✅ Tutorial solution: tidymodels recipes and workflows

From orange juice 🍊 to food delivery 🛵

1 Introduction

Modern data analysis is much more than “fit a model.”

Before a model can learn, we must understand the problem, prepare and clean the data, train, and evaluate it fairly and repeatably.

The tidymodels ecosystem in R provides a unified grammar for all these steps.

In this assignment you will:

- explore how recipes describe and execute data-preparation steps,

- see how workflows bundle preprocessing and modeling together to prevent data leakage, and

- practice building, validating, and comparing models on two datasets.

We begin with a small orange juice dataset 🍊 to introduce tidymodels concepts clearly,

then move on to a larger, more realistic food delivery dataset 🛵.

2 🎯 Learning objectives

By the end of this assignment, you will be able to:

- explain what

tidymodelsrecipes and workflows are and why they prevent leakage,

- build preprocessing recipes that handle categorical and numeric variables safely,

- combine preprocessing and modeling inside workflows,

- evaluate models with both random and time-aware cross-validation,

- tune and compare model types (e.g. LightGBM, SVM, regularized regression),

- engineer meaningful features such as distance and speed, and

- address class imbalance through undersampling and oversampling.

3 ⚙️ Set-up

3.1 Download dataset and solution notebook

You can download the dataset used from section 5 of this tutorial by clicking on the button below:

Just like with all data in this course, place this new dataset into the data folder you created a few weeks ago.

You can also download the notebook that goes with this tutorial by clicking the button below:

3.2 Install needed libraries

install.packages('ISLR2')

install.packages('geosphere')

install.packages('lightgbm')

install.packages('bonsai')

install.packages('vip')or if you have the librarian library installed:

librarian::shelf(ISLR2,geosphere,lightgbm,bonsai,vip)3.3 Import needed libraries

library(tidymodels)

library(ISLR2)

library(tidyverse)

library(lubridate)

library(geosphere)

library(bonsai) # required for engine = "lightgbm"

library(ggplot2)The tidymodels core packages (like parsnip) define the modeling interface but not every possible engine.

Support for LightGBM is provided by an extension package called bonsai, which connects tree-based algorithms like LightGBM and CatBoost to the tidymodels syntax.

4 🍊 Orange-juice warm-up

The aim of this section is to understand the logic of tidymodels through a compact, complete example.

You will predict which brand of orange juice a customer buys—Citrus Hill (CH) or Minute Maid (MM)—using price, discounts, and loyalty information.

4.1 Load and explore the data

data(OJ)

glimpse(OJ)Rows: 1,070

Columns: 18

$ Purchase <fct> CH, CH, CH, MM, CH, CH, CH, CH, CH, CH, CH, CH, CH, CH,…

$ WeekofPurchase <dbl> 237, 239, 245, 227, 228, 230, 232, 234, 235, 238, 240, …

$ StoreID <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 1, 2, 2…

$ PriceCH <dbl> 1.75, 1.75, 1.86, 1.69, 1.69, 1.69, 1.69, 1.75, 1.75, 1…

$ PriceMM <dbl> 1.99, 1.99, 2.09, 1.69, 1.69, 1.99, 1.99, 1.99, 1.99, 1…

$ DiscCH <dbl> 0.00, 0.00, 0.17, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0…

$ DiscMM <dbl> 0.00, 0.30, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.40, 0.40, 0.40, 0…

$ SpecialCH <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0…

$ SpecialMM <dbl> 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0…

$ LoyalCH <dbl> 0.500000, 0.600000, 0.680000, 0.400000, 0.956535, 0.965…

$ SalePriceMM <dbl> 1.99, 1.69, 2.09, 1.69, 1.69, 1.99, 1.59, 1.59, 1.59, 1…

$ SalePriceCH <dbl> 1.75, 1.75, 1.69, 1.69, 1.69, 1.69, 1.69, 1.75, 1.75, 1…

$ PriceDiff <dbl> 0.24, -0.06, 0.40, 0.00, 0.00, 0.30, -0.10, -0.16, -0.1…

$ Store7 <fct> No, No, No, No, Yes, Yes, Yes, Yes, Yes, Yes, Yes, Yes,…

$ PctDiscMM <dbl> 0.000000, 0.150754, 0.000000, 0.000000, 0.000000, 0.000…

$ PctDiscCH <dbl> 0.000000, 0.000000, 0.091398, 0.000000, 0.000000, 0.000…

$ ListPriceDiff <dbl> 0.24, 0.24, 0.23, 0.00, 0.00, 0.30, 0.30, 0.24, 0.24, 0…

$ STORE <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 2, 2…Each row describes sales of orange juice for one week in one store. The outcome variable is Purchase, which records whether the customer bought CH or MM.

Other important variables include:

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

PriceCH, PriceMM |

prices of Citrus Hill and Minute Maid |

DiscCH, DiscMM |

discounts for each brand |

LoyalCH |

loyalty toward Citrus Hill |

STORE, WeekofPurchase |

store ID and week number |

4.2 Sampling and stratified splitting

The full dataset has just over a thousand rows. To simulate a smaller study, we take a sample of 250 rows and then split it into training and test sets (60 % / 40 %). Because Purchase is categorical, we stratify so the CH/MM ratio remains constant.

Why 60/40 instead of 80/20? When the dataset is small, an 80/20 split leaves very few test examples, making metrics unstable. A 60/40 split provides enough data to train while still leaving a meaningful number of unseen samples for evaluation.

set.seed(123)

oj_sample_split <- initial_split(OJ, prop = 250 / nrow(OJ), strata = Purchase)

oj_sample <- training(oj_sample_split)

oj_split <- initial_split(oj_sample, prop = 0.6, strata = Purchase)

oj_train <- training(oj_split)

oj_test <- testing(oj_split)

bind_rows(

OJ |> count(Purchase) |> mutate(prop = n/sum(n), set = "Full"),

oj_sample |> count(Purchase) |> mutate(prop = n/sum(n), set = "Sample 250"),

oj_train |> count(Purchase) |> mutate(prop = n/sum(n), set = "Train 60%"),

oj_test |> count(Purchase) |> mutate(prop = n/sum(n), set = "Test 40%")

) Purchase n prop set

1 CH 653 0.6102804 Full

2 MM 417 0.3897196 Full

3 CH 152 0.6104418 Sample 250

4 MM 97 0.3895582 Sample 250

5 CH 91 0.6107383 Train 60%

6 MM 58 0.3892617 Train 60%

7 CH 61 0.6100000 Test 40%

8 MM 39 0.3900000 Test 40%Stratification ensures that both training and testing subsets keep the same mix of CH and MM. Without it, we could train mostly on one brand and evaluate on another—a subtle form of bias. Think of the dataset as a smoothie: 60 % orange 🍊 and 40 % mango 🥭. Every smaller glass should taste the same.

4.3 Feature engineering: add a season variable

WeekofPurchase records when the purchase occurred. Week numbers by themselves are not very informative, but they can reveal seasonal patterns—for instance, one brand might sell better in summer.

We’ll create a new column season based on week number and keep WeekofPurchase as a non-predictor identifier.

oj_train <- oj_train |>

mutate(

season = case_when(

WeekofPurchase %% 52 < 13 ~ "Winter",

WeekofPurchase %% 52 < 26 ~ "Spring",

WeekofPurchase %% 52 < 39 ~ "Summer",

TRUE ~ "Fall"

)

)

oj_test <- oj_test |>

mutate(

season = case_when(

WeekofPurchase %% 52 < 13 ~ "Winter",

WeekofPurchase %% 52 < 26 ~ "Spring",

WeekofPurchase %% 52 < 39 ~ "Summer",

TRUE ~ "Fall"

)

)4.4 Understanding recipes

A recipe is a plan describing exactly how data should be prepared before modeling. It bundles all preprocessing steps so they can be applied identically across training, testing, and resampling.

Here is a complete recipe for our orange-juice problem:

oj_rec <- recipe(Purchase ~ PriceCH + PriceMM + DiscCH + DiscMM +

LoyalCH + STORE + season + WeekofPurchase,

data = oj_train) |>

update_role(WeekofPurchase, new_role = "ID") |> # keep but do not model

step_dummy(all_nominal_predictors()) |> # encode categoricals

step_center(all_numeric_predictors()) |> # subtract mean

step_scale(all_numeric_predictors()) # divide by SD4.4.1 Center vs scale vs normalize

step_center()subtracts each variable’s mean so values are centered at 0.step_scale()divides by standard deviation so units are comparable.step_normalize()combines both operations in a single step.

Why standardize? Models such as logistic regression, SVMs, and KNN are sensitive to variable scales. Standardizing puts all numeric predictors on a common footing and stabilizes optimization.

4.5 Choose a model

We will use logistic regression for this classification task.

oj_mod <- logistic_reg() |> set_engine("glm")4.6 Build a workflow

A workflow combines preprocessing and modeling so that the correct steps are always applied in the correct order.

oj_wf <- workflow() |>

add_recipe(oj_rec) |>

add_model(oj_mod)4.7 Fit and evaluate the model

oj_fit <- oj_wf |> fit(data = oj_train)

oj_probs <- predict(oj_fit, oj_test, type = "prob")

oj_class <- predict(oj_fit, oj_test)

oj_preds <- bind_cols(oj_test |> select(Purchase), oj_probs, oj_class)

# class-based metrics

class_metrics <- metric_set(f_meas, precision, recall)

class_metrics(oj_preds,

truth = Purchase,

estimate = .pred_class)

# probability-based metric

roc_auc(oj_preds, truth = Purchase, .pred_CH)# A tibble: 3 × 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 f_meas binary 0.887

2 precision binary 0.873

3 recall binary 0.902

roc_auc(oj_preds, truth = Purchase, .pred_CH)

# A tibble: 1 × 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 roc_auc binary 0.9234.7.1 How fit() and predict() work

When you call fit(), tidymodels first trains the recipe on the training data: it computes the statistics required for preprocessing—means and standard deviations for scaling, the set of levels for categorical variables, etc.—and stores them inside the workflow. It then fits the model (here, a logistic regression) to the processed training data.

Later, predict() re-applies the trained recipe to the test data using those same stored statistics. No new averages or encodings are computed; the test data remain unseen during training. This is what prevents data leakage—the model never peeks at future information.

4.7.2 Choosing appropriate metrics

Because the classes are not perfectly balanced, accuracy can be misleading. A model that always predicts the majority class might look “accurate” but tell us little. Instead we evaluate:

- Precision: when the model predicts

CH, how often is it correct? - Recall: of all actual

CHpurchases, how many did it find? - F₁-score: the harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing both.

- ROC AUC: the area under the ROC curve, summarizing discrimination across thresholds.

These measures together give a more complete picture of performance.

- Replace

logistic_reg()with another classifier you know, such asrand_forest()orsvm_rbf(). - Rerun the recipe, workflow, and evaluation.

- Compare F₁ and ROC AUC. Which model performs better, and why might that be?

rf_spec <- rand_forest(trees = 500) |>

set_engine("ranger") |>

set_mode("classification")

rf_wf <- workflow() |>

add_recipe(oj_rec) |>

add_model(rf_spec)

rf_fit <- rf_wf |> fit(data = oj_train)

rf_probs <- predict(rf_fit, oj_test, type = "prob")

rf_class <- predict(rf_fit, oj_test)

rf_preds <- bind_cols(oj_test |> select(Purchase), rf_probs, rf_class)

metric_set(f_meas, precision, recall)(

rf_preds,

truth = Purchase,

estimate = .pred_class

)

roc_auc(rf_preds, truth = Purchase, .pred_CH)Output

# A tibble: 3 × 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 f_meas binary 0.869

2 precision binary 0.869

3 recall binary 0.869

# A tibble: 1 × 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 roc_auc binary 0.913The logistic regression performs slightly better overall, with a higher F₁-score (0.887 vs. 0.869) and ROC AUC (0.923 vs. 0.913). This makes sense for the orange juice problem: the relationship between price, discounts, and brand choice is mostly linear and additive, which logistic regression captures very well.

