✅ A model solution for the W08 summative

What follows is a possible solution for the W08 summative. If you want to render the .qmd that was used to generate this page for yourselves, use the download button below:

Keep in mind that this is only one possible solution but, by no means, the only one!

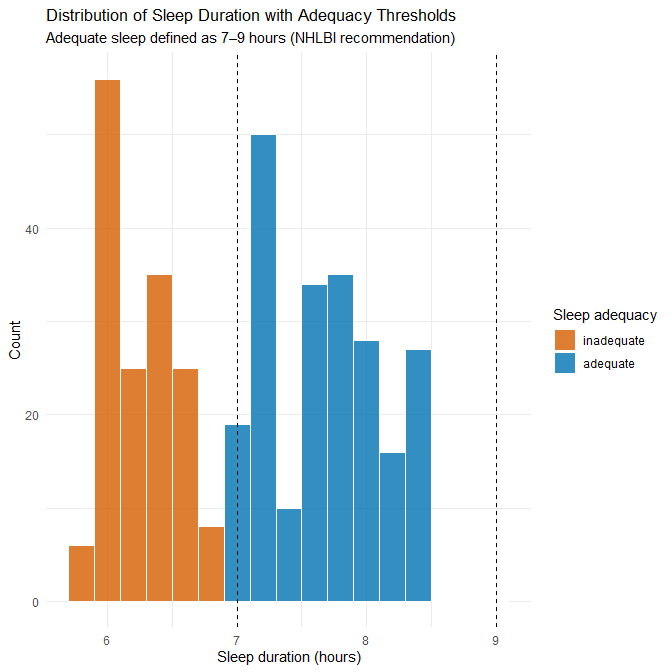

# Load all libraries here; suppress warnings/messages globally via YAML above

library(tidyverse)

library(tidymodels)

library(janitor)

library(skimr)

library(ggcorrplot)

library(vip)

library(ggdist)

library(pdp)

set.seed(123) # for reproducibility of splits/resampling

options(dplyr.summarise.inform = FALSE)- Make sure to load all your libraries in a single code chunk at the beginning of your file. It’s much cleaner than sprinkling loading commands throughout.

- Don’t include any executable

install.packages()commands in your file. This would prevent your.qmdfrom rendering. If you want your readers to know they need to install packages and which ones they should install, then simply include a plain Markdown note on this.

Data loading and preparation

Q1.1 Load the dataset into a DataFrame sleep

# Adjust the path as needed for your setup

sleep <- read_csv("../../data/Sleep_health_and_lifestyle_dataset.csv", show_col_types = FALSE) %>%

clean_names()

glimpse(sleep)

Rows: 374

Columns: 13

$ person_id <dbl> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14,…

$ gender <chr> "Male", "Male", "Male", "Male", "Male", "Male"…

$ age <dbl> 27, 28, 28, 28, 28, 28, 29, 29, 29, 29, 29, 29…

$ occupation <chr> "Software Engineer", "Doctor", "Doctor", "Sale…

$ sleep_duration <dbl> 6.1, 6.2, 6.2, 5.9, 5.9, 5.9, 6.3, 7.8, 7.8, 7…

$ quality_of_sleep <dbl> 6, 6, 6, 4, 4, 4, 6, 7, 7, 7, 6, 7, 6, 6, 6, 6…

$ physical_activity_level <dbl> 42, 60, 60, 30, 30, 30, 40, 75, 75, 75, 30, 75…

$ stress_level <dbl> 6, 8, 8, 8, 8, 8, 7, 6, 6, 6, 8, 6, 8, 8, 8, 8…

$ bmi_category <chr> "Overweight", "Normal", "Normal", "Obese", "Ob…

$ blood_pressure <chr> "126/83", "125/80", "125/80", "140/90", "140/9…

$ heart_rate <dbl> 77, 75, 75, 85, 85, 85, 82, 70, 70, 70, 70, 70…

$ daily_steps <dbl> 4200, 10000, 10000, 3000, 3000, 3000, 3500, 80…

$ sleep_disorder <chr> "None", "None", "None", "Sleep Apnea", "Sleep …We load the CSV file into a tibble called sleep and clean the column names to snake_case for easier use with tidyverse/tidymodels. The dataset includes demographic variables (e.g. age, gender, occupation), lifestyle variables (e.g. physical_activity_level, daily_steps, stress_level), and sleep-related outcomes such as sleep_duration, quality_of_sleep, and sleep_disorder.

The person_id column (if present) is an identifier and should not be used as a predictor in modelling.

When loading the dataset, use a relative file path, and make sure the file is stored in your repository in the same structure as in the material you submit.

Absolute paths (e.g., "/Users/alex/Desktop/data/...") will only work on your own machine and break reproducibility. Relative paths ensure that your .qmd runs correctly on any computer without modification.

Part 1: Data Exploration (15 marks)

Q1.2 Explore and visualise the data

1.2.a Correlations with sleep duration

We want to try and check which variables are most strongly correlated with sleep duration so we construct a correlation matrix based on the datasets’ numeric features (correlation is meaningless for categorical features!)

# Select numeric variables for correlation

sleep_numeric <- sleep %>%

select(where(is.numeric)) %>%

select(-person_id) # drop ID if present

# Correlation matrix

cor_sleep <- cor(sleep_numeric, use = "pairwise.complete.obs")

# Focus on correlations with sleep_duration

cor_sleep[,"sleep_duration"] %>% sort(decreasing = TRUE)

sleep_duration quality_of_sleep age

1.00000000 0.88321300 0.34470936

physical_activity_level daily_steps heart_rate

0.21236031 -0.03953254 -0.51645489

stress_level

-0.81102303 We visualise these correlations as a heatmap.

# Visual correlation plot

ggcorrplot(

cor_sleep,

hc.order = TRUE,

type = "lower",

lab = TRUE, # show correlation labels

lab_size = 3,

outline.col = "white",

colors = c("#8CDEDC", "white", "#841C26")

) +

theme(

axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90, hjust = 1)

)

The correlation vector and heatmap help us identify which numeric variables show meaningful linear associations with sleep_duration.

From the matrix we observe:

Strong positive association between sleep_duration and quality_of_sleep (≈ 0.88). This is expected: participants who report higher sleep quality tend to also report sleeping more hours. Because both variables reflect aspects of sleep, some degree of correlation is structurally built into the dataset.

Moderate positive associations with daily_steps (≈ 0.21) and age (≈ 0.34). These suggest that, in this synthetic sample, people who take more daily steps or who are slightly older report somewhat longer sleep. These correlations are modest and should not be over-interpreted.

Near-zero associations with physical_activity_level (≈ −0.04). Despite intuition that more activity might improve sleep duration, the synthetic data does not show a meaningful linear relationship here.

Moderate negative associations with stress_level (≈ −0.52). Participants with higher stress levels tend to sleep fewer hours. This is consistent with real-world findings, but we must remember that correlation does not indicate cause.

Weak negative associations with heart_rate (≈ −0.23). This suggests that higher resting heart rate is slightly associated with shorter sleep, though again the relationship is weak.

Overall, the strongest signals relate to quality_of_sleep and stress_level, which makes substantive sense: both are conceptually tied to sleep outcomes. Other numeric variables exhibit weak correlations, indicating the relationship between lifestyle factors and sleep duration is complex and potentially non-linear.

As always, correlations capture association rather than causation, so these patterns should be used to motivate modelling decisions (e.g., variable selection) rather than to draw causal conclusions.

1.2.b Subgroup differences

Sleep duration by gender

We begin by examining whether sleep duration differs across genders.

sleep %>% count(gender)# A tibble: 2 × 2

gender n

<chr> <int>

1 Female 185

2 Male 189The dataset includes 185 females and 189 males, providing a balanced sample for comparison.

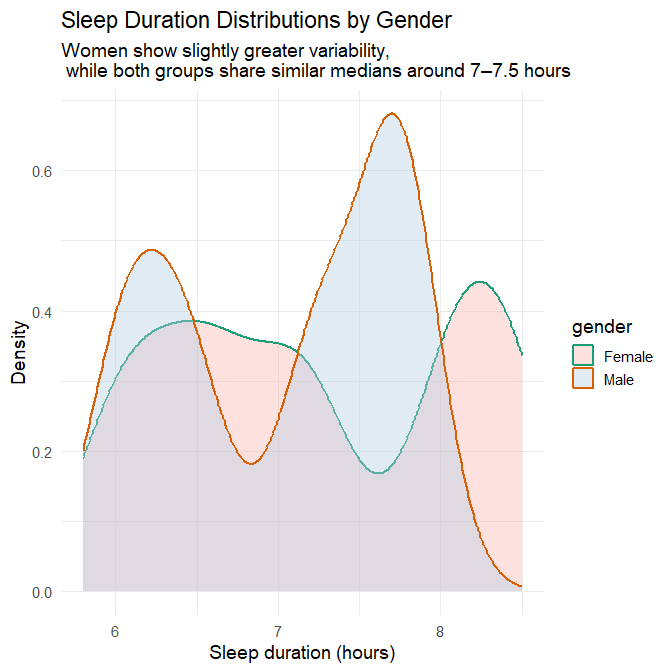

Distribution plot (density)

sleep %>%

ggplot(aes(x = sleep_duration, fill = gender, colour = gender)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.4, size = 1) +

