import scrapy

class WaitroseSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = "waitrose"

allowed_domains = ["www.waitrose.com"]

start_urls = ["https://www.waitrose.com"]

def parse(self, response):

passLet’s break down what each part does:

| Attribute | Purpose |

|---|---|

name |

The identifier you use when running the spider: scrapy crawl waitrose |

allowed_domains |

Scrapy will only follow links within these domains. Prevents accidentally crawling the entire internet. |

start_urls |

The URLs Scrapy fetches first. Your parse() method receives the responses. |

parse() |

The method Scrapy calls when a response arrives. You write your extraction logic here. |

For ✍️ Problem Set 1, you’ll want to change start_urls to point to the groceries page:

start_urls = ["https://www.waitrose.com/ecom/shop/browse/groceries"]You can now run your spider from the scraper/ directory:

scrapy crawl waitroseNothing will happen yet because parse() is empty. But Scrapy will fetch the page and call your method. The next step is writing the extraction logic inside parse().

You can also pass a URL as a command-line argument if you want to test a specific page:

scrapy crawl waitrose -a url=https://www.waitrose.com/ecom/shop/browse/groceries/beer_wine_spiritsThis requires adding a small __init__ method to your spider to accept the argument. We’ll cover this pattern in the lab.

2.4 How Scrapy fits together

When you move out of a notebook and start working with Scrapy’s project structure, the way you think about your scraper changes. You no longer write a loop that fetches pages one by one, handles retries when requests fail, or tracks which URLs you’ve already visited. Scrapy handles that for you. Your job becomes: given a page, what do I extract and where do I go next?

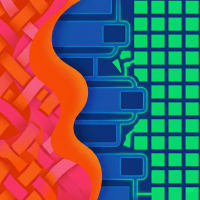

The diagram below shows this division of labour.

When you run scrapy crawl waitrose, Scrapy’s Engine takes over. It calls your spider’s start_requests() method (or uses start_urls to generate requests automatically), queues those requests, and when responses come back, it calls your parse() method. Your code reacts to responses; the Engine decides when to call it.

The grey boxes (Scheduler, Downloader) are Scrapy internals you don’t touch. The pink Engine orchestrates everything but is invisible in your code. You write the blue (Spider) and green (Pipeline) parts. Middleware sits at the boundary: Scrapy provides defaults, but you can customise it in middlewares.py when you need something like Selenium.

Learn more about it on the official Scrapy architecture documentation (which has its own diagram).

2.5 What changes in your code

Extracting data

In your notebook, you wrote requests.get(url) to fetch a page, then created a Selector to extract data. In a Scrapy spider, you skip both steps. Scrapy fetches the page and hands you a response object that already has .css() and .xpath() methods.

Before (notebook):

response = requests.get(url)

sel = Selector(text=response.content)

title = sel.css('h1::text').get()After (spider):

def parse(self, response):

title = response.css('h1::text').get()

yield {'title': title}The selectors work exactly the same way. The difference is where the response comes from: you don’t fetch it yourself.

What is this yield keyword?

In a simplistic way, just think of it as the same as the return keyword at the end of a Python function. This signals that the code will not continue after the yield statement and it will return something to whatever piece of code that called this function.

The major difference is that a yield statement can be called multiple times, returning a sequence of values. Formally, it produces what is called a generator.

Generators are a type of lazy evaluation, something that allows you to calculate and returnvalues only when they are needed.

Following links

In a notebook, if you wanted to visit another page, you’d loop through URLs and call requests.get() again. In a Scrapy spider, you yield a Request object and tell Scrapy which method to call when that page loads:

def parse(self, response):

# Extract data from the current page

yield {'title': response.css('h1::text').get()}

# Follow a link to another page

next_url = response.css('a.next-page::attr(href)').get()

if next_url:

yield scrapy.Request(next_url, callback=self.parse)The callback argument tells Scrapy which method handles the response. Here it’s self.parse again, so the same logic runs on every page. For different page types (listing vs product detail), you’d use different callbacks:

def parse(self, response):

# This handles listing pages

for product_link in response.css('a.product::attr(href)').getall():

yield scrapy.Request(product_link, callback=self.parse_product)

def parse_product(self, response):

# This handles individual product pages

yield {

'name': response.css('h1::text').get(),

'price': response.css('.price::text').get(),

}Scrapy queues these requests, fetches them when ready, and calls the right method for each response. You don’t manage the queue or track which pages you’ve visited.

The other files (pipelines.py, middlewares.py, items.py) come into play once your basic spider works. We’ll add those in the lab.

After the Lecture

The W03 lab continues with Scrapy project structure and pipelines. Keep pushing on ✍️ Problem Set 1: your scraper will be handed to another student in W05, so clear structure and documentation matter.