Random forests can model nonlinearities, but with relatively few features and a small dataset, that extra flexibility doesn’t help much—and can even add a bit of noise. So, the simpler model wins here for both interpretability and performance.

💭 With this said, would you do the model evaluation differently? What might you add here?

5 Food delivery dataset 🛵

You are now ready to apply the same ideas to a realistic dataset.

We will use a public Food Delivery dataset from Kaggle containing restaurant, delivery-person, and environmental details along with the delivery time in minutes (we’re using the dataset called train on Kaggle).

Your objectives are to:

- Predict delivery time (

Time_taken(min)) using regression.

- Compare cross-sectional and time-aware validation.

- Later, classify deliveries by speed.

5.1 Load and explore the data

food <- read_csv("data/food-delivery.csv") |>

mutate(

Order_Date = dmy(Order_Date),

Order_Week = isoweek(Order_Date)

) |>

arrange(Order_Date)

glimpse(food)Rows: 45,593

Columns: 21

$ ID <chr> "0xd936", "0xd681", "0xc606", …

$ Delivery_person_ID <chr> "GOARES15DEL02", "GOARES07DEL0…

$ Delivery_person_Age <dbl> 26, 38, 20, 39, 20, 33, 21, 29…

$ Delivery_person_Ratings <dbl> 4.3, 4.9, 4.5, 4.7, 4.8, 4.6, …

$ Restaurant_latitude <dbl> 15.51315, 15.56129, 0.00000, 2…

$ Restaurant_longitude <dbl> 73.78346, 73.74948, 0.00000, 8…

$ Delivery_location_latitude <dbl> 15.56315, 15.60130, 0.05000, 2…

$ Delivery_location_longitude <dbl> 73.83346, 73.78948, 0.05000, 8…

$ Order_Date <date> 2022-02-11, 2022-02-11, 2022-…

$ Time_Orderd <chr> "23:25:00", "13:35:00", "21:10…

$ Time_Order_picked <time> 23:35:00, 13:40:00, 21:25:00,…

$ Weatherconditions <chr> "conditions Sandstorms", "cond…

$ Road_traffic_density <chr> "Low", "High", "Jam", "Low", "…

$ Vehicle_condition <dbl> 0, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, …

$ Type_of_order <chr> "Buffet", "Drinks", "Drinks", …

$ Type_of_vehicle <chr> "motorcycle", "scooter", "moto…

$ multiple_deliveries <dbl> 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, …

$ Festival <chr> "No", "No", "No", "No", "No", …

$ City <chr> "Urban", "Urban", "Metropoliti…

$ `Time_taken(min)` <chr> "(min) 21", "(min) 25", "(min)…

$ Order_Week <dbl> 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, …The dataset includes restaurant and delivery coordinates, information about the delivery person, weather, traffic, and more. We first convert Order_Date from a string into a proper Date object using dmy() so R recognizes it as a date. Then we create Order_Week (the ISO week number) to group all orders from the same week.

Why group by week rather than day or month? Daily data can be too granular—many days may have only a few deliveries—whereas monthly data hide short-term fluctuations. Grouping by week is a reasonable middle ground for time-aware validation later.

The variable Time_taken(min) is stored as text values such as "(min) 21". Convert it to numeric values like 21 using a suitable string operation and transformation.

💡 Question: Why do you think this conversion is important before modeling?

food <- food |>

mutate(`Time_taken(min)` = as.numeric(str_remove(`Time_taken(min)`, "\\(min\\)\\s*")))

# quick check

food %>% summarise(is_num = is.numeric(`Time_taken(min)`))Output

# A tibble: 1 × 1

is_num

<lgl>

1 TRUEWhy it matters: Models expect numeric targets for regression; leaving it as text would break training or silently coerce with NAs. We also need Time_taken(min) to be numerical as missingness checks run on character columns might be incorrect and assume the variable has no missing values when it has (“” is considered a value so not missing when it comes to characters!).

5.2 Create a seasonal feature

While Order_Week captures time numerically, sometimes it’s more interpretable to group weeks into seasons. Since all orders here fall between February and April, we can label them roughly as “late winter” or “early spring.”

food <- food |>

mutate(

Season = case_when(

Order_Week %in% 1:13 ~ "Winter", # Weeks 1–13 (approx. Jan–Mar)

Order_Week %in% 14:26 ~ "Spring", # Weeks 14–26 (Apr–Jun)

Order_Week %in% 27:39 ~ "Summer", # Weeks 27–39 (Jul–Sep)

Order_Week %in% 40:52 ~ "Autumn", # Weeks 40–52 (Oct–Dec)

TRUE ~ NA_character_

)

)You can then decide whether to:

- Use

Seasonas a categorical predictor (it will be converted into dummy variables by your recipe), or - Treat it as a non-predictor context variable using

update_role(Season, new_role = "ID").

Both approaches are valid, depending on your modeling goal.

Creating seasonal or cyclical indicators helps the model capture periodic effects (for instance, delivery conditions in early spring vs. late winter) without memorizing specific weeks.

5.3 Compute a simple distance feature

Delivery time should depend strongly on distance. We can approximate distance using the Haversine formula, which computes the great-circle (shortest) distance between two points on Earth.

food <- food |>

mutate(distance_km = distHaversine(

cbind(Restaurant_longitude, Restaurant_latitude),

cbind(Delivery_location_longitude, Delivery_location_latitude)

) / 1000)Even a rough, straight-line distance captures a large share of the variation in delivery times. It reflects the physical effort of travel even when we do not model exact routes or traffic lights.

Each distance_km value depends only on its own row (restaurant and delivery coordinates). No information is averaged or shared across the dataset, so calculating this feature before splitting does not cause leakage.

5.4 Create time-of-day features

Delivery times don’t depend solely on distance or traffic — they also vary throughout the day. Morning commutes, lunch peaks, and late-night orders each impose different operational pressures on both restaurants and delivery drivers.

We’ll capture these daily patterns by creating new variables describing the time of order placement and time of pickup, both as numeric hours and as interpretable day-part categories.

food <- food |>

mutate(

# Clean invalid or empty time strings

Time_Orderd = na_if(Time_Orderd, "NaN"),

Time_Orderd = na_if(Time_Orderd, ""),

Time_Orderd = na_if(Time_Orderd, "null"),

Time_Orderd = na_if(Time_Orderd, "0"),

# Then safely extract hours, using suppressWarnings() to ignore harmless NAs

Order_Hour = suppressWarnings(lubridate::hour(hms::as_hms(Time_Orderd))),

Pickup_Hour = suppressWarnings(lubridate::hour(hms::as_hms(Time_Order_picked))),

# Categorical time-of-day bins (use the numeric hours we just extracted)

Time_of_Day = case_when(

Pickup_Hour >= 5 & Pickup_Hour < 12 ~ "Morning",

Pickup_Hour >= 12 & Pickup_Hour < 17 ~ "Afternoon",

Pickup_Hour >= 17 & Pickup_Hour < 22 ~ "Evening",

TRUE ~ "Night"

),

Order_Time_of_Day = case_when(

is.na(Order_Hour) ~ NA_character_,

Order_Hour >= 5 & Order_Hour < 12 ~ "Morning",

Order_Hour >= 12 & Order_Hour < 17 ~ "Afternoon",

Order_Hour >= 17 & Order_Hour < 22 ~ "Evening",

TRUE ~ "Night"

)

)⚠️ Some entries in Time_Orderd are invalid (e.g., "NaN", "", or "0") and can’t be converted to clock times. To avoid errors, we explicitly set these to NA before parsing. Missing times are later handled by the recipe’s step_impute_bag(), which fills them using information from other predictors.

When deriving categorical summaries from numeric variables (like converting Order_Hour to Order_Time_of_Day), you must explicitly preserve missingness.

By default, case_when() assigns the “else” case (TRUE ~ ...) even when inputs are missing. This can make downstream missingness disappear artificially, hiding real data problems.

If Order_Hour is missing because the original Time_Orderd was invalid or blank, we should preserve that NA in the derived column — otherwise, the model might think those rows are “Night” orders!

5.4.1 🌆 Why this matters

Raw timestamps like "13:42:00" are hard for models to interpret: they’re too granular, cyclical (23:59 ≈ 00:01), and numerically meaningless. By extracting hour values and day-part categories, we make time information explicit and interpretable.

| Feature | Type | Operational meaning | Expected effect on delivery time |

|---|---|---|---|

Order_Hour |

Numeric (0–23) | The exact hour when the customer placed the order | Reflects demand cycles — lunch (12–14h) and dinner (19–21h) peaks increase restaurant load and prep time. |

Pickup_Hour |

Numeric (0–23) | The exact hour when the courier picked up the order | Reflects road and traffic conditions — peak commute hours (8–10h, 17–20h) slow travel. |

Order_Time_of_Day |

Categorical (Morning/Afternoon/Evening/Night) | Coarse summary of restaurant-side demand | Morning orders (e.g., breakfast deliveries) tend to be faster; dinner rushes slower. |

Time_of_Day |

Categorical (Morning/Afternoon/Evening/Night) | Coarse summary of driver-side conditions | Evening and night deliveries face heavier congestion and longer travel times. |

5.4.2 💡 How these features work together

The order and pickup stages represent two distinct time-sensitive parts of the end-to-end delivery process:

| Stage | Key processes | Feature(s) | What it captures |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Order placement → pickup | Kitchen preparation, queueing, and coordination delays | Order_Hour, Order_Time_of_Day |

Busy restaurant periods (e.g., lunch) slow down order readiness. |

| 2. Pickup → delivery completion | Driving, navigation, and drop-off conditions | Pickup_Hour, Time_of_Day |

Traffic congestion, daylight, and road conditions affect delivery speed. |

Together, these features let the model separate restaurant-side delays from driver-side delays — two sources that are often conflated in the overall Time_taken(min) target.

🧩 For example:

- Orders placed at 12:00 but picked up at 12:40 suggest restaurant bottlenecks.

- Deliveries picked up at 18:00 tend to face evening rush-hour slowdowns, even for the same distance.

This dual-stage representation helps the model uncover more realistic, interpretable patterns in how delivery times fluctuate across the day.

5.4.3 🕐 Why keep both numeric and categorical forms?

| Representation | Strength | When it helps |

|---|---|---|

Numeric (Order_Hour, Pickup_Hour) |

Retains the continuous structure of time (e.g., 10 → 11 → 12), enabling models to learn smooth nonlinear effects. | Particularly useful for tree-based models (like LightGBM) that can detect thresholds or local increases. |

Categorical (Order_Time_of_Day, Time_of_Day) |

Encodes interpretable shifts between broad periods (morning vs evening) and captures discontinuous behavior (e.g., lunch/dinner rushes). | Helpful for communicating and visualizing time effects and for linear models needing explicit contrasts. |

Tree-based models can seamlessly decide which variant carries the stronger signal for prediction.

5.5 Create a cross-sectional dataset and training/test split

A cross-sectional analysis takes one time period and treats all observations within it as independent. We will use the busiest week (the one with the most orders).

week_counts <- food |> count(Order_Week, sort = TRUE)

cross_df <- food |>

filter(Order_Week == first(week_counts$Order_Week))Why the busiest week? It provides enough examples for both training and validation within a consistent operational context (similar traffic, weather, and demand). Smaller weeks may have too few deliveries to form stable training and test sets, and combining non-adjacent weeks might mix different traffic or weather patterns. This design isolates one dense period to study model behavior without temporal drift.