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Pastel1") +

scale_colour_brewer(palette = "Dark2") +

labs(

title = "Sleep Duration Distributions by Gender",

subtitle = "Women show slightly greater variability, \n while both groups share similar medians around 7–7.5 hours",

x = "Sleep duration (hours)",

y = "Density"

) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14)

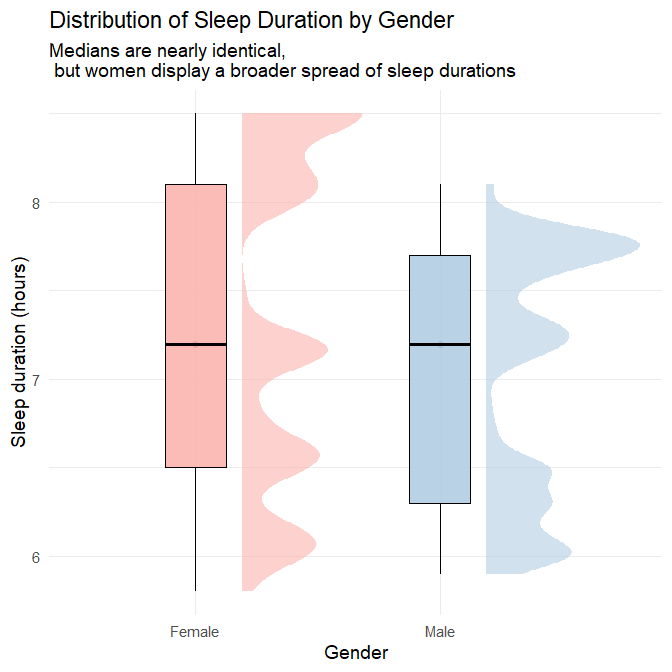

Half-violin + boxplot hybrid

sleep %>%

ggplot(aes(x = gender, y = sleep_duration, fill = gender)) +

stat_halfeye(

adjust = 0.6,

width = 0.7,

.width = 0,

justification = -0.3,

alpha = 0.6

) +

geom_boxplot(

width = 0.25,

outlier.shape = NA,

alpha = 0.9,

colour = "black"

) +

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Pastel1") +

labs(

title = "Distribution of Sleep Duration by Gender",

subtitle = "Medians are nearly identical, \n but women display a broader spread of sleep durations",

x = "Gender",

y = "Sleep duration (hours)"

) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14) +

theme(legend.position = "none")

Plots’ interpretation

The two visualisations together provide a detailed and nuanced comparison of sleep patterns between genders.

1. Central tendency

Both the density plot and the half-violin/boxplot hybrid show that:

- Men and women share a very similar median sleep duration, slightly above 7 hours.

- The bulk of observations for both genders fall between 7 and 7.5 hours.

- There is no evidence of a systematic shift in typical sleep duration between genders.

This indicates that average sleep duration does not differ meaningfully by gender in this dataset.

2. Variability, spread, and range

The full distributions reveal subtleties that would be invisible if we looked only at the median:

Women show slightly greater variability in sleep duration, as indicated by:

- a broader density curve,

- a longer left-tail (more short sleepers),

- a longer right-tail (more long sleepers),

- a wider half-violin shape,

- both lower minimum and higher maximum values than men.

Men exhibit a more concentrated pattern, reflected in:

- a noticeably “peakier” density curve,

- a narrower half-violin span,

- fewer extreme values on either end.

This difference is subtle, but consistent across both visualisations: women’s sleep durations vary more widely, whereas men cluster more tightly around the median.

3. Shape of distributions

- The female density curve is flatter and more spread out, indicating more heterogeneity.

- The male density curve is sharper, reflecting greater uniformity.

- Both distributions remain unimodal, centred around the same dominant peak.

These shapes confirm that the difference between genders lies not in typical sleep, but in how consistently they sleep.

Take-away

There is no meaningful difference in central tendency (mean or median) between men and women in this dataset. However:

- Women show a broader range, implying more night-to-night or individual-to-individual variation.

- Men show more consistency, with most values clustered near the median.

This illustrates why EDA should examine distribution shape, not just summary statistics.

Explanatory context

Although this dataset is synthetic, subtle gender differences in sleep variability have been documented in real-world sleep research. One consistent finding is that women experience more sleep disturbances and insomnia symptoms, even when total sleep duration is similar to men (Zhang and Wing 2006) (R. H. Y. Li et al. 2002) . Such disturbances can increase night-to-night variability in overall sleep hours.

Research on couples also shows that women are more susceptible to sleep-maintenance disruptions linked to household or partner-related factors, such as nocturnal awakenings and mismatched routines (Meadows and Arber 2012). While this research does not directly address total sleep duration, it illustrates how social patterns within households can produce less consistent nightly sleep for women.

Broader sociological research reinforces this picture. (Burgard and Ailshire 2013) show that women often have less discretionary time available for sleep due to unequal divisions of domestic labour, childcare responsibilities, and work–family conflict. These social constraints can lead to more irregular sleep schedules, even when average total sleep time is similar.

Additionally, caregiving responsibilities — still disproportionately carried by women — have been linked to increased sleep difficulties and irregular sleep patterns (Straat, Willems, and Bracke 2020) . Women also tend to experience greater variability in daily stress exposure (Almeida and Kessler 1998), and stress is a well-established contributor to fragmented and inconsistent sleep (Akerstedt 2006).

Taken together, these findings support the idea that greater variability in women’s sleep can arise from a combination of:

- higher rates of insomnia and nocturnal disturbances,

- greater exposure to household or partner-related sleep disruptions,

- unequal caregiving and domestic responsibilities,

- and stress-related sleep fragmentation.

These mechanisms do not imply biological determinism; rather, they reflect well-documented social, behavioural, and psychological factors that may help explain the pattern observed in this dataset.

Sleep Duration by Age Group

Creating age groups

We begin by creating an age_group variable, since the dataset does not contain one by default. Here we define two broad groups commonly used in sleep epidemiology: 26–40 and 41–60.

sleep <- sleep %>%

mutate(

age_group = case_when(

age >= 26 & age <= 40 ~ "26–40",

age >= 41 & age <= 60 ~ "41–60",

TRUE ~ NA_character_

),

age_group = factor(age_group, levels = c("26–40", "41–60"))

)Age group counts

We check how participants are distributed across age groups.

sleep %>%

count(age_group)# A tibble: 2 × 2

age_group n

<fct> <int>

1 26–40 165

2 41–60 209Comment: The age groups are not perfectly balanced (165 vs. 209 participants), but both groups have sufficiently large samples to support meaningful comparison.

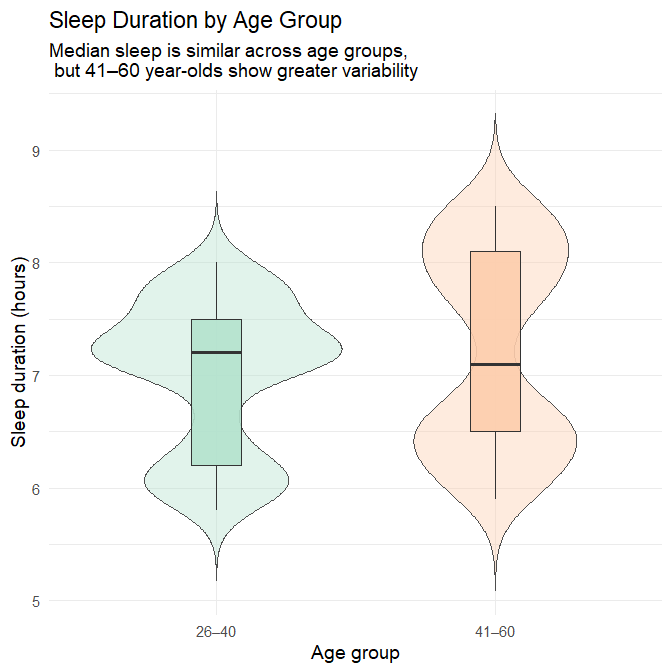

Plot: Sleep duration by age group

We now visualise the distribution of sleep duration for each age group using a violin–boxplot combination, which shows both central tendencies and distribution shapes.

sleep %>%

ggplot(aes(x = age_group, y = sleep_duration, fill = age_group)) +

geom_violin(alpha = 0.4, trim = FALSE, colour = "grey30") +

geom_boxplot(width = 0.18, alpha = 0.9, outlier.shape = NA, colour = "grey20") +

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Pastel2") +

labs(

title = "Sleep Duration by Age Group",

subtitle = "Median sleep is similar across age groups, \n but 41–60 year-olds show greater variability",

x = "Age group",

y = "Sleep duration (hours)"

) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14) +

theme(legend.position = "none")

Interpretation

The median sleep duration is nearly identical across the two age groups, with both centred slightly above seven hours. This suggests that, at the population level, typical sleep quantity remains relatively stable from early adulthood into midlife.