Split the cross_df data into training and test sets. Use about 80 % of the data for training and 20 % for testing. Set a random seed for reproducibility.

set.seed(42)

cross_split <- initial_split(cross_df, prop = 0.8)

cross_train <- training(cross_split)

cross_test <- testing(cross_split)

# quick sanity check

nrow(cross_train) / nrow(cross_df)Output

[1] 0.79997355.6 Handle missing data with bagged-tree imputation

Only a few predictors contain missing data:

Delivery_person_RatingsDelivery_person_Agemultiple_deliveries

Rather than filling these with simple averages or modes, we will impute them using bagged-tree models.

5.6.1 What is bagged-tree imputation?

Bagging stands for bootstrap aggregation. It works as follows:

- Draw multiple bootstrap samples from the available (non-missing) data. Each bootstrap sample is drawn with replacement, meaning some observations appear more than once while others are left out.

- Fit a small decision tree to each bootstrap sample to predict the missing variable from all others.

- For each missing entry, average the predictions across all trees.

Because each tree sees a slightly different subset, their averaged predictions are more stable and less biased than any single model.

This process is closely related to Random Forests, which also reduce variance by averaging many decorrelated trees. The main difference is that Random Forests use random subsets of predictors as well as bootstrap samples, while bagging only resamples the data.

Bagged-tree imputation therefore preserves relationships among variables while smoothing out noise and avoiding the distortions that mean or mode imputation can cause.

Before you decide how to impute, always explore where data are missing.

- Use functions such as

summary(),skimr::skim(), ornaniar::miss_var_summary()to inspect missing values in each column. - Identify which variables have the most missingness.

- Write two or three sentences: do you think the missingness is random or related to certain conditions (e.g., specific cities, traffic levels, or festivals)?

Let’s first make sure all variables are in the right format before checking for missingness:

glimpse(food)

Rows: 45,593

Columns: 27

$ ID <chr> "0xd936", "0xd681", "0x…

$ Delivery_person_ID <chr> "GOARES15DEL02", "GOARE…

$ Delivery_person_Age <dbl> 26, 38, 20, 39, 20, 33,…

$ Delivery_person_Ratings <dbl> 4.3, 4.9, 4.5, 4.7, 4.8…

$ Restaurant_latitude <dbl> 15.51315, 15.56129, 0.0…

$ Restaurant_longitude <dbl> 73.78346, 73.74948, 0.0…

$ Delivery_location_latitude <dbl> 15.56315, 15.60130, 0.0…

$ Delivery_location_longitude <dbl> 73.83346, 73.78948, 0.0…

$ Order_Date <date> 2022-02-11, 2022-02-11…

$ Time_Orderd <chr> "23:25:00", "13:35:00",…

$ Time_Order_picked <time> 23:35:00, 13:40:00, 21…

$ Weatherconditions <chr> "conditions Sandstorms"…

$ Road_traffic_density <chr> "Low", "High", "Jam", "…

$ Vehicle_condition <dbl> 0, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2,…

$ Type_of_order <chr> "Buffet", "Drinks", "Dr…

$ Type_of_vehicle <chr> "motorcycle", "scooter"…

$ multiple_deliveries <dbl> 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ Festival <chr> "No", "No", "No", "No",…

$ City <chr> "Urban", "Urban", "Metr…

$ `Time_taken(min)` <dbl> 21, 25, 27, 15, 25, 15,…

$ Order_Week <dbl> 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6,…

$ Season <chr> "Winter", "Winter", "Wi…

$ distance_km <dbl> 7.728973, 6.182554, 7.8…

$ Order_Hour <int> 23, 13, 21, 10, 18, 11,…

$ Pickup_Hour <int> 23, 13, 21, 10, 18, 11,…

$ Time_of_Day <chr> "Night", "Afternoon", "…

$ Order_Time_of_Day <chr> "Night", "Afternoon", "…It looks as if they’re mostly in the right format (including Time_taken(min) which is now numerical).

Now, let’s check for missingness

skimr::skim(food)

── Data Summary ────────────────────────

Values

Name food

Number of rows 45593

Number of columns 27

_______________________

Column type frequency:

character 12

Date 1

difftime 1

numeric 13

________________________

Group variables None

── Variable type: character ─────────────────────────────────

skim_variable n_missing complete_rate min max empty

1 ID 0 1 5 6 0

2 Delivery_person_ID 0 1 13 17 0

3 Time_Orderd 1731 0.962 8 8 0

4 Weatherconditions 0 1 14 21 0

5 Road_traffic_density 0 1 3 6 0

6 Type_of_order 0 1 4 6 0

7 Type_of_vehicle 0 1 7 16 0

8 Festival 0 1 2 3 0

9 City 0 1 3 13 0

10 Season 0 1 6 6 0

11 Time_of_Day 0 1 5 9 0

12 Order_Time_of_Day 1731 0.962 5 9 0

n_unique whitespace

1 45593 0

2 1320 0

3 176 0

4 7 0

5 5 0

6 4 0

7 4 0

8 3 0

9 4 0

10 2 0

11 4 0

12 4 0

── Variable type: Date ──────────────────────────────────────

skim_variable n_missing complete_rate min max

1 Order_Date 0 1 2022-02-11 2022-04-06

median n_unique

1 2022-03-15 44

── Variable type: difftime ──────────────────────────────────

skim_variable n_missing complete_rate min max

1 Time_Order_picked 0 1 0 secs 86100 secs

median n_unique

1 19:10 193

── Variable type: numeric ───────────────────────────────────

skim_variable n_missing complete_rate mean

1 Delivery_person_Age 1854 0.959 29.6

2 Delivery_person_Ratings 1908 0.958 4.63

3 Restaurant_latitude 0 1 17.0

4 Restaurant_longitude 0 1 70.2

5 Delivery_location_latitude 0 1 17.5

6 Delivery_location_longitude 0 1 70.8

7 Vehicle_condition 0 1 1.02

8 multiple_deliveries 993 0.978 0.745

9 Time_taken(min) 0 1 26.3

10 Order_Week 0 1 10.5

11 distance_km 0 1 99.4

12 Order_Hour 1731 0.962 17.4

13 Pickup_Hour 0 1 17.1

sd p0 p25 p50 p75 p100 hist

1 5.82 15 25 30 35 50 ▃▇▇▃▁

2 0.335 1 4.5 4.7 4.9 6 ▁▁▁▇▁

3 8.19 -30.9 12.9 18.5 22.7 30.9 ▁▁▁▆▇

4 22.9 -88.4 73.2 75.9 78.0 88.4 ▁▁▁▁▇

5 7.34 0.01 13.0 18.6 22.8 31.1 ▂▃▆▇▃

6 21.1 0.01 73.3 76.0 78.1 88.6 ▁▁▁▁▇

7 0.839 0 0 1 2 3 ▇▇▁▇▁

8 0.572 0 0 1 1 3 ▅▇▁▁▁

9 9.38 10 19 26 32 54 ▅▇▆▃▁

10 2.24 6 9 11 12 14 ▅▃▅▇▆

11 1101. 1.47 4.67 9.27 13.8 19715. ▇▁▁▁▁

12 4.82 0 15 19 21 23 ▁▁▂▃▇

13 5.33 0 14 19 21 23 ▁▁▂▃▇Most variables are complete. We have some missingness in Delivery_person_Age, Delivery_person_Ratings and multiple_deliveries (less than 5% of missing values). We also have some missingness in Time_Orderd and the derived Order_Hour and Order_Time_of_Day (less than 5% of missing values).

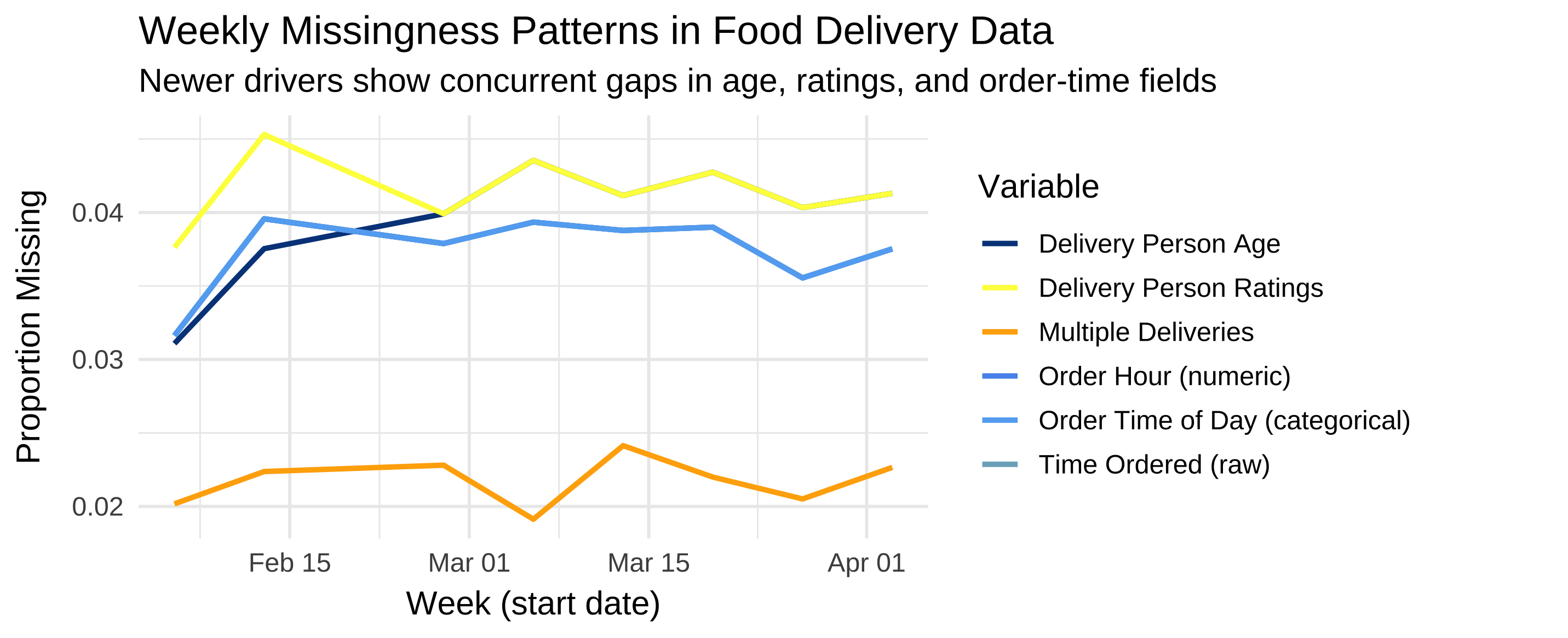

Let’s visualize how the proportion of missing values evolves weekly across all variables with known missingness.

# Summarize weekly missingness for all affected variables

df_summary <- food %>%

mutate(

week = floor_date(Order_Date, "week"),

age_miss = is.na(Delivery_person_Age),

rating_miss = is.na(Delivery_person_Ratings),

multi_miss = is.na(multiple_deliveries),

timeorder_miss = is.na(Time_Orderd),

orderhour_miss = is.na(Order_Hour),

ordertod_miss = is.na(Order_Time_of_Day)

) %>%

group_by(week) %>%

summarise(

prop_age_miss = mean(age_miss, na.rm = TRUE),

prop_rating_miss = mean(rating_miss, na.rm = TRUE),

prop_multi_miss = mean(multi_miss, na.rm = TRUE),

prop_timeorder_miss = mean(timeorder_miss, na.rm = TRUE),

prop_orderhour_miss = mean(orderhour_miss, na.rm = TRUE),

prop_ordertod_miss = mean(ordertod_miss, na.rm = TRUE),

.groups = "drop"

)

# Plot the weekly trends

df_summary %>%

ggplot(aes(x = week)) +

geom_line(aes(y = prop_age_miss, color = "Delivery Person Age"), linewidth = 1) +

geom_line(aes(y = prop_rating_miss, color = "Delivery Person Ratings"), linewidth = 1) +

geom_line(aes(y = prop_multi_miss, color = "Multiple Deliveries"), linewidth = 1) +

geom_line(aes(y = prop_timeorder_miss, color = "Time Ordered (raw)"), linewidth = 1) +

geom_line(aes(y = prop_orderhour_miss, color = "Order Hour (numeric)"), linewidth = 1) +

geom_line(aes(y = prop_ordertod_miss, color = "Order Time of Day (categorical)"), linewidth = 1) +

labs(

title = "Weekly Missingness Patterns in Food Delivery Data",

subtitle = "Newer drivers show concurrent gaps in age, ratings, and order-time fields",

y = "Proportion Missing",

x = "Week (start date)",

color = "Variable"

) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 13) +

scale_color_manual(values = c(

"Delivery Person Age" = "#044389",

"Delivery Person Ratings" = "#FCFF4B",

"Multiple Deliveries" = "#FFAD05",

"Time Ordered (raw)" = "#7CAFC4",

"Order Hour (numeric)" = "#5995ED",

"Order Time of Day (categorical)" = "#63ADF2"

))

5.6.2 🔎 Confirming overlaps among derived time features

The three order-time variables (Time_Orderd, Order_Hour, and Order_Time_of_Day) perfectly overlap in the plot because they share identical missingness patterns. You can verify this directly from df_summary:

df_summary %>%

summarise(

same_time_vs_hour = all.equal(prop_timeorder_miss, prop_orderhour_miss),

same_time_vs_tod = all.equal(prop_timeorder_miss, prop_ordertod_miss),

same_hour_vs_tod = all.equal(prop_orderhour_miss, prop_ordertod_miss)

)Output:

# A tibble: 1 × 3

same_time_vs_hour same_time_vs_tod same_hour_vs_tod

<lgl> <lgl> <lgl>

1 TRUE TRUE TRUE✅ This confirms that missing timestamps in Time_Orderd propagate exactly into Order_Hour and Order_Time_of_Day. In other words, these three lines are drawn on top of each other — the apparent “missing” lines are not lost, they’re simply perfectly coincident.

It’s normal to panic when you “lose” a line in a plot! But when multiple derived variables (like hour and day-part) are engineered from the same raw field, perfect overlap is actually a quality signal.

This overlap confirms that:

- The transformation pipeline is consistent — missing raw timestamps produce missing derived values.

- No artificial NAs or spurious imputations were introduced.

- Downstream models will treat these three features as jointly missing, avoiding hidden bias.

So rather than a visualization bug, this is a quick sanity check for preprocessing integrity.

5.7 🔍 Key Insights

5.7.2 2. Consistent propagation of timestamp missingness

The three time-related variables (Time_Orderd, Order_Hour, and Order_Time_of_Day) mirror each other exactly, meaning missingness was faithfully propagated. Each missing timestamp produces missing derived values — this is expected and correct behavior.

This kind of alignment ensures feature engineering does not inadvertently “repair” missing data, which would otherwise lead to inconsistent or misleading downstream features.

5.7.4 4. No Evidence of MNAR (Missing Not at Random)

We don’t see evidence that missingness depends on unobserved values — e.g., drivers with particularly low ratings being hidden or removed. The missingness correlates with observable temporal trends, not unmeasured traits.

This strongly supports a MAR (Missing At Random) process: missingness depends on observed data (such as time period or user onboarding), which we can explicitly model or handle with imputation methods like bagged trees.

5.8 🧠 Interpretation Summary

| Mechanism | Definition | Typical Clues | Evidence in This Dataset | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCAR (Missing Completely at Random) | Data are missing independently of both observed and unobserved values. | Flat, random missingness across time and variables; no correlation with external patterns. | ❌ Rejected — Missingness clearly increases over time and co-occurs across related variables (ratings, age, timestamps). | Not plausible; data collection changed systematically as new drivers entered. |

| MAR (Missing At Random) | Missingness depends on observed variables (e.g., time, onboarding stage). | Correlation between missingness and known, measurable processes. | ✅ Strongly supported — Missing values cluster in newer weeks, indicating dependency on time and user experience. | Plausible; can be safely imputed using predictors such as date, city, or delivery density. |

| MNAR (Missing Not At Random) | Missingness depends on unobserved or hidden values (e.g., low-rated drivers avoid self-reporting). | Diverging trends, unexplained gaps, or missingness aligned with extreme predictor values. | ⚠️ Unlikely — No divergence between variables, no hidden subgroups evident. | No direct evidence; could only be verified with external or longitudinal tracking data. |

5.8.1 ✅ Summary Takeaway

The consistent, time-linked pattern of missing data across multiple variables strongly supports a MAR mechanism. This means the missingness process is explainable and can be handled safely with supervised imputation techniques (like bagged-tree imputation), which leverage other predictors without biasing model estimates.

The observed structure — where age, ratings, and order-time variables become missing together — suggests a single, operational cause: driver onboarding or delayed data entry.

5.9 Build a regression recipe

You will now create a recipe that predicts Time_taken(min) from reasonable predictors. Do not copy a pre-written recipe here — write your own using the tidymodels recipes reference: https://recipes.tidymodels.org/reference/index.html

Your recipe should:

- Impute missing values with bagged trees (

step_impute_bag()). - Convert categorical predictors to dummy variables (

step_dummy()). - Normalize all numeric predictors (

step_normalize()). - Remove zero-variance predictors (

step_zv()).

5.9.1 ⚠️ Note on leakage

Always create and train your recipe after splitting the data. Defining the recipe is fine on the full dataset — it’s just a blueprint — but prep() must only ever be applied to the training data. tidymodels enforces this automatically when you put the recipe inside a workflow().

cross_rec <- recipe(`Time_taken(min)` ~ ., data = cross_train) |>

# Keep identifiers and raw geo/time fields OUT of the model:

update_role(

ID, Delivery_person_ID,

Order_Date, Order_Week, # keep for time-aware CV index, not as predictors

Time_Orderd, Time_Order_picked, # raw timestamps excluded, replaced by engineered features

Restaurant_latitude, Restaurant_longitude,

Delivery_location_latitude, Delivery_location_longitude, # summarized by distance_km

Season, # constant within one week → no info gain

new_role = "ID"

) |>

# Impute variables with known or propagated missingness using bagged trees

step_impute_bag(

all_of(c(

"Delivery_person_Ratings",

"Delivery_person_Age",

"multiple_deliveries",

"Order_Hour",

"Order_Time_of_Day"

)),

impute_with = imp_vars(all_predictors())

) |>

# Convert categorical predictors (City, Traffic, Festival, etc.) to dummies

step_dummy(all_nominal_predictors()) |>

# Remove zero-variance columns

step_zv(all_predictors()) |>

# Normalize numeric predictors (optional for trees, but good general hygiene)

step_normalize(all_numeric_predictors())5.9.2 🧭 1. update_role(...): protect non-predictors and avoid leakage

Some columns are essential for context and resampling, but would confuse or leak information if used as predictors:

| Variable(s) | Why not a predictor? | New role |

|---|---|---|

ID, Delivery_person_ID |

Pure identifiers. They’d let the model memorize individuals rather than generalize patterns. | "ID" |

Order_Date, Order_Week |

Encode when an order occurred, not why it took longer. Including them risks temporal leakage. We keep them only to define time-aware CV later. | "ID" |

Time_Orderd, Time_Order_picked |

Raw timestamps are granular, cyclical, and sparse; we replaced them with the interpretable day-part features Order_Time_of_Day and Time_of_Day. |

"ID" |

Restaurant_*, Delivery_location_* |

Separate lat/longs don’t express distance meaningfully and can mislead trees. We summarized them into distance_km using the Haversine formula. |

"ID" |

Season |

In the cross-sectional subset (one week), Season has only one level → no variation → no signal. We’ll re-enable seasonality in the longitudinal analysis. |

"ID" |

Why “update role” instead of dropping?

- We still need some fields for plots and time-aware resampling (e.g.,

Order_Date). - Keeping them documents the data lineage and makes the workflow reproducible and safe (no accidental reuse as predictors).

5.9.3 🧩 2. step_impute_bag(...): principled missing-data handling

- Bagged-tree imputation builds many small trees on bootstrap samples and averages their predictions for missing entries.

- This preserves nonlinear relationships and interactions better than mean/mode imputation and is conceptually close to tree ensembles like Random Forests (variance reduction by averaging de-correlated trees).

Derived variables like Order_Hour and Order_Time_of_Day can be very predictive, but they inherit missingness from raw timestamps such as Time_Orderd.

By imputing them directly (and not the raw timestamp), we ensure that:

- The model still benefits from time-of-day patterns,

- Missingness is handled coherently across related variables, and

- No data leakage occurs, since all imputations happen within training folds only.

This mirrors real-world modeling practice: engineer interpretable features → remove raw identifiers/timestamps → handle missingness at the feature level.

5.9.4 🧱 3. step_dummy(all_nominal_predictors()): turn categories into signals

- Models need numeric inputs. This step converts text categories — e.g.,

City,Road_traffic_density,Festival,Type_of_order,Order_Time_of_Day,Time_of_Day— into 0/1 dummy columns. - Example:

Time_of_Day = "Morning"becomesTime_of_Day_Morning = 1for that row and 0 otherwise.

5.9.5 📏 4. step_normalize(all_numeric_predictors()): consistent scales

- Some algorithms (KNN, SVM, penalized GLMs) are scale-sensitive.

- Normalizing now keeps the recipe model-agnostic so students can swap models later without rewriting preprocessing.

- Tree-based models are robust to scaling, so this step is harmless for LightGBM.

5.9.6 🧼 5. step_zv(all_predictors()): remove dead columns

- After dummying and imputing, some columns may have zero variance. This step drops them to keep the model matrix clean.

5.10 Choose and specify a regression model – LightGBM

We will use LightGBM, a modern gradient-boosted-tree algorithm that is very efficient on large tabular data.

Both LightGBM and XGBoost implement gradient boosting: a sequence of small trees is trained, each correcting residual errors from previous trees. The difference lies in how they grow trees and manage splits:

- XGBoost grows trees level-wise (balanced): it splits all leaves at one depth before going deeper. This produces symmetric trees and is often robust on small or moderately sized data.

- LightGBM grows trees leaf-wise: it always expands the single leaf that most reduces the loss, yielding deeper, targeted trees. Together with histogram-based binning of features, this makes LightGBM faster and often stronger on large, sparse, or high-cardinality data.

5.10.1 Example specification

lgb_mod <- boost_tree(

trees = 500,

learn_rate = 0.1,

tree_depth = 6,

loss_reduction = 0.0,

min_n = 2

) |>

set_engine("lightgbm") |>

set_mode("regression")5.10.2 Common LightGBM tuning parameters

| Parameter | What it controls | Intuition |

|---|---|---|

trees |

total number of trees | more trees can capture more structure but risk overfitting unless learn_rate is small |

learn_rate |

step size for each tree’s contribution | small = slower but safer learning; large = faster but riskier |

tree_depth |

maximum depth of a single tree | deeper trees capture complex interactions but can overfit |

loss_reduction |

minimum loss reduction to make a split | larger values prune weak splits and simplify trees |

min_n |

minimum observations in a leaf | prevents tiny leaves that memorize noise |

mtry |

number of predictors sampled at each split | adds randomness, reduces correlation among trees |

When might you prefer XGBoost? On smaller datasets, when stability and interpretability matter. When might you prefer LightGBM? For speed on larger tables, many categorical dummies, or limited tuning time.

5.11 Combine recipe and model inside a workflow

Once your recipe and model specification are ready, combine them with workflow() so preprocessing and modeling stay linked. Workflows automatically apply the recipe before fitting or predicting.

reg_wf <- workflow() |>

add_recipe(cross_rec) |>

add_model(lgb_mod)5.12 Evaluate the cross-sectional model

Fit your workflow on the training set and evaluate predictions on the test set.