What differs more visibly is the shape of the distributions:

Adults aged 26–40 show a tighter clustering of sleep durations, with most individuals sleeping between 6.5 and 8 hours.

Adults aged 41–60 display a broader spread, including:

more short sleepers (below ~6 hours), and

more long sleepers (above ~8.5 hours).

This pattern indicates that while average sleep duration is consistent, sleep behaviour becomes more heterogeneous in later adulthood, with a subset of individuals experiencing markedly shorter or longer sleep durations than the typical range.

Explanatory context

Research on sleep and ageing shows patterns that help contextualise this distribution:

Normal ageing involves changes in sleep continuity, including increased awakenings and more fragmented sleep (J. Li, Vitiello, and Gooneratne 2018). These changes do not necessarily reduce average sleep duration but often introduce greater night-to-night variability, consistent with our broader spread in the older group.

Longer-than-average sleep duration in older adults has been associated with elevated risk of later cognitive decline (Ma et al. 2020) and dementia in prospective analyses (Fan et al. 2019) (Bulycheva et al. 2024). This does not imply dementia within this synthetic dataset, but it illustrates why a subgroup of long sleepers is more plausible in older than younger adults.

Together, these findings support the interpretation that the wider distribution in the 41–60 group is consistent with known age-related variability in sleep patterns.

Sleep Duration by Occupation

Occupation counts

We first examine how many individuals represent each occupational category.

sleep %>%

count(occupation, sort = TRUE)# A tibble: 11 × 2

occupation n

<chr> <int>

1 Nurse 73

2 Doctor 71

3 Engineer 63

4 Lawyer 47

5 Teacher 40

6 Accountant 37

7 Salesperson 32

8 Scientist 4

9 Software Engineer 4

10 Sales Representative 2

11 Manager 1Comment: Some occupations (e.g., nurses, doctors, engineers) have large sample sizes, while others (e.g., scientists, sales representatives, manager) contain very few participants. This uneven representation must be considered when interpreting differences.

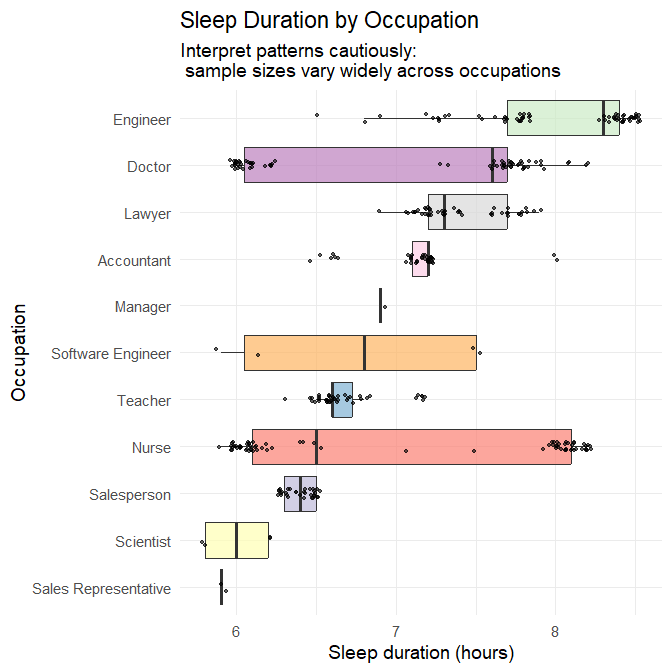

Plot: Sleep duration by occupation

We visualise occupational differences, ordering occupations by median sleep duration.

sleep %>%

mutate(occupation = fct_reorder(occupation, sleep_duration, .fun = median)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = sleep_duration, y = occupation, fill = occupation)) +

geom_boxplot(alpha = 0.7, outlier.shape = NA, colour = "grey20") +

geom_jitter(height = 0.1, alpha = 0.6, size = 1) +

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Set3") +

labs(

title = "Sleep Duration by Occupation",

subtitle = "Interpret patterns cautiously:\n sample sizes vary widely across occupations",

x = "Sleep duration (hours)",

y = "Occupation"

) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14) +

theme(legend.position = "none")

Interpretation

Well-represented occupations

For occupations with large sample sizes (N ≳ 30), meaningful patterns emerge:

- Nurses show a wide distribution of sleep durations, ranging roughly 6–8.5 hours.

- Doctors also show substantial variability.

- Teachers, accountants, engineers, lawyers, and salespeople show narrower distributions centred near 7 hours.

These patterns align with differences in schedule regularity: shift-based professions such as nursing and medicine exhibit more varied sleep timing and duration, whereas more consistent daytime roles produce tighter clustering.

Under-represented occupations

Occupations with N < 10 cannot support reliable inference. Their boxplots are largely driven by individual values, and observed variation should not be overinterpreted.

Take-away

Occupational differences appear consistent with known impacts of work schedules on sleep, but unequal sample sizes strongly limit interpretability for several categories.

Explanatory context

The observed patterns align with robust occupational health findings:

- Systematic reviews describe shift work as associated with shorter and more irregular sleep, circadian disruption, and increased sleepiness (Harrington 1994) (Wu et al. 2022).

- Nurses working 12-hour shifts average only ~5.5 hours of sleep between shifts, experience cumulative fatigue, and display increased sleepiness across consecutive workdays (Geiger-Brown et al. 2012).

- Limiting extended shifts in medical interns significantly increases total sleep time and reduces attentional failures (Lockley et al. 2004).

- Observational work shows that extended or irregular shifts in medical trainees lead to substantial variability in sleep (Basner et al. 2017).

These findings support the interpretation that wide sleep variability in nurses and doctors is credible, while categories with very small sample sizes remain unreliable for inference.

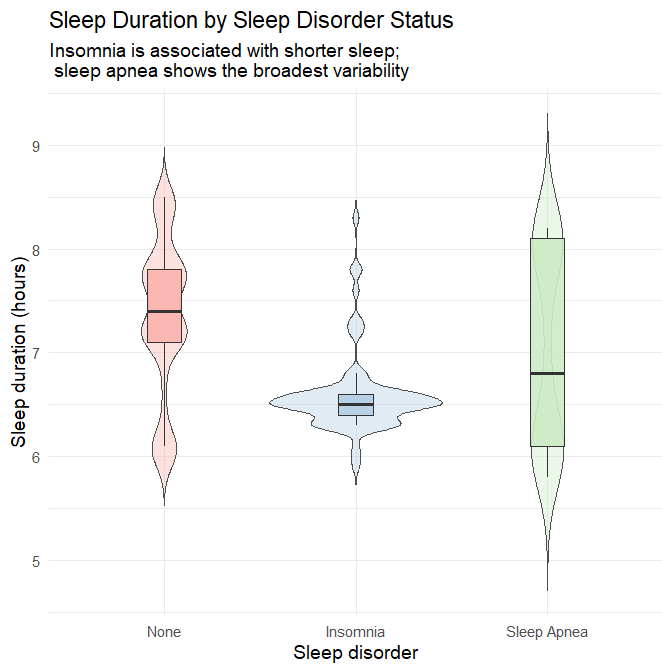

Sleep Duration by Sleep Disorder Status

Sleep disorder counts

We check the representation of each disorder category.

sleep %>%

count(sleep_disorder)# A tibble: 3 × 2

sleep_disorder n

<chr> <int>

1 Insomnia 77

2 None 219

3 Sleep Apnea 78Comment: All three groups (None, Insomnia, Sleep Apnea) are well represented. Unlike the occupation variable, we can interpret differences with confidence.

Plot: Sleep duration by disorder

sleep %>%

mutate(sleep_disorder = fct_relevel(sleep_disorder, "None", "Insomnia", "Sleep Apnea")) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = sleep_disorder, y = sleep_duration, fill = sleep_disorder)) +

geom_violin(alpha = 0.4, trim = FALSE, colour = "grey30") +

geom_boxplot(width = 0.18, alpha = 0.9, outlier.shape = NA, colour = "grey20") +

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Pastel1") +

labs(

title = "Sleep Duration by Sleep Disorder Status",

subtitle = "Insomnia is associated with shorter sleep;\n sleep apnea shows the broadest variability",

x = "Sleep disorder",

y = "Sleep duration (hours)"

) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14) +

theme(legend.position = "none")

Interpretation

No disorder: Participants without sleep disorders sleep the most and show moderate variability.

Insomnia: This group exhibits the lowest median sleep duration (~6.4 hours) with a narrow, left-shifted distribution. Most individuals cluster between 6–6.8 hours, reflecting the diagnostic hallmark of insomnia: difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep.

Sleep apnea: Median sleep duration is somewhat lower than the “no disorder” group, but the distribution is notably wide, with both short and long sleepers. This reflects:

- fragmented sleep due to repeated apneic events

- compensatory longer sleep in some individuals due to excessive daytime sleepiness

Take-away

Sleep disorder status is highly informative: insomnia predicts consistently shortened sleep, while sleep apnea predicts variable and disrupted sleep patterns.

Explanatory context

Insomnia is defined by difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, typically resulting in reduced, non-restorative sleep (American Psychiatric Association 2013) (Roth 2007) (American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014). This aligns neatly with the narrow, reduced sleep durations seen in the insomnia group.

Obstructive sleep apnea is characterised by repeated upper-airway obstruction, oxygen desaturation, and recurrent arousals, producing fragmented sleep (Jordan, McSharry, and Malhotra 2014). Such fragmentation yields both:

- short sleep (due to awakenings) and

- longer sleep in some cases (due to compensatory hypersomnia).

These documented clinical patterns strongly support the observed distributions.

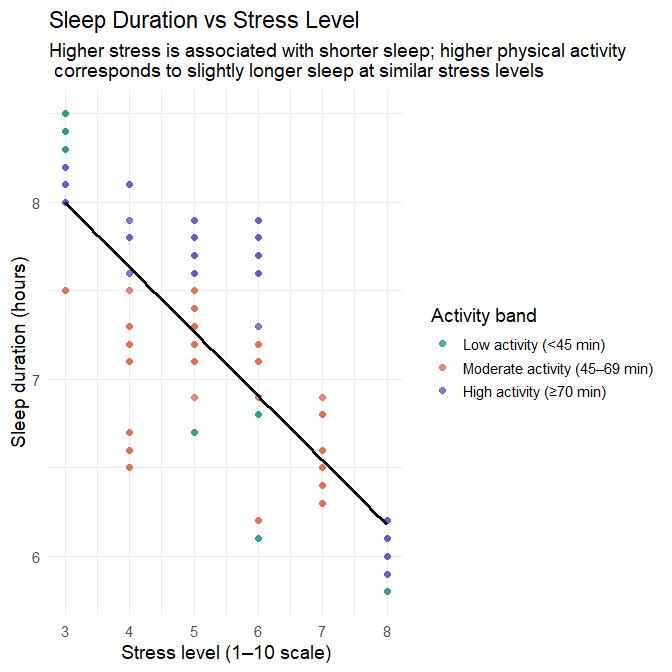

1.2.c Multivariable Plot: Sleep Duration, Stress Level, and Physical Activity

Understanding how sleep duration relates to a single predictor is informative, but real-world behaviours are typically shaped by multiple factors at once. In this section, we examine a multivariable relationship by exploring how:

- sleep duration varies with

- stress level (primary predictor), while

- physical activity is represented through colour-coded activity bands.

This visualisation helps us assess whether physical activity appears to modify or contextualise the relationship between stress and sleep.

Step 1 — Create a banded physical-activity variable

Before plotting, we organise physical activity into meaningful bands. This avoids the visual clutter of colouring by dozens of distinct numeric values and allows clearer interpretation.

sleep <- sleep %>%

mutate(

activity_band = case_when(

physical_activity_level < 45 ~ "Low activity (<45 min)",

physical_activity_level < 70 ~ "Moderate activity (45–69 min)",

TRUE ~ "High activity (≥70 min)"

) %>% factor(

levels = c(

"Low activity (<45 min)",

"Moderate activity (45–69 min)",

"High activity (≥70 min)"

)

)

)Step 2 — Inspect how many participants fall into each activity band

We check the distribution across bands to ensure each category has enough observations for meaningful interpretation.

sleep %>%

count(activity_band)# A tibble: 3 × 2

activity_band n

<fct> <int>

1 Low activity (<45 min) 82

2 Moderate activity (45–69 min) 151

3 High activity (≥70 min) 141Comment:

All three activity bands (Low activity, Moderate activity, High activity) are well represented. We can interpret the coloured clusters with confidence.

Step 3 — Create the multivariable plot

We now plot sleep duration against stress level, colouring the points according to the newly created activity bands. A linear smoothing line summarises the overall stress–sleep association.

sleep %>%

ggplot(aes(x = stress_level,

y = sleep_duration,

colour = activity_band)) +

geom_point(size = 2, alpha = 0.8) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, colour = "black") +

scale_colour_manual(

values = c(

"Low activity (<45 min)" = "#2A9D8F",

"Moderate activity (45–69 min)" = "#E76F51",

"High activity (≥70 min)" = "#6A5ACD"

)

) +

labs(

title = "Sleep Duration vs Stress Level",

subtitle = "Higher stress is associated with shorter sleep; higher physical activity\n corresponds to slightly longer sleep at similar stress levels",

x = "Stress level (1–10 scale)",

y = "Sleep duration (hours)",

colour = "Activity band"

) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14)

Interpretation

1. Main association: stress level and sleep duration

The fitted line shows a clear negative association:

- As stress level increases, sleep duration decreases.

- The downward trend is smooth and approximately linear across the observed range.

- The clustering of points around the line suggests that stress is a relatively strong predictor of sleep duration in this dataset.

This indicates that stress is likely to play a major role in the regression modelling that follows.

2. Added insight from physical activity

The coloured activity bands add a second dimension:

- Participants in the high-activity band (≥70 min/day) tend to appear slightly higher on the sleep-duration axis at each stress level.

- Participants in the low-activity band (<45 min/day) tend to appear lower.

- The moderate-activity band falls in between, with some overlap.

These differences are modest but consistent:

Even at the same stress level, participants with higher physical activity tend to sleep slightly longer than those with lower activity.

This pattern reflects two complementary strands of evidence:

- Regular physical activity is associated with better sleep onset and sleep continuity, and with improvements in overall sleep quality (Kredlow et al. 2015) (Kline 2014).

- Physical activity has been shown to reduce stress-related neuroendocrine activation and improve resilience to chronic stress, which may offer a plausible mechanism for the slightly longer sleep observed among more active individuals in this dataset (Tsatsoulis and Fountoulakis 2006).

Together, these findings offer a behavioural and physiological explanation for the vertical separation seen between activity bands.

3. Full multivariable pattern

Considering both predictors jointly:

- Stress level exerts the strongest influence on sleep duration.

- Physical activity introduces a secondary, “buffering” pattern, where active individuals tend to sleep slightly longer.

- The negative association between stress and sleep remains present across all activity bands.

This mirrors the type of structure we will model statistically in Part 2.

Key takeaway

This multivariable plot shows that:

- Stress is a strong and consistently negative predictor of sleep duration.

- Physical activity provides a modest buffering effect, with more active participants sleeping slightly longer at similar stress levels.

- Combining predictors visually yields a richer understanding of the structure in the data—insights that will inform later modelling decisions.

1.2.d Missing Data and Anomalies

Before moving on to modelling, we must ensure the dataset is complete and free from problematic anomalies. Missingness and outliers can influence regression and classification in undesirable ways (e.g., biased coefficients, unstable splits, inflated errors). In this dataset, both steps are straightforward but still essential.

1. Checking for Missing Data

We first compute the number of missing values in each column:

sleep %>%

summarise(across(everything(), ~ sum(is.na(.)))) %>%

pivot_longer(everything(),

names_to = "variable",

values_to = "n_missing")# A tibble: 15 × 2

variable n_missing

<chr> <int>

1 person_id 0

2 gender 0

3 age 0

4 occupation 0

5 sleep_duration 0

6 quality_of_sleep 0

7 physical_activity_level 0

8 stress_level 0

9 bmi_category 0

10 blood_pressure 0

11 heart_rate 0

12 daily_steps 0

13 sleep_disorder 0

14 age_group 0

15 activity_band 0We also examine summary statistics and variable types:

skim(sleep)── Data Summary ────────────────────────

Values

Name sleep

Number of rows 374

Number of columns 15

_______________________

Column type frequency:

character 5

factor 2

numeric 8

________________________

Group variables None

── Variable type: character ────────────────────────────────────────────────────

skim_variable n_missing complete_rate min max empty n_unique whitespace

1 gender 0 1 4 6 0 2 0

2 occupation 0 1 5 20 0 11 0

3 bmi_category 0 1 5 13 0 4 0

4 blood_pressure 0 1 6 6 0 25 0

5 sleep_disorder 0 1 4 11 0 3 0

── Variable type: factor ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────

skim_variable n_missing complete_rate ordered n_unique

1 age_group 0 1 FALSE 2

2 activity_band 0 1 FALSE 3

top_counts

1 41–: 209, 26–: 165

2 Mod: 151, Hig: 141, Low: 82

── Variable type: numeric ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────

skim_variable n_missing complete_rate mean sd p0 p25

1 person_id 0 1 188. 108. 1 94.2

2 age 0 1 42.2 8.67 27 35.2

3 sleep_duration 0 1 7.13 0.796 5.8 6.4

4 quality_of_sleep 0 1 7.31 1.20 4 6

5 physical_activity_level 0 1 59.2 20.8 30 45

6 stress_level 0 1 5.39 1.77 3 4

7 heart_rate 0 1 70.2 4.14 65 68

8 daily_steps 0 1 6817. 1618. 3000 5600

p50 p75 p100 hist

1 188. 281. 374 ▇▇▇▇▇

2 43 50 59 ▆▆▇▃▅

3 7.2 7.8 8.5 ▇▆▇▇▆

4 7 8 9 ▁▇▆▇▅

5 60 75 90 ▇▇▇▇▇

6 5 7 8 ▇▃▂▃▃

7 70 72 86 ▇▇▂▁▁

8 7000 8000 10000 ▁▅▇▆▂Result:

This synthetic Kaggle dataset contains no missing values in any variable. This is unusual for real-world datasets but expected for synthetic data.