Use regression metrics such as RMSE, MAE, and R².

Compute and report these metrics for your model.

How accurate is the model on unseen data?

Does it tend to over- or under-predict delivery time?

cross_fit <- reg_wf |> fit(cross_train)

cross_preds <- predict(cross_fit, cross_test) |>

bind_cols(cross_test |> select(`Time_taken(min)`))

metric_set(rmse, mae, rsq)(

cross_preds,

truth = `Time_taken(min)`,

estimate = .pred

)Output

# A tibble: 3 × 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 rmse standard 4.31

2 mae standard 3.43

3 rsq standard 0.771These results tell us that our model performs quite well for a single operational week — but with some natural limitations.

5.12.1 1️⃣ Accuracy of time predictions

An RMSE of about 4.3 minutes means that, on average, predicted delivery times are within roughly ±4–5 minutes of the actual values. Given that most deliveries take between 10 and 50 minutes, this error margin represents roughly 10–15% of a typical delivery duration — quite precise for a real-world logistics process.

The MAE of 3.4 minutes confirms that the typical prediction error is small and that the few large deviations (perhaps during peak traffic or bad weather) are not overwhelming. The gap between RMSE and MAE is modest, suggesting the model performs consistently across most deliveries, with only limited outlier impact.

5.12.2 2️⃣ How much variation the model explains

The R² value of 0.77 means that around three-quarters of all variation in delivery times can be explained by the predictors included — variables such as:

- Distance, which captures spatial effort,

- Traffic density, which captures congestion, and

- Weather conditions, which influence travel safety and speed.

The remaining 23% of unexplained variation likely stems from unobserved or inherently random factors:

- restaurant preparation times,

- small detours or parking delays,

- driver skill differences, or

- special events not recorded in the dataset.

5.12.3 3️⃣ What this means in practice

For a restaurant manager or delivery company, this level of accuracy could already be useful:

- Predicting when to alert customers (“your delivery will arrive in about 25 minutes”)

- Planning driver assignments or restocking intervals

- Identifying potential bottlenecks when actual times systematically exceed predictions

5.12.4 4️⃣ Important caveat: one week ≠ the whole story

Because this is a cross-sectional snapshot (one week only), the model hasn’t been tested on how patterns evolve over time. For example:

- Festivals or new delivery routes might change the relationships between predictors and time,

- Weather patterns might shift from winter to spring,

- Or new drivers might behave differently from earlier ones.

Therefore, the next step — time-aware cross-validation — will tell us whether this model remains reliable when predicting future weeks rather than just this one.

Numerical metrics tell part of the story — but to see how your model behaves, you need to inspect residuals (the differences between actual and predicted delivery times).

Try plotting:

Predicted vs. actual delivery times

→ Are most points near the diagonal (perfect predictions)?

→ Do errors grow with longer delivery times?Residuals vs. predicted values

→ Are residuals centered around zero (no systematic bias)?

→ Do you see patterns that might suggest missing predictors?Residuals by time of day

→ Are certain times (e.g., evening rush hours) consistently over- or under-predicted?

Write a short paragraph summarizing what you notice.

Does the model perform equally well for all deliveries, or does it struggle under specific conditions?

5.12.5 Cross-validation on the cross-sectional data

So far, you evaluated the model with a single train/test split. In a cross-sectional setting (no time ordering), it is common to use k-fold cross-validation, which splits the training data into k random folds, training on k – 1 folds and validating on the remaining fold in turn. This yields a more robust estimate of performance stability.

set.seed(42)

cv_cross <- vfold_cv(cross_train, v = 5)

cross_cv_res <- fit_resamples(

reg_wf,

resamples = cv_cross,

metrics = metric_set(rmse, mae, rsq),

control = control_resamples(save_pred = TRUE)

)

collect_metrics(cross_cv_res)Run a 5-fold cross-validation on the cross-sectional training data. Compare the average RMSE and R² to those from the single test-set evaluation. Are they similar? Which estimate do you trust more?

Output

# A tibble: 3 × 6

.metric .estimator mean n std_err .config

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <chr>

1 mae standard 3.50 5 0.0235 pre0_mod0_post0

2 rmse standard 4.51 5 0.0327 pre0_mod0_post0

3 rsq standard 0.756 5 0.00324 pre0_mod0_post0Interpretation:

The CV metrics are close to the single test-set values, confirming consistent performance. Cross-validation gives a more stable estimate because it reuses the data more efficiently.

5.13 Time-aware validation with sliding_period()

In time-dependent data, future information must not influence the model’s training. To mimic real-world deployment, we roll forward through time: train on past weeks, validate on the next week(s).

food <- food |>

mutate(

Season = case_when(

Order_Week %in% 1:13 ~ "Winter",

Order_Week %in% 14:26 ~ "Spring",

Order_Week %in% 27:39 ~ "Summer",

Order_Week %in% 40:52 ~ "Autumn",

TRUE ~ NA_character_

),

Season = factor(Season, levels = c("Winter", "Spring", "Summer", "Autumn"))

) #Season is converted to factor so that it's correctly handled by steps that require factor variables e.g step_novel() or step_dummy()

# create a chronological split first

set.seed(42)

long_split <- initial_time_split(food, prop = 0.8)

long_train <- training(long_split)

long_test <- testing(long_split)

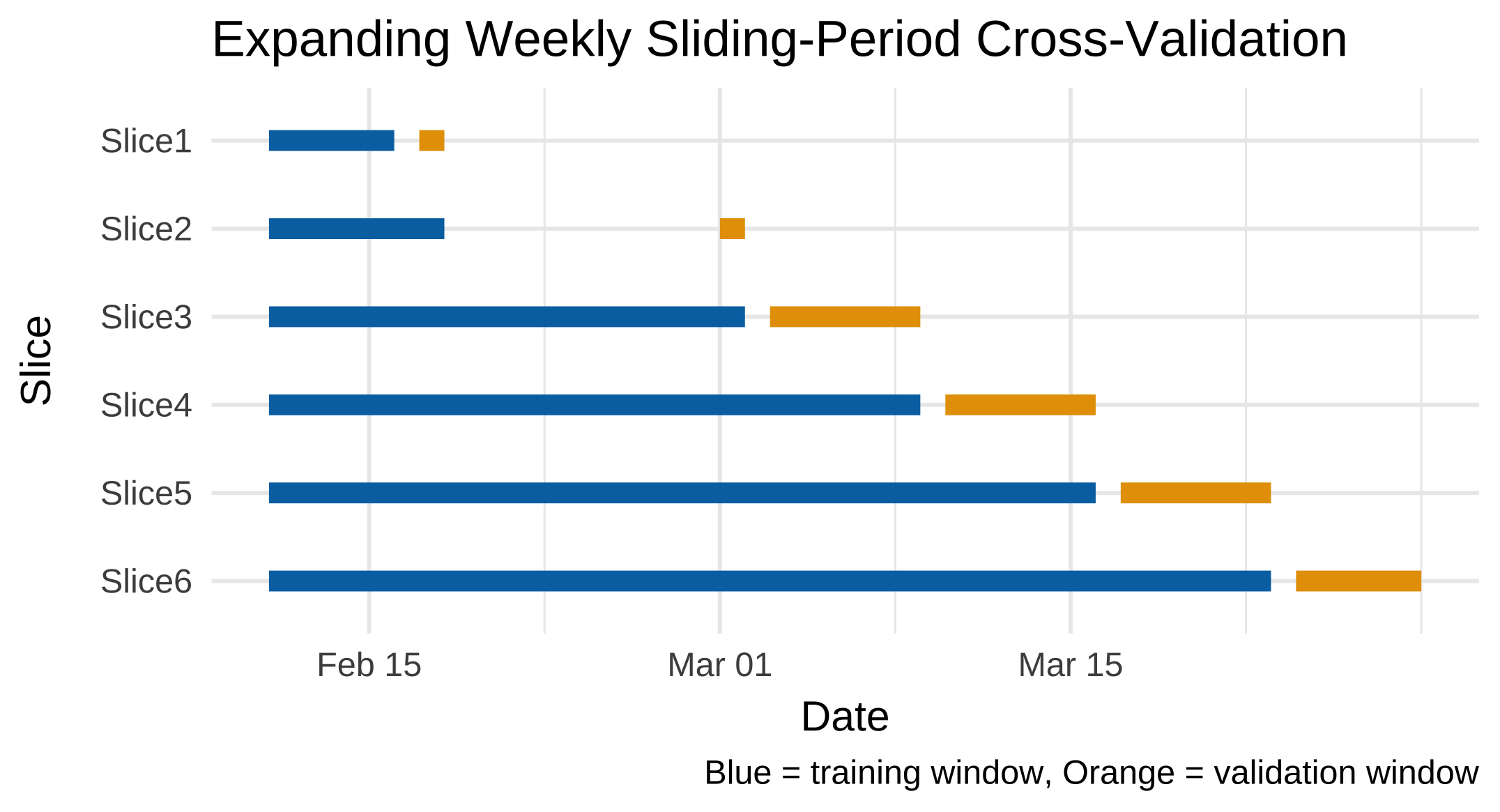

cv_long <- sliding_period(

data = long_train, # your longitudinal training data (not the full dataset!)

index = Order_Date,

period = "week",

lookback = Inf, # how many past weeks form the training window

assess_stop = 1 # how many future weeks form the validation window

)Never define cross-validation folds on the entire dataset. If you did, the model could “peek” at future data while training, inflating performance. Instead, use only the training portion of your longitudinal split—here called long_train.

5.13.1 How sliding_period() works

sliding_period() creates a sequence of rolling resamples ordered by the variable given in index. Here, the index is Order_Date, which is of class Date. Because it understands the class of this variable, rsample can interpret the keyword period = "week" as:

“Use the calendar weeks implied by the

Datevariable to move the window forward one week at a time.”

Internally, it uses date arithmetic (floor_date() and ceiling_date() logic) to determine where each new week starts and stops. If you had specified period = "day" or period = "month", it would instead roll forward daily or monthly. Thus, period defines the temporal granularity of each split, and index provides the timeline to follow.

Let’s try and have a look at which dates the sliding_period() cross-validation folds correspond to:

cv_long_summary <- cv_long %>%

mutate(

train_start = map(splits, ~ min(analysis(.x)$Order_Date)),

train_end = map(splits, ~ max(analysis(.x)$Order_Date)),

val_start = map(splits, ~ min(assessment(.x)$Order_Date)),

val_end = map(splits, ~ max(assessment(.x)$Order_Date))

) %>%

tidyr::unnest(c(train_start, train_end, val_start, val_end)) %>%

select(id, train_start, train_end, val_start, val_end)

cv_long_summary# A tibble: 6 × 5

id train_start train_end val_start val_end

<chr> <date> <date> <date> <date>

1 Slice1 2022-02-11 2022-02-16 2022-02-17 2022-02-18

2 Slice2 2022-02-11 2022-02-18 2022-03-01 2022-03-02

3 Slice3 2022-02-11 2022-03-02 2022-03-03 2022-03-09

4 Slice4 2022-02-11 2022-03-09 2022-03-10 2022-03-16

5 Slice5 2022-02-11 2022-03-16 2022-03-17 2022-03-23

6 Slice6 2022-02-11 2022-03-23 2022-03-24 2022-03-29If you want to have a look at which weeks these folds correspond to instead:

cv_long_summary_weeks <- cv_long %>%

mutate(

train_start_wk = map_int(splits, ~ isoweek(min(analysis(.x)$Order_Date))),

train_end_wk = map_int(splits, ~ isoweek(max(analysis(.x)$Order_Date))),

val_start_wk = map_int(splits, ~ isoweek(min(assessment(.x)$Order_Date))),

val_end_wk = map_int(splits, ~ isoweek(max(assessment(.x)$Order_Date)))