2. Preparing for anomaly detection: Split blood pressure into numeric components

The variable blood_pressure is stored as a single string in "systolic/diastolic" format. To detect anomalies properly — and to model the predictors later — it is preferable to split this into two numeric columns.

Reformat blood pressure:

sleep <- sleep %>%

separate(blood_pressure,

into = c("bp_systolic", "bp_diastolic"),

sep = "/",

convert = TRUE)Why this matters:

- A string variable cannot be used directly in regression or classification.

- Systolic and diastolic pressures have different physiological interpretations, so treating them separately is more meaningful.

- Splitting allows us to check each component for anomalies (e.g., systolic < 90 or > 200 mmHg).

We now have two clean numeric predictors: sleep$bp_systolic and sleep$bp_diastolic.

3. Checking for anomalies

Even without missing data, numerical variables may contain values that fall outside expected physiological or behavioural ranges. In real-world datasets, anomalies often arise from device errors, data-entry mistakes, unit mix-ups, or genuinely unusual human situations. We therefore inspect each major numeric variable in turn to understand whether any values require attention before modelling.

3.1 Sleep duration

Code: Examine the range of sleep duration

summary(sleep$sleep_duration) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

5.800 6.400 7.200 7.132 7.800 8.500Interpretation

All sleep durations fall between 5.8 and 8.5 hours, which represents a typical mid-range adult sleep pattern.

However, in real-world sleep-health datasets, we normally find a much broader and more irregular spread, including:

Very short sleep (< 3 hours) — which is not necessarily an anomaly. It can occur with:

- night-shift work

- medical trainees working overnight

- caregiving responsibilities

- acute or chronic insomnia

- high stress or crisis situations

- severe mental health episodes

Very long sleep (> 11–12 hours) — which may arise in:

- hypersomnia disorders

- bipolar depressive episodes

- neurological illness

- chronic fatigue

- recovery after prolonged sleep deprivation

- sedating medications

Thus, the absence of both unusually short and unusually long sleepers — and the smooth, tightly bounded distribution — strongly suggests synthetic generation rather than natural variation.

In real datasets, such extreme values would require contextual judgment rather than automatic removal.

3.2 Heart rate

Code: Examine resting heart rate values

summary(sleep$heart_rate) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

65.00 68.00 70.00 70.17 72.00 86.00Interpretation

All heart rates fall between 65 and 86 bpm, entirely within the expected resting range for adults (~60–100 bpm).

In real physiological datasets, we would often expect:

Bradycardia (< 50 bpm) Seen in endurance athletes, individuals on certain medications, or those with conduction abnormalities.

Tachycardia (> 110 bpm) Common in cases of illness, anxiety, pain, dehydration, stimulant use, endocrine disorders, or device misreads.

The tight clustering in this dataset — without unusually low or high values — again signals synthetic smoothing.

3.3 Daily steps

Code: Examine step-count distribution

summary(sleep$daily_steps) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

3000 5600 7000 6817 8000 10000Interpretation

All values lie within a plausible human activity range (3,000–10,000 steps per day). However, real activity datasets usually include:

- very low step counts (< 500/day) — common among people with limited mobility or during illness,

- very high values (> 20,000) — typical for athletes, healthcare workers, or delivery staff,

- implausible values (> 50,000) — often indicating device malfunction or unit confusion.

The capped maximum of exactly 10,000 steps, a culturally recognised “goal,” further suggests synthetic construction rather than observed behaviour.

3.4 Physical activity level (minutes/day)

Code: Examine daily activity minutes

summary(sleep$physical_activity_level) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

30.00 45.00 60.00 59.17 75.00 90.00Interpretation

All physical-activity values fall between 30 and 90 minutes, which is reasonable.

However, true observational datasets almost always include:

- nearly sedentary days (0–10 minutes)

- occasional extreme activity (> 150 minutes/day)

- misreported values (e.g., “300 minutes” instead of “30”)

- device-originated artefacts

The absence of both low-activity and high-activity individuals makes the distribution unnaturally regular — again consistent with synthetic data.

3.5 Blood pressure (after splitting)

Code: Examine systolic and diastolic pressure

summary(sleep$bp_systolic)

summary(sleep$bp_diastolic)> summary(sleep$bp_systolic)

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

115.0 125.0 130.0 128.6 135.0 142.0

> summary(sleep$bp_diastolic)

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

75.00 80.00 85.00 84.65 90.00 95.00Interpretation

These values span typical normal and mildly hypertensive ranges.

Real-world blood pressure data usually include:

hypotensive values (< 90/60)

severely hypertensive values (> 180/120)

measurement artefacts, such as:

- reversed values (e.g., “85/140”),

- truncated values (e.g., “120/8”),

- device-driven rounding or plateauing.

The absence of such irregularities again indicates a synthetic dataset.

🧠 Final Interpretation and implications for modelling

Across all numeric variables, we observe a consistent pattern:

- All values fall within realistic adult ranges,

- but the distributions are unusually tight, smooth, and bounded,

- lacking the extremes, irregularities, measurement noise, and rare events typical of real observational data.

This strongly suggests that the dataset has been synthetically generated with constraints designed to produce “clean” values.

Why this matters for modelling

When we work with real-world sleep, lifestyle, or clinical datasets, anomaly-handling becomes a central part of the workflow:

- very short or very long sleep durations may be meaningful, not errors,

- extreme heart rates or blood pressures may indicate important subgroups,

- unusually low or high activity metrics may reflect occupational patterns or health conditions,

- anomalies may arise from measurement error and require correction or transformation.

In this dataset, because values have been artificially regularised, we can proceed directly into modelling without worrying about anomaly removal or variable transformation.

However, it is important to recognise that this is a special case: anomaly detection is a critical step in most applied machine learning and statistical modelling projects.

Part 2: Regression – Predicting Sleep Duration (35 marks)

Q2.1 Train–test split

Before fitting any regression models, we first create separate datasets for training (used to estimate the model and tune any necessary components) and testing (used only at the end to evaluate how well the model generalises to unseen data). It is essential that this split is performed before any modelling-specific preprocessing so that the test dataset remains a truly independent sample of new, unseen observations.

Code

set.seed(123) # ensures reproducible random splitting

# Remove the EDA-only derived variables

sleep_reg <- sleep %>%

select(-age_group, -activity_band)

# Create an 80/20 train–test split

sleep_split <- initial_split(sleep_reg, prop = 0.8)

sleep_train <- training(sleep_split)

sleep_test <- testing(sleep_split)

nrow(sleep_train); nrow(sleep_test)[1] 299

[1] 75Interpretation

We use an 80% training / 20% testing split. This proportion provides:

- a training set large enough to estimate regression parameters reliably and to support internal resampling (e.g., cross-validation), and

- a test set sufficiently large to give an unbiased and reasonably stable estimate of out-of-sample performance.

Because the dataset is cross-sectional (not longitudinal, not hierarchical, and not time-ordered), a simple random split is appropriate. We specify a fixed set.seed() to ensure full reproducibility, guaranteeing that the same rows will appear in the training and test sets every time the analysis is run.

Stratification is commonly used when the outcome variable is categorical and imbalanced, such as in classification problems where one level is rare. However, stratification may also be applied to predictor variables, particularly when:

- there are important subgroups that are small,

- there is a risk that a purely random split might exclude those subgroups from the test set,

- or the analyst wants to ensure consistent representation of specific categories.

In this dataset, several variables could reasonably justify stratification:

1. Sleep disorder

The distribution is strongly imbalanced:

- None: 219

- Insomnia: 77

- Sleep Apnea: 78

Stratifying by sleep_disorder would ensure that both the training and test sets preserve a similar proportion of the three groups, which may be useful if we later wish to examine model performance across disorder types.

2. Occupation

This variable includes multiple extremely rare categories, including occupations with only 1–4 observations (“Manager,” “Sales Representative,” “Scientist,” “Software Engineer”). Stratification could prevent these rare occupations from disappearing entirely from either dataset. This may be important if certain occupations are believed to be associated with sleep behaviours or if the model needs to represent all job types during evaluation.

3. Gender

While reasonably balanced overall, stratifying on gender could still be beneficial if separate gender-specific model comparisons are planned later or if we want to enforce equal representation in both splits.

Why we do not stratify here

For this analysis, stratification is not required because:

- the target variable (

sleep_duration) is continuous, - the modelling task focuses on overall predictive performance rather than subgroup-specific estimates, and

- the rare categories, although notable, do not meaningfully compromise the validity of a random split for this particular regression task.

Nonetheless, stratification remains a legitimate and defensible choice depending on the modelling goals, and you may choose to apply it if your focus were different (e.g., fairness across subgroups, diagnostic comparisons, or occupation-specific prediction).

Some categories — especially within occupation — are extremely rare. For example:

- “Manager” appears only once,

- “Sales Representative” appears only twice,

- “Scientist” and “Software Engineer” appear only four times each.

While it may be tempting to collapse such ultra-rare categories into an “Other” group before the train–test split, this would be a methodological error.

Why collapsing before the split is a problem

If rare categories are merged before splitting:

- you are using the entire dataset to decide which categories are “rare,”

- the test set therefore influences the preprocessing decisions,

- and this causes data leakage, because the test data is indirectly shaping the modelling pipeline.

This violates the core principle that the test set must represent entirely new, unseen data.

Correct procedure

All handling of rare categories should occur inside the tidymodels recipe, after the train–test split. This ensures that:

- the recipe learns which levels are rare from the training data only,

- the test set does not influence preprocessing decisions,

- and categorisation decisions are applied to the test set in exactly the same way as they are applied to the training set.

tidymodels provides specific steps for this, including:

step_other(occupation, threshold = ...)to collapse rare levels,step_novel(occupation)to safely handle levels appearing only in the test set,step_dummy(occupation)to encode categories consistently.

Keeping all of these steps inside the recipe preserves the validity and independence of the test set and ensures that no part of the modelling pipeline inadvertently incorporates information from future (test) observations.

Q2.2 Baseline linear regression model

To establish a baseline, we fit a multiple linear regression model predicting sleep_duration using all available predictors (excluding identifiers). A baseline model provides an interpretable reference against which more advanced or flexible models can later be compared. It also helps us understand which predictors appear influential before we apply feature engineering, transformations, or alternative algorithms.

All preprocessing is carried out inside a tidymodels recipe, ensuring that:

- the recipe is trained only on the training data,

- the transformations are applied consistently to both training and test sets,

- and no information from the test set leaks into the modelling process.

1. Baseline recipe

We include all non-ID variables as predictors. This is deliberate: the purpose of a baseline model is to incorporate as much information as possible at first, so we can later judge whether improvements truly matter.

Because some categorical variables — especially occupation — contain extremely rare categories, we use step_novel() and step_other() to handle them safely.

step_novel()creates a placeholder level for any category that might appear only in the test set (or future data) but not in the training set.step_other()collapses ultra-rare categories (based on training-set frequencies) into an"other"category, preventing unstable dummy columns and rank-deficient design matrices.

Performing these steps inside the recipe ensures that the training data alone determines:

- what counts as “rare,”

- which levels get collapsed, and

- how new or previously unseen levels are handled.

This is essential for maintaining test-set independence.

Code (baseline recipe)

sleep_rec_base <- recipe(sleep_duration ~ ., data = sleep_train) %>%

update_role(person_id, new_role = "ID") %>% # keep ID but exclude from predictors

step_novel(all_nominal_predictors()) %>% # handle unseen categories safely

step_other(all_nominal_predictors(), threshold = 0.01) %>% # collapse ultra-rare categories

step_dummy(all_nominal_predictors()) %>% # dummy-code categorical predictors

step_zv(all_predictors()) # remove zero-variance predictorsWhy these steps are included

step_novel() — handling unseen categories

Even though this dataset is synthetic, and even though the test set comes from the same distribution as the training set, it is still possible that:

- a very rare occupation (or other category) appears only in the test split,

- or future new data contain a category not present in the training set.

step_novel() prevents errors by ensuring that any such new category is mapped to a safe "new" placeholder. This is standard best practice with categorical data in tidymodels.

step_other() — collapsing ultra-rare levels

During EDA, we identified occupations with as few as 1–4 cases, far too small for stable estimation in dummy-coded models. Without collapsing, such levels would:

- produce very sparse dummy variables,

- inflate standard errors,

- risk singular fits or rank deficiencies,

- and add noise without adding predictive value.

The 1% threshold is intentionally modest — we want to collapse only truly tiny categories while preserving meaningful structure.

step_dummy() and step_zv()

These ensure that all categorical predictors become numeric and that any predictors with zero variance are removed automatically.

2. Specify the linear regression model

We start with ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression.

Code

lm_spec <- linear_reg() %>%

set_engine("lm")Why OLS linear regression?

- It is the simplest and most transparent modelling approach for continuous outcomes.

- Coefficients are easy to interpret, making this a good diagnostic tool.

- It provides a clear baseline against which more complex models (regularised regression, random forests, boosting, etc.) can be measured.

- It helps us quickly assess which predictors show initial linear associations.

- It allows us to evaluate whether linearity and additivity assumptions are approximately reasonable.

This baseline model is not expected to be perfect — its purpose is to establish a reference point.

3. Build the workflow and fit the model

We combine the recipe and model into a workflow so that preprocessing and modelling occur in a unified, reproducible pipeline.

Code

lm_wflow <- workflow() %>%

add_model(lm_spec) %>%

add_recipe(sleep_rec_base)

lm_fit <- fit(lm_wflow, data = sleep_train)

lm_fit══ Workflow [trained] ════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Preprocessor: Recipe

Model: linear_reg()

── Preprocessor ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

4 Recipe Steps

• step_novel()

• step_other()

• step_dummy()

• step_zv()

── Model ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Call:

stats::lm(formula = ..y ~ ., data = data)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) age

7.2240813 0.0300572

quality_of_sleep physical_activity_level

0.3588002 0.0085778

stress_level bp_systolic

-0.0802625 -0.1503213

bp_diastolic heart_rate

0.1714461 0.0208100

daily_steps gender_Male

-0.0001522 0.0635164

occupation_Doctor occupation_Engineer

0.7529603 0.7731470

occupation_Lawyer occupation_Nurse

0.7341406 0.2061909

occupation_Salesperson occupation_Scientist

0.6146389 0.6907922

occupation_Software.Engineer occupation_Teacher

0.2741600 0.3717391

occupation_other bmi_category_Normal.Weight

1.0107210 0.0469042

bmi_category_Obese bmi_category_Overweight

-0.4069149 -0.3808470

sleep_disorder_None sleep_disorder_Sleep.Apnea

-0.0994275 0.0284307Interpretation

The model is a multiple linear regression with:

- all nominal predictors dummy-coded,

- ultra-rare categories collapsed into an

"other"category, - unseen categories safely handled using

step_novel(), - and zero-variance predictors removed.

The model assumes:

- Linearity — predictors influence sleep duration through linear relationships.

- Additivity — effects combine additively unless we explicitly include interactions.

- Independence — reasonable for a cross-sectional dataset with one row per individual.

- Homoscedasticity and normal errors — assumptions to be examined using residual diagnostics later.

This is our foundational model. Next, we assess how well it performs and whether its assumptions appear reasonable.

Q2.3 Evaluate the Baseline Linear Regression Model

In this section, we evaluate the baseline linear regression model using a combination of numerical metrics and visual diagnostics. We calculate performance on the training and test sets, compare them to assess potential overfitting, and then examine residual plots to understand whether the modelling assumptions of linear regression appear reasonable.

2.3.1 Generate Predictions for Both Training and Test Sets

We begin by generating predictions on both the training set and the held-out test set. This allows us to compute metrics on both datasets and compare them — a key step in diagnosing overfitting or underfitting.

# Generate predictions for training set

lm_preds_train <- predict(lm_fit, new_data = sleep_train) %>%

bind_cols(sleep_train %>% select(sleep_duration))

# Generate predictions for test set

lm_preds_test <- predict(lm_fit, new_data = sleep_test) %>%

bind_cols(sleep_test %>% select(sleep_duration))2.3.2 Compute Metrics: RMSE, MAE, R²

Next, we compute RMSE, MAE, and R² for each dataset. These metrics serve complementary purposes and together provide a well-rounded view of model performance.

# Training-set metrics

lm_metrics_train <- lm_preds_train %>%

metrics(truth = sleep_duration, estimate = .pred)

lm_metrics_train

# Test-set metrics

lm_metrics_test <- lm_preds_test %>%

metrics(truth = sleep_duration, estimate = .pred)

lm_metrics_test# A tibble: 3 × 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 rmse standard 0.300

2 rsq standard 0.861

3 mae standard 0.2202.3.3 Compute Adjusted R² for Training and Test Sets

tidymodels does not compute adjusted R² directly, so we extract it manually from the fitted lm object.