) %>%

select(id, train_start_wk, train_end_wk, val_start_wk, val_end_wk)

cv_long_summary_weeks# A tibble: 6 × 5

id train_start_wk train_end_wk val_start_wk val_end_wk

<chr> <int> <int> <int> <int>

1 Slice1 6 7 7 7

2 Slice2 6 7 9 9

3 Slice3 6 9 9 10

4 Slice4 6 10 10 11

5 Slice5 6 11 11 12

6 Slice6 6 12 12 13And if you want to visualise the folds:

cv_long_summary %>%

mutate(id = factor(id, levels = rev(id))) %>% # reverse for readability

ggplot() +

geom_segment(aes(x = train_start, xend = train_end, y = id, yend = id),

color = "#0072B2", linewidth = 3) +

geom_segment(aes(x = val_start, xend = val_end, y = id, yend = id),

color = "#E69F00", linewidth = 3) +

labs(

title = "Expanding Weekly Sliding-Period Cross-Validation",

x = "Date", y = "Slice",

caption = "Blue = training window, Orange = validation window"

) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 13)

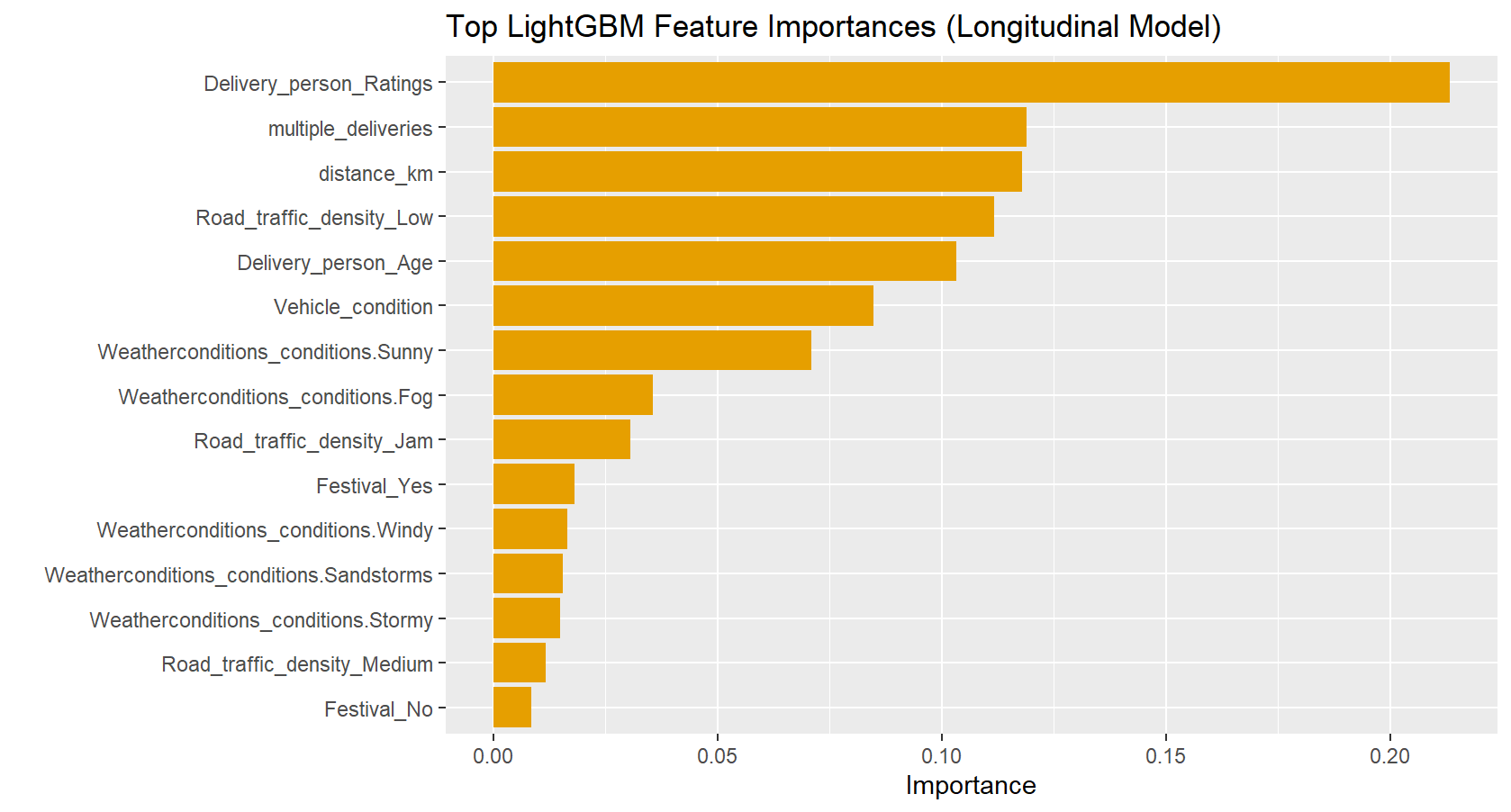

5.14 Recipe, workflow, and modeling for longitudinal validation

Repeat the full process—recipe, model, and workflow—on the longitudinal setup. Then train and evaluate the model using the time-aware resamples created above.

Use fit_resamples() to fit your LightGBM workflow with cv_long. Collect metrics (rmse, mae, rsq) and summarize them.

long_rec <- recipe(`Time_taken(min)` ~ ., data = long_train) |>

# Exclude pure identifiers and raw time/geo columns from modeling

update_role(

ID, Delivery_person_ID,

Order_Date, Order_Week, # kept for time-aware resampling but not for prediction

Time_Orderd, Time_Order_picked, # raw timestamps replaced by engineered features

Restaurant_latitude, Restaurant_longitude,

Delivery_location_latitude, Delivery_location_longitude,

new_role = "ID"

) |>

# Impute missing values using bagged trees

step_impute_bag(

all_of(c(

"Delivery_person_Ratings",

"Delivery_person_Age",

"multiple_deliveries",

"Order_Hour",

"Order_Time_of_Day"

)),

impute_with = imp_vars(all_predictors())

) |>

# Handle unseen categorical levels (e.g., new "Spring" season appearing post-training)

step_novel(all_nominal_predictors()) |>

# Convert categorical predictors (Season, City, Road_traffic_density, Festival, etc.)

step_dummy(all_nominal_predictors()) |>

# Remove zero-variance columns

step_zv(all_predictors()) |>

# Normalize numeric predictors (safe default even for trees)

step_normalize(all_numeric_predictors())

long_wf <- workflow() |>

add_recipe(long_rec) |>

add_model(lgb_mod)

set.seed(42)

long_res <- fit_resamples(

long_wf,

resamples = cv_long,

metrics = metric_set(rmse, mae, rsq),

control = control_resamples(save_pred = TRUE)

)

collect_metrics(long_res)5.14.1 🧭 Explanation

5.14.1.1 1. Roles updated like the cross-sectional recipe

We exclude identifiers and raw geographic/time fields that could cause leakage or confuse the model. Unlike the cross-sectional version, we keep Season as a predictor now, because time variation matters in longitudinal modeling.

| Variable(s) | Role | Why |

|---|---|---|

ID, Delivery_person_ID |

"ID" |

Unique identifiers; would lead to memorization if used as predictors. |

Order_Date, Order_Week |

"ID" |

Used only as the time index for resampling, not for prediction. |

Time_Orderd, Time_Order_picked |

"ID" |

Replaced by derived variables (Order_Hour, Order_Time_of_Day, etc.) that capture interpretable cyclic patterns. |

Restaurant_latitude/longitude, Delivery_location_latitude/longitude |

"ID" |

Represented more meaningfully by the engineered feature distance_km. |

Season remains a predictor because it provides temporal context (seasonal traffic, weather, demand).

5.14.1.2 2. Imputation covers all known-missing columns

We explicitly include all variables where we’ve observed missingness:

Delivery_person_RatingsDelivery_person_Agemultiple_deliveriesOrder_HourOrder_Time_of_Day

This ensures consistent treatment between short-term (cross-sectional) and longitudinal contexts.

5.14.1.3 3. step_novel() — essential for unseen levels

Because all training data belong to Winter but testing includes Spring deliveries, step_novel() is added before dummy encoding to handle new categorical levels gracefully.

Without it, bake() would fail when encountering "Spring", since the recipe prepared only "Winter". This step mimics real-world temporal generalization — when a model trained in one period faces new categories later.

5.14.1.4 4. Normalization kept for generality

Although tree-based models (like LightGBM) don’t require normalized inputs, this normalization step helps if you later try linear, ElasticNet, KNN or SVM models.

Using nearly identical recipes for cross-sectional and longitudinal designs:

- Makes comparisons fair — differences in results reflect temporal validation, not preprocessing.

- Ensures data preparation is stable across experiments (so that performance differences can be ascribed to modeling not data preparation!).

- Simplifies later workflow assembly and hyperparameter tuning code.

Because our longitudinal training data only include Winter deliveries, but the test data add Spring ones, the model will face an unseen category at prediction time.

step_novel() ensures the recipe anticipates new levels like "Spring" and assigns them to a safe “novel” category during encoding, avoiding model failure.

This is a real-world example of temporal covariate shift — new conditions (e.g., new seasons, new cities, or new delivery modes) appearing after training.

Output

# A tibble: 3 × 6

.metric .estimator mean n std_err .config

<chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <chr>

1 mae standard 3.30 6 0.0634 pre0_mod0_post0

2 rmse standard 4.18 6 0.0813 pre0_mod0_post0

3 rsq standard 0.797 6 0.00948 pre0_mod0_post0Note: Expect slightly different numbers than the cross-sectional test split because (a) folds change over weeks, and (b) training windows grow over time.

5.15 Challenge: comparing designs

Compare your cross-sectional and longitudinal results.

- Are the results directly comparable? Why or why not?

- Which design better represents real-world performance, and why?

- How does time-aware validation change your interpretation of model quality?

5.15.1 🔍 Summary of results

| Design | RMSE ↓ | MAE ↓ | R² ↑ | Resampling | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional (CV) | 4.51 | 3.50 | 0.756 | Random folds within one week | Easier problem — limited temporal drift |

| Longitudinal (rolling CV) | 4.18 | 3.30 | 0.797 | Past→Future expanding windows | Harder setup but more realistic |

5.15.2 🧭 Interpretation

1. Are the results directly comparable?

Not entirely.

The cross-sectional design samples from a single busy week with random splits, while the longitudinal setup uses sequential, expanding windows across multiple weeks.

Each fold in the longitudinal setup reflects a different temporal context — so its performance better represents how a deployed model will behave as conditions evolve.

Moreover, the two designs differ in data distribution and training volume: the cross-sectional model sees only one high-stress operational regime (e.g., consistent traffic, weather, and driver behavior), whereas the longitudinal model trains on an accumulating history of weeks with varying conditions (festivals, weather shifts, new drivers). This means the longitudinal model benefits from more diverse and abundant training data, which can improve generalization. Because of these differences—distributional shift, temporal structure, and data volume—the metrics are not strictly comparable; they answer subtly different questions about model behavior.

2. Which design better represents real-world deployment?

The time-aware longitudinal design does.

In real applications, we predict future deliveries using patterns learned from the past — never mixing the two.

Its slightly lower RMSE and MAE combined with higher R² suggest that the model generalizes robustly across time, not just within one week’s context.

Critically, this design respects temporal causality: no future information leaks into training. Random cross-sectional CV violates this principle by shuffling observations across time, which inflates performance estimates and creates a false sense of reliability. The longitudinal approach, by contrast, simulates real forecasting conditions—making its results not only more realistic but also more trustworthy for operational planning. The larger standard errors in the longitudinal metrics (e.g., RMSE std_err = 0.081 vs. 0.033) further reflect the natural variability in delivery dynamics over time—a feature, not a bug, as it honestly quantifies uncertainty in a changing environment.