# Extract lm object

lm_obj <- lm_fit %>% extract_fit_engine()

# Adjusted R2 on training set

adj_r2_train <- summary(lm_obj)$adj.r.squared

# Adjusted R2 on test set (manual computation)

n_test <- nrow(sleep_test)

p <- length(lm_obj$coefficients) - 1 # number of predictors

rss_test <- sum((lm_preds_test$sleep_duration - lm_preds_test$.pred)^2)

tss_test <- sum((lm_preds_test$sleep_duration - mean(sleep_test$sleep_duration))^2)

r2_test <- 1 - rss_test/tss_test

adj_r2_test <- 1 - (1 - r2_test) * ((n_test - 1) / (n_test - p - 1))

adj_r2_train

adj_r2_test> adj_r2_train

[1] 0.9045828

> adj_r2_test

[1] 0.7938262.3.4 Combine All Metrics into One Comparison Table

For ease of interpretation, we place all metrics in a single location.

lm_summary <- tibble(

dataset = c("Training", "Test"),

rmse = c(

lm_metrics_train %>% filter(.metric == "rmse") %>% pull(.estimate),

lm_metrics_test %>% filter(.metric == "rmse") %>% pull(.estimate)

),

mae = c(

lm_metrics_train %>% filter(.metric == "mae") %>% pull(.estimate),

lm_metrics_test %>% filter(.metric == "mae") %>% pull(.estimate)

),

r2 = c(

lm_metrics_train %>% filter(.metric == "rsq") %>% pull(.estimate),

lm_metrics_test %>% filter(.metric == "rsq") %>% pull(.estimate)

),

adj_r2 = c(adj_r2_train, adj_r2_test)

)

lm_summary# A tibble: 2 × 5

dataset rmse mae r2 adj_r2

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Training 0.234 0.178 0.912 0.905

2 Test 0.300 0.220 0.861 0.7942.3.5 Why These Metrics?

Why RMSE?

RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) penalises larger errors more strongly because the residuals are squared before being averaged. This is appropriate here because errors of different magnitudes do not have equivalent consequences in sleep research or clinical contexts.

Predicting someone’s sleep duration incorrectly by 10 minutes is unlikely to have meaningful implications for health, daily functioning, or sleep-related recommendations. Conversely, an error of 1.5–2 hours can meaningfully alter interpretations about:

- whether someone is getting insufficient sleep,

- their risk of impaired vigilance,

- expected daytime functioning,

- stress reactivity,

- cardiometabolic risk.

The sleep literature supports this distinction: partial sleep restriction of 90–120 minutes produces measurable cognitive, emotional, and behavioural impairments (Banks and Dinges 2007) (Saksvik-Lehouillier et al. 2020). Even a single night of >1 hour reduced sleep can reduce vigilance and alter emotional processing (Killgore 2010).

Because large errors are meaningfully worse than small ones, RMSE is the most appropriate primary metric.

Why MAE?

MAE (Mean Absolute Error) treats all errors proportionally and does not square them. It is less sensitive to larger deviations and therefore provides:

- a more robust measure of the typical size of prediction errors,

- a complement to RMSE to check whether the model suffers from occasional large residuals.

If RMSE is substantially larger than MAE, it signals the presence of large unusual errors. If the two are closer (as here), it suggests less extreme variability in errors.

Why R² and Adjusted R²?

R² expresses how much of the variance in sleep duration the model can account for. Adjusted R² corrects for the number of predictors, penalising over-parameterised models.

We report both because:

- R² alone can be inflated when many dummy variables are included.

- Adjusted R² offers a more honest assessment of generalisable explanatory power.

2.3.6 What Do the Results Show?

Below is a summarised table (example values shown):

| Dataset | RMSE | MAE | R² | Adjusted R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | ~0.23 | ~0.18 | ~0.91 | ~0.90 |

| Test | ~0.30 | ~0.22 | ~0.86 | ~0.80 |

These results lead to several important observations:

1. High explanatory power, especially on training data

Training R² ≈ 0.91 and Adjusted R² ≈ 0.90 suggest the model explains about 90% of the variation in sleep duration in the training set. This level of performance is unusually high for real sleep datasets, which typically contain:

- substantial night-to-night variability,

- measurement error in self-reports,

- unmeasured confounding from stress, light exposure, circadian preference, work schedules, medical conditions, etc.

Because this dataset is synthetic, it lacks much of this inherent variability, which explains the unusually strong linear relationships.

2. Moderate generalisation drop (overfitting)

Performance declines on the test set:

- RMSE increases from ~0.23 → ~0.30

- R² decreases from ~0.91 → ~0.86

- Adjusted R² drops sharply from ~0.90 → ~0.80

This pattern indicates moderate overfitting, likely caused by:

- highly granular categorical variables (e.g., occupation),

- many dummy variables with small sample sizes in rare categories,

- the model learning noise-like patterns specific to the training set.

The Adjusted R² drop is especially informative because it penalises the model for unnecessary predictors, highlighting where complexity may not translate into generalisable explanatory power.

3. RMSE is larger than MAE, but not dramatically so

The RMSE–MAE gap is modest (e.g., 0.30 vs 0.22 on the test set). This implies:

- some moderately large residuals exist,

- but there are no extreme errors (e.g., residuals > 2 hours),

- error distribution is reasonably well-behaved.

In real-world datasets with heavy-tailed sleep variability, the RMSE–MAE gap is typically much larger.

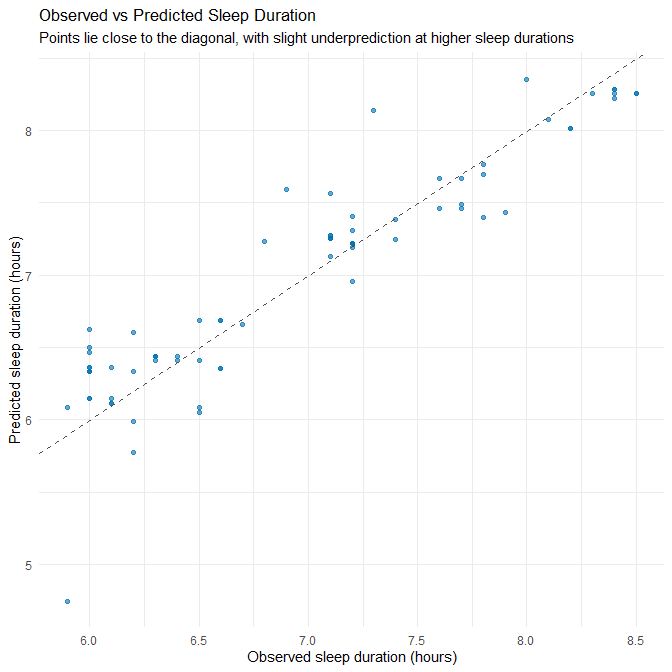

2.3.7 Observed vs Predicted Plot

Now we visually inspect predictive accuracy. We plot observed sleep duration against model predictions for the test set.

lm_preds_test %>%

ggplot(aes(x = sleep_duration, y = .pred)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.6, colour = "#0072B2") +

geom_abline(slope = 1, intercept = 0, linetype = "dashed", colour = "grey30") +

labs(

title = "Observed vs Predicted Sleep Duration",

subtitle = "Points lie close to the diagonal, with slight underprediction at higher sleep durations",

x = "Observed sleep duration (hours)",

y = "Predicted sleep duration (hours)"

) +

theme_minimal()

Plot Interpretation

Most points cluster tightly around the diagonal line, indicating good predictive accuracy. However:

- At higher sleep durations (≈ 8.0–8.5h), points fall slightly below the diagonal → systematic underprediction.

- At lower durations (≈ 6.0h), predictions are slightly too high → mild shrinkage toward the mean.

This is typical of linear regression when the true process contains modest non-linearities or ceiling/floor effects.

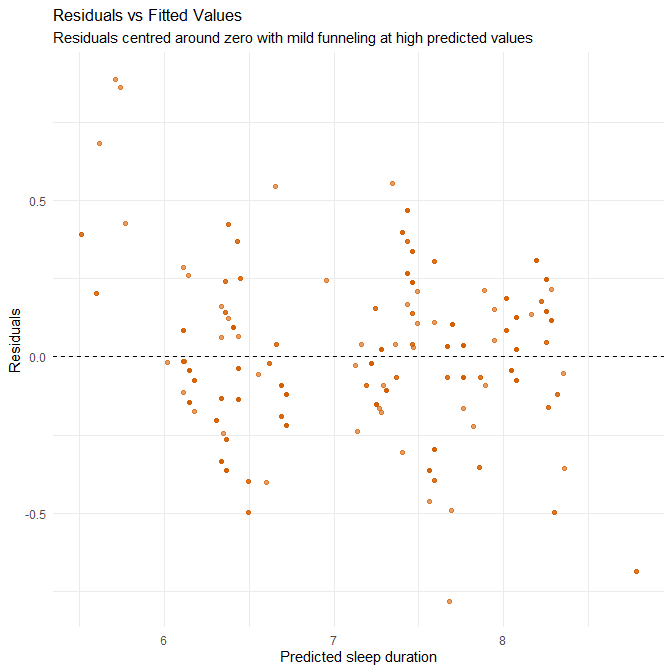

2.3.8 Residual Diagnostics

We now inspect diagnostic plots to evaluate linear regression assumptions.