3. Why did the longitudinal model slightly outperform the cross-sectional one?

A few plausible reasons:

- The longitudinal design uses more total training data (cumulative weeks), improving stability.

- Seasonal/contextual predictors (e.g., traffic density, weather) add meaningful temporal variation.

- The model may have learned smoother relationships by observing multiple weekly contexts.

Importantly, although time-aware validation is typically more challenging, here the benefit of richer, more varied training data appears to outweigh the difficulty of forecasting the future—leading to better overall performance.

4. Key takeaway

If a model performs consistently under time-aware validation, it is more trustworthy for forecasting tasks, even if cross-sectional metrics look similar or slightly better.

For any prediction task involving time, time-aware validation isn’t just preferable—it’s essential to avoid overestimating real-world performance and deploying models that fail when conditions evolve.

In this tutorial, we compared cross-validation results (rather than test-set results) for a key reason:

Cross-validation gives a distribution of model performance across multiple folds (or time windows), revealing stability and temporal robustness. The test set, by contrast, is a single split — useful for final confirmation, but not sufficient to judge generalization on its own.

In time-aware setups, each resample already acts as a mini test, predicting unseen weeks from prior ones. Hence, cross-validation metrics are the most informative comparison across designs:

- Cross-sectional CV: tests within one busy week (random 80/20)

- Time-aware CV: tests repeatedly across future weeks (expanding window)

Later, we’ll complement these with final test-set results when comparing LightGBM and ElasticNet directly.

5.16 🧗 Challenge: try another model

Repeat the workflow using a different algorithm of your choice (for example, Elastic-Net, SVM, or KNN). Do not copy specifications here — consult lectures, 📚labs W02–W05, and the reading week homework for syntax, recommended preprocessing, and tuning guidance.

Evaluate the alternative model on both cross-sectional and time-aware folds and compare results.

- Which model generalized best over time?

- Did any model overfit when using random folds but degrade under time-aware validation?

- Which preprocessing steps (such as normalization) were essential for your chosen model, and why?

- Would your preferred model still perform well if new conditions appeared (e.g., “Summer” deliveries or new cities)?

5.16.1 💡 Example models (and specification)

| Model | Formula | Engine | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic-Net | linear_reg(penalty = tune(), mixture = tune()) |

"glmnet" |

Requires normalized inputs; interpretable; may underfit nonlinear effects. |

| SVM (RBF) | svm_rbf(cost = tune(), rbf_sigma = tune()) |

"kernlab" |

Handles nonlinearities; benefits from scaling; can be slower on large data. |

| KNN | nearest_neighbor(neighbors = tune()) |

"kknn" |

Very sensitive to normalization; local patterns may not generalize well over time. |

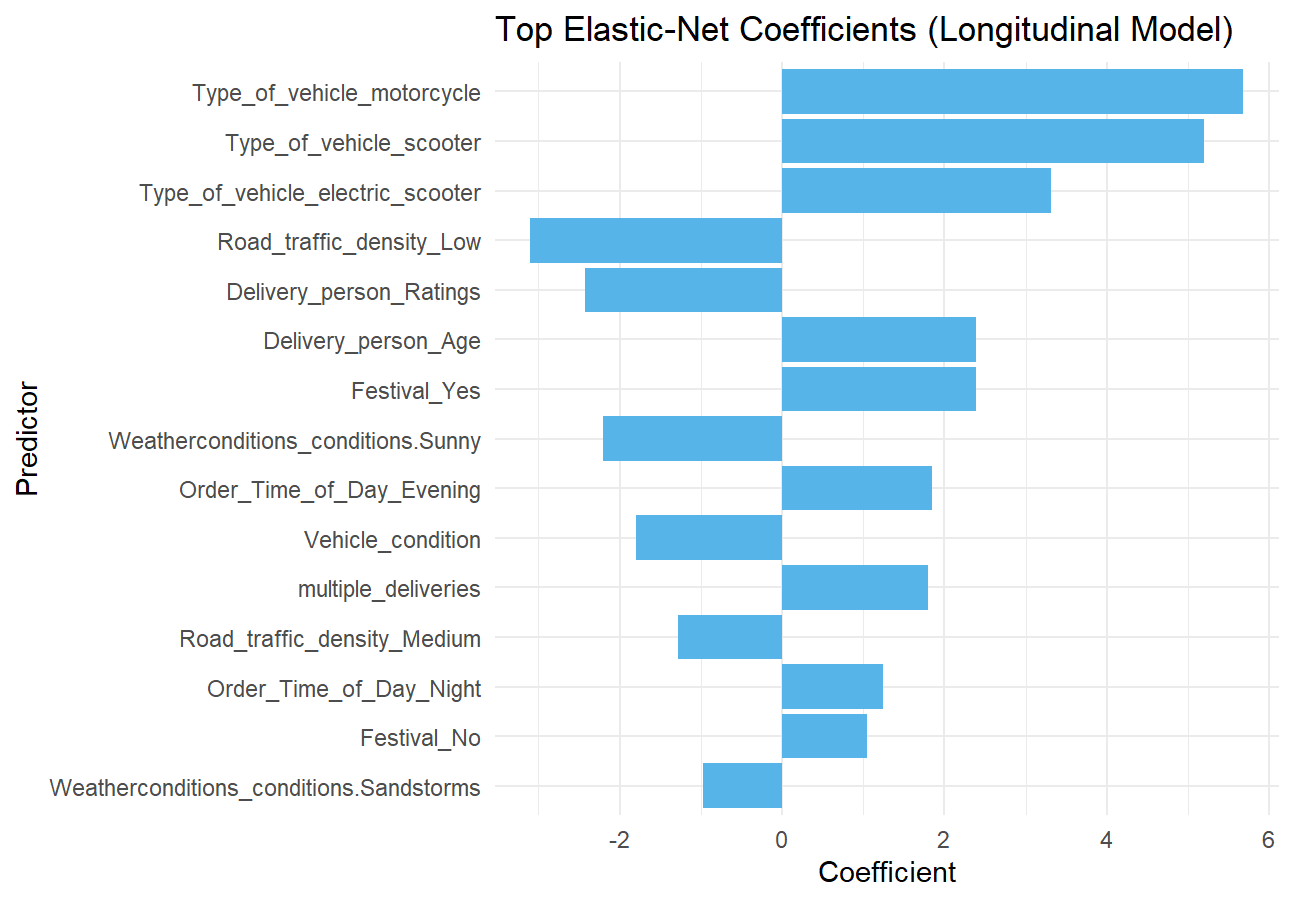

In what follows, we’ll focus on ElasticNet to contrast a linear, interpretable model with the nonlinear, high-performance LightGBM.

5.17 🔁 Elastic Net regression – cross-sectional design

# Elastic Net specification

enet_mod <- linear_reg(

penalty = tune(), # overall regularization strength (λ)

mixture = tune() # 0 = ridge, 1 = lasso, in-between = elastic

) |>

set_engine("glmnet")

# Use the same recipe as the cross-sectional model

cross_enet_rec <- cross_rec

# Combine into workflow

cross_enet_wf <- workflow() |>

add_recipe(cross_enet_rec) |>

add_model(enet_mod)

# Define a grid of λ and α values

enet_grid <- grid_regular(

penalty(range = c(-3, 0)), # λ ≈ 10⁻³ → 1

mixture(range = c(0, 1)), # ridge → lasso

levels = 6

)

set.seed(42)

cross_enet_res <- tune_grid(

cross_enet_wf,

resamples = cv_cross,

grid = enet_grid,

metrics = metric_set(rmse, mae, rsq),

control = control_grid(save_pred = TRUE)

)

print(collect_metrics(cross_enet_res),n=110)# A tibble: 108 × 8

penalty mixture .metric .estimator mean n std_err .config

<dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <chr>

1 0.001 0 mae standard 4.85 5 0.0381 pre0_mod01_post0

2 0.001 0 rmse standard 6.15 5 0.0258 pre0_mod01_post0

3 0.001 0 rsq standard 0.547 5 0.00277 pre0_mod01_post0

4 0.001 0.2 mae standard 4.85 5 0.0363 pre0_mod02_post0

5 0.001 0.2 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0229 pre0_mod02_post0

6 0.001 0.2 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00267 pre0_mod02_post0

7 0.001 0.4 mae standard 4.85 5 0.0363 pre0_mod03_post0

8 0.001 0.4 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0229 pre0_mod03_post0

9 0.001 0.4 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00267 pre0_mod03_post0

10 0.001 0.6 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0367 pre0_mod04_post0

11 0.001 0.6 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0231 pre0_mod04_post0

12 0.001 0.6 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00269 pre0_mod04_post0

13 0.001 0.8 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0368 pre0_mod05_post0

14 0.001 0.8 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0232 pre0_mod05_post0

15 0.001 0.8 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00270 pre0_mod05_post0

16 0.001 1 mae standard 4.85 5 0.0364 pre0_mod06_post0

17 0.001 1 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0229 pre0_mod06_post0

18 0.001 1 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00267 pre0_mod06_post0

19 0.00398 0 mae standard 4.85 5 0.0381 pre0_mod07_post0

20 0.00398 0 rmse standard 6.15 5 0.0258 pre0_mod07_post0

21 0.00398 0 rsq standard 0.547 5 0.00277 pre0_mod07_post0

22 0.00398 0.2 mae standard 4.85 5 0.0363 pre0_mod08_post0

23 0.00398 0.2 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0229 pre0_mod08_post0

24 0.00398 0.2 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00267 pre0_mod08_post0

25 0.00398 0.4 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0362 pre0_mod09_post0

26 0.00398 0.4 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0230 pre0_mod09_post0

27 0.00398 0.4 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00265 pre0_mod09_post0

28 0.00398 0.6 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0366 pre0_mod10_post0

29 0.00398 0.6 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0233 pre0_mod10_post0

30 0.00398 0.6 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00266 pre0_mod10_post0

31 0.00398 0.8 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0367 pre0_mod11_post0

32 0.00398 0.8 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0235 pre0_mod11_post0

33 0.00398 0.8 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00266 pre0_mod11_post0

34 0.00398 1 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0363 pre0_mod12_post0

35 0.00398 1 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0234 pre0_mod12_post0

36 0.00398 1 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00262 pre0_mod12_post0

37 0.0158 0 mae standard 4.85 5 0.0381 pre0_mod13_post0

38 0.0158 0 rmse standard 6.15 5 0.0258 pre0_mod13_post0

39 0.0158 0 rsq standard 0.547 5 0.00277 pre0_mod13_post0

40 0.0158 0.2 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0365 pre0_mod14_post0

41 0.0158 0.2 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0236 pre0_mod14_post0

42 0.0158 0.2 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00262 pre0_mod14_post0

43 0.0158 0.4 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0369 pre0_mod15_post0

44 0.0158 0.4 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0242 pre0_mod15_post0

45 0.0158 0.4 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00265 pre0_mod15_post0

46 0.0158 0.6 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0371 pre0_mod16_post0

47 0.0158 0.6 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0242 pre0_mod16_post0

48 0.0158 0.6 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00264 pre0_mod16_post0

49 0.0158 0.8 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0371 pre0_mod17_post0

50 0.0158 0.8 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0242 pre0_mod17_post0

51 0.0158 0.8 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00265 pre0_mod17_post0

52 0.0158 1 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0369 pre0_mod18_post0

53 0.0158 1 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0242 pre0_mod18_post0

54 0.0158 1 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00264 pre0_mod18_post0

55 0.0631 0 mae standard 4.85 5 0.0381 pre0_mod19_post0

56 0.0631 0 rmse standard 6.15 5 0.0258 pre0_mod19_post0

57 0.0631 0 rsq standard 0.547 5 0.00277 pre0_mod19_post0

58 0.0631 0.2 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0372 pre0_mod20_post0

59 0.0631 0.2 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0244 pre0_mod20_post0