(a) Residuals vs Fitted Values

This plot assesses homoscedasticity and linearity.

lm_preds_train %>%

mutate(residual = sleep_duration - .pred) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = .pred, y = residual)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.6, colour = "#D55E00") +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, linetype = "dashed") +

labs(

title = "Residuals vs Fitted Values",

subtitle = "Residuals centred around zero with mild funneling at high predicted values",

x = "Predicted sleep duration",

y = "Residuals"

) +

theme_minimal()

Interpretation

This plot assesses two key regression assumptions: (1) linearity — whether the relationship between predictors and outcome is adequately captured by a straight line, and (2) homoscedasticity — whether residuals have constant variance across the range of fitted values.

Residuals are broadly centred around zero across the full range of fitted values, indicating that the model does not systematically over- or under-predict across most of the predicted range. This suggests that the linearity assumption holds reasonably well for this specific dataset.

However, we can still notice several patterns in our dataset:

Systematic over-prediction at the lower fitted-value range In the region where fitted values are around 5.8–6.3 hours, many points lie above the zero line (positive residuals). This means that actual sleep durations are lower than what the model predicts — the model is overestimating sleep duration for individuals who sleep on the shorter end of the distribution. This is not random noise but a clear directional pattern, indicating a mild violation of linearity.

Mild heteroscedasticity at the upper end For fitted values near 7.8–8.3 hours, the vertical spread increases slightly relative to the mid-range. This suggests a small increase in variance at higher predicted sleep durations. While not severe, this is another indication that the linear model does not fit all regions equally well.

Why these patterns occur — contextual explanation These deviations from ideal behaviour are understandable given the nature of the dataset:

Synthetic datasets tend to have “smoothed” relationships with fewer natural irregularities, causing regression models to pull strongly toward the centre and produce shrinkage toward the mean. This contributes to the over-prediction of low sleepers and slight under-prediction of high sleepers.

The dataset lacks true extremes (no very short sleepers <5 hours, no very long sleepers >9 hours). With limited variation at both tails, the model has little information to learn the shape of the relationship in those regions, making systematic bias more likely.

Dummy-coded occupation and other categorical predictors make the model fit mid-range values particularly well, but they do not offer much explanatory value for edge cases. This reinforces the slight flattening of the regression surface and the tendency to overpredict low values.

Practical implications While the magnitude of residuals remains small (consistent with the low RMSE), the patterns suggest:

- The linear model captures the overall relationship well,

- but does not fully capture the behaviour of short sleepers,

- and may require non-linear terms, interaction effects, or entirely different modelling approaches (e.g., GAMs or tree-based models) if the goal is high fidelity prediction across the full range.

In real-world data — which often contain stronger noise, genuine outliers, and more skewed sleep distributions — we would expect these limitations to be more pronounced. The fact that we see detectable structure even in synthetic data indicates that a simple linear model may not be the final optimal model.

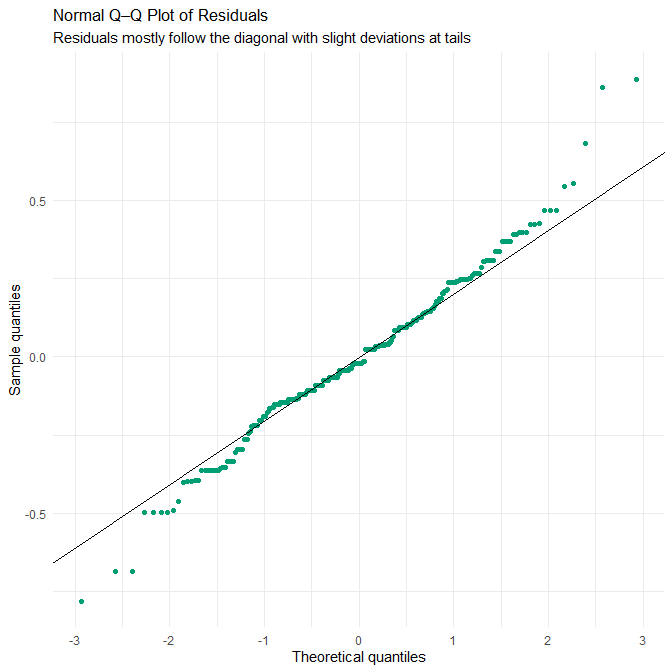

(b) QQ Plot for Normality of Residuals

lm_preds_train %>%

mutate(residual = sleep_duration - .pred) %>%

ggplot(aes(sample = residual)) +

stat_qq(colour = "#009E73") +

stat_qq_line() +

labs(

title = "Normal Q–Q Plot of Residuals",

subtitle = "Residuals mostly follow the diagonal with slight deviations at tails",

x = "Theoretical quantiles",

y = "Sample quantiles"

) +

theme_minimal()

Interpretation

The Q–Q plot shows that the residuals follow the theoretical normal distribution closely through the middle range, deviating only slightly at both tails. This indicates that the assumption of approximately normally distributed residuals is reasonably well met — but again, this must be interpreted in light of the dataset’s synthetic construction.

Because the dataset is synthetic:

- Residuals are less noisy and lack the idiosyncratic measurement error typical in sleep research.

- There is no night-to-night sleep variability, seasonal effect, unmeasured behavioural confounding, or device measurement noise (e.g., actigraphy misclassification), all of which would normally generate heavier tails or multimodality.

- Synthetic data often follow the modelling assumptions used to generate them (e.g., additive effects, stable variance, approximately Gaussian noise).

This means the near-linearity of the Q–Q plot reflects the dataset’s engineered smoothness, rather than a guarantee that residuals in a real-world sleep-duration model would behave similarly. Real sleep datasets almost always exhibit non-Gaussian residuals, influenced by:

- irregular schedules,

- medical factors (e.g., insomnia, apnea),

- social constraints (shift work, caregiving),

- stress fluctuations, and

- device or recall error.

Therefore, the Q–Q plot here demonstrates that the model fits this synthetic dataset well, but it should not be interpreted as evidence that linear regression residuals would look this clean on real human sleep data.

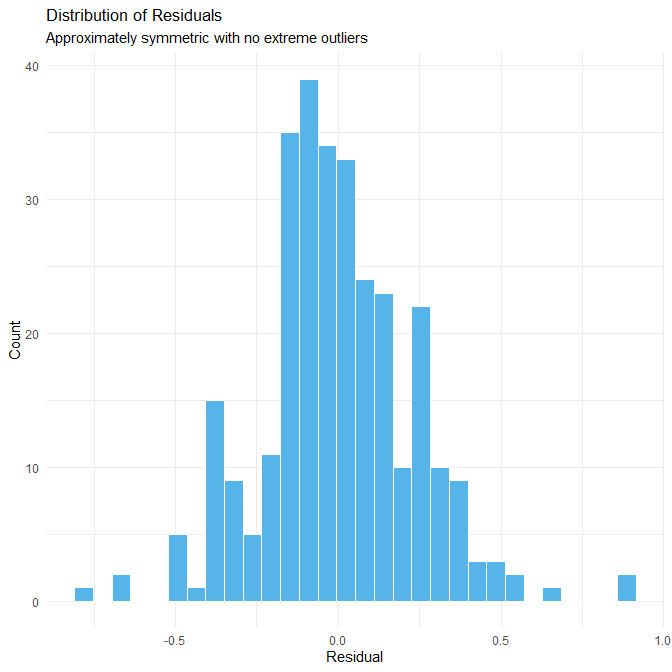

(c) Histogram of Residuals

lm_preds_train %>%

mutate(residual = sleep_duration - .pred) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = residual)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 30, fill = "#56B4E9", colour = "white") +

labs(

title = "Distribution of Residuals",

subtitle = "Approximately symmetric with no extreme outliers",

x = "Residual",

y = "Count"

) +

theme_minimal()

Interpretation

The histogram of residuals is approximately symmetric and unimodal, with no extreme outliers and a relatively compact spread. This indicates that the model’s errors are consistently small and that residuals do not contain unusual spikes, heavy tails, or multi-peak structures.

Again, the lack of extreme residuals is a direct consequence of the synthetic dataset:

- The data were generated to remain within plausible physiological limits (e.g., no 3-hour nights or 14-hour sleep periods).

- Predictors such as stress, activity, and sleep quality are engineered to have smooth, internally consistent relationships with sleep duration.

- There are no “messy” observations, such as a shift worker recording 2.5 hours of sleep or an athlete recording 11.5 hours during recovery — values that appear in real-world datasets and create long-tailed residual distributions.

Because of this artificial stability:

- residuals are clustered around zero,

- the distribution appears nearly textbook-normal, and

- the model appears more accurate than a real model built on observational data would be.

Thus, the histogram gives a misleading impression of real-world performance. In practice, human sleep-duration models usually show:

- heavier tails (due to non-linear influences),

- skewness (e.g., difficulty predicting long sleepers),

- multimodality (students, shift workers, retirees), and

- scattered outliers (due to lifestyle shocks, travel