60 0.0631 0.2 rsq standard 0.548 5 0.00267 pre0_mod20_post0

61 0.0631 0.4 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0362 pre0_mod21_post0

62 0.0631 0.4 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0245 pre0_mod21_post0

63 0.0631 0.4 rsq standard 0.547 5 0.00262 pre0_mod21_post0

64 0.0631 0.6 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0356 pre0_mod22_post0

65 0.0631 0.6 rmse standard 6.14 5 0.0245 pre0_mod22_post0

66 0.0631 0.6 rsq standard 0.547 5 0.00255 pre0_mod22_post0

67 0.0631 0.8 mae standard 4.84 5 0.0349 pre0_mod23_post0

68 0.0631 0.8 rmse standard 6.15 5 0.0245 pre0_mod23_post0

69 0.0631 0.8 rsq standard 0.546 5 0.00247 pre0_mod23_post0

70 0.0631 1 mae standard 4.85 5 0.0340 pre0_mod24_post0

71 0.0631 1 rmse standard 6.15 5 0.0244 pre0_mod24_post0

72 0.0631 1 rsq standard 0.546 5 0.00237 pre0_mod24_post0

73 0.251 0 mae standard 4.85 5 0.0381 pre0_mod25_post0

74 0.251 0 rmse standard 6.15 5 0.0258 pre0_mod25_post0

75 0.251 0 rsq standard 0.547 5 0.00277 pre0_mod25_post0

76 0.251 0.2 mae standard 4.86 5 0.0346 pre0_mod26_post0

77 0.251 0.2 rmse standard 6.16 5 0.0248 pre0_mod26_post0

78 0.251 0.2 rsq standard 0.545 5 0.00246 pre0_mod26_post0

79 0.251 0.4 mae standard 4.88 5 0.0335 pre0_mod27_post0

80 0.251 0.4 rmse standard 6.18 5 0.0247 pre0_mod27_post0

81 0.251 0.4 rsq standard 0.542 5 0.00209 pre0_mod27_post0

82 0.251 0.6 mae standard 4.90 5 0.0329 pre0_mod28_post0

83 0.251 0.6 rmse standard 6.21 5 0.0254 pre0_mod28_post0

84 0.251 0.6 rsq standard 0.538 5 0.00200 pre0_mod28_post0

85 0.251 0.8 mae standard 4.91 5 0.0339 pre0_mod29_post0

86 0.251 0.8 rmse standard 6.24 5 0.0264 pre0_mod29_post0

87 0.251 0.8 rsq standard 0.536 5 0.00180 pre0_mod29_post0

88 0.251 1 mae standard 4.93 5 0.0344 pre0_mod30_post0

89 0.251 1 rmse standard 6.26 5 0.0276 pre0_mod30_post0

90 0.251 1 rsq standard 0.534 5 0.00170 pre0_mod30_post0

91 1 0 mae standard 4.88 5 0.0389 pre0_mod31_post0

92 1 0 rmse standard 6.18 5 0.0276 pre0_mod31_post0

93 1 0 rsq standard 0.543 5 0.00282 pre0_mod31_post0

94 1 0.2 mae standard 4.95 5 0.0374 pre0_mod32_post0

95 1 0.2 rmse standard 6.27 5 0.0286 pre0_mod32_post0

96 1 0.2 rsq standard 0.535 5 0.00194 pre0_mod32_post0

97 1 0.4 mae standard 5.02 5 0.0393 pre0_mod33_post0

98 1 0.4 rmse standard 6.36 5 0.0343 pre0_mod33_post0

99 1 0.4 rsq standard 0.531 5 0.00107 pre0_mod33_post0

100 1 0.6 mae standard 5.12 5 0.0423 pre0_mod34_post0

101 1 0.6 rmse standard 6.49 5 0.0401 pre0_mod34_post0

102 1 0.6 rsq standard 0.524 5 0.000917 pre0_mod34_post0

103 1 0.8 mae standard 5.24 5 0.0428 pre0_mod35_post0

104 1 0.8 rmse standard 6.63 5 0.0441 pre0_mod35_post0

105 1 0.8 rsq standard 0.516 5 0.00127 pre0_mod35_post0

106 1 1 mae standard 5.39 5 0.0403 pre0_mod36_post0

107 1 1 rmse standard 6.79 5 0.0447 pre0_mod36_post0

108 1 1 rsq standard 0.508 5 0.00157 pre0_mod36_post0The Elastic Net grid search produced remarkably stable results across all combinations of the penalty (λ) and mixture (α) parameters. Neither stronger regularization nor changes in the ridge–lasso balance materially affected model performance:

| Metric | Mean ± SE | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 6.14 ± 0.03 | Prediction error varied by less than 0.05 minutes across the grid → very flat error surface. |

| MAE | 4.85 ± 0.04 | Small, stable deviations across folds → regularization strength has minimal effect. |

| R² | 0.55 ± 0.01 | Indicates that only about half of the variation in delivery time is captured by a linear additive structure. |

Interpretation:

This tuning profile suggests that the Elastic Net model is insensitive to the regularization path—a hallmark of data where predictors are moderately collinear but relationships remain roughly linear. The flat performance landscape implies that most signal is already being captured by the baseline linear combination of features, with no further benefit from shrinking or sparsifying coefficients.

However, the limited (R^2 ) also reveals that a substantial nonlinear or interaction component remains unexplained. These are precisely the kinds of effects that tree-based ensembles (like LightGBM) can exploit—non-additive interactions between distance, traffic density, and time of day that a linear model cannot represent.

Takeaway: Elastic Net yields a stable but constrained fit—ideal for interpretability and diagnostic insight, but not for squeezing out the last increments of predictive accuracy. Its near-ridge behaviour (best λ ≈ 0.001, α ≈ 0.4–0.6) further confirms that the model benefits from mild shrinkage rather than sparsity.

5.18 ⏳ Elastic Net regression – longitudinal (time-aware) design

# Use the same recipe as the longitudinal model

long_enet_rec <- long_rec

long_enet_wf <- workflow() |>

add_recipe(long_enet_rec) |>

add_model(enet_mod)

set.seed(42)

long_enet_res <- tune_grid(

long_enet_wf,

resamples = cv_long,

grid = enet_grid,

metrics = metric_set(rmse, mae, rsq),

control = control_grid(save_pred = TRUE)

)

print(collect_metrics(long_enet_res),n=110)# A tibble: 108 × 8

penalty mixture .metric .estimator mean n std_err .config

<dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <chr>

1 0.001 0 mae standard 4.88 6 0.0418 pre0_mod01_post0

2 0.001 0 rmse standard 6.17 6 0.0567 pre0_mod01_post0

3 0.001 0 rsq standard 0.561 6 0.00731 pre0_mod01_post0

4 0.001 0.2 mae standard 4.87 6 0.0407 pre0_mod02_post0

5 0.001 0.2 rmse standard 6.15 6 0.0561 pre0_mod02_post0

6 0.001 0.2 rsq standard 0.563 6 0.00753 pre0_mod02_post0

7 0.001 0.4 mae standard 4.87 6 0.0409 pre0_mod03_post0

8 0.001 0.4 rmse standard 6.15 6 0.0563 pre0_mod03_post0

9 0.001 0.4 rsq standard 0.563 6 0.00753 pre0_mod03_post0

10 0.001 0.6 mae standard 4.87 6 0.0408 pre0_mod04_post0

11 0.001 0.6 rmse standard 6.15 6 0.0561 pre0_mod04_post0

12 0.001 0.6 rsq standard 0.564 6 0.00753 pre0_mod04_post0

13 0.001 0.8 mae standard 4.87 6 0.0407 pre0_mod05_post0

14 0.001 0.8 rmse standard 6.15 6 0.0561 pre0_mod05_post0

15 0.001 0.8 rsq standard 0.563 6 0.00752 pre0_mod05_post0

16 0.001 1 mae standard 4.87 6 0.0407 pre0_mod06_post0

17 0.001 1 rmse standard 6.15 6 0.0561 pre0_mod06_post0

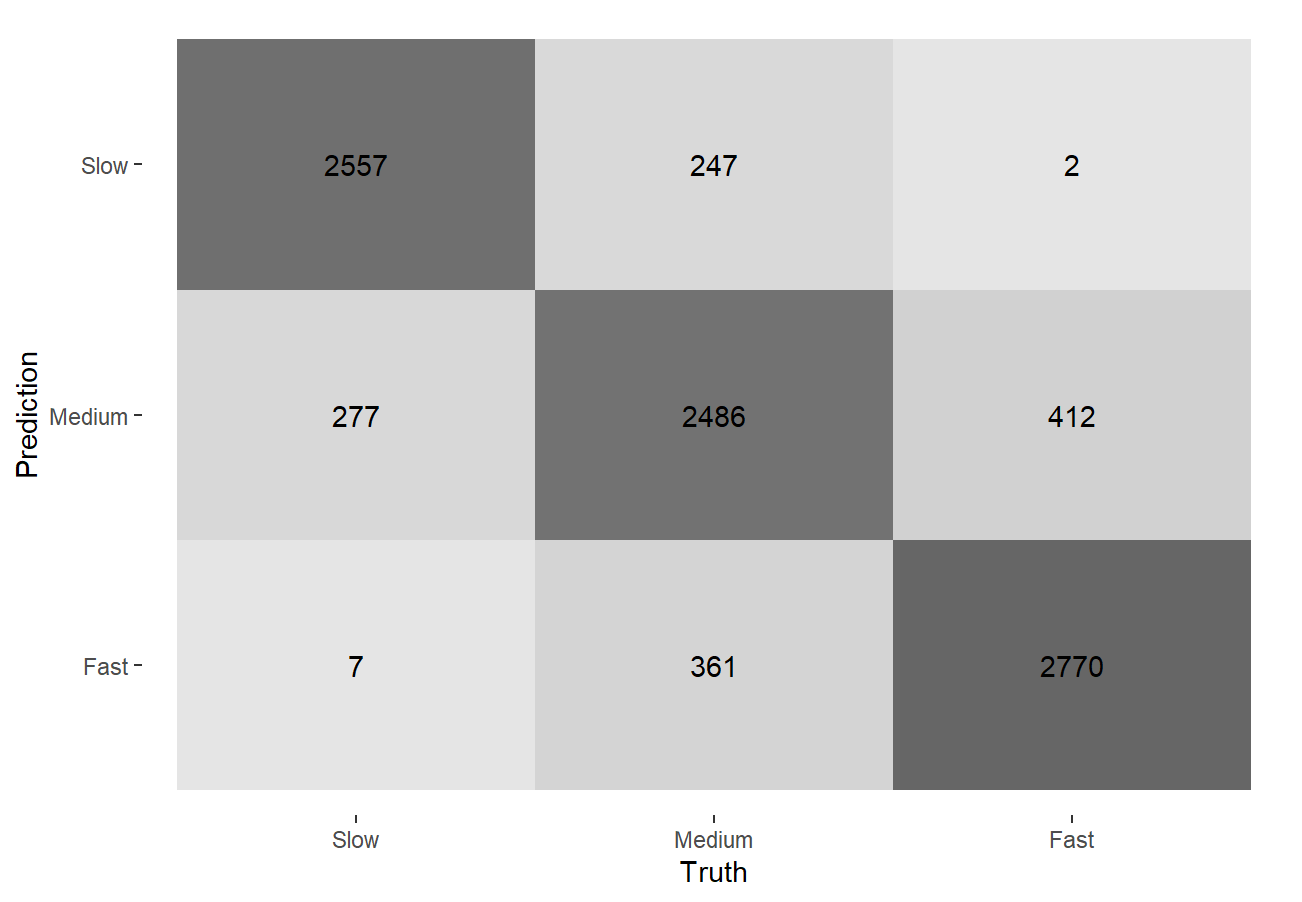

18 0.001 1 rsq standard 0.563 6 0.00752 pre0_mod06_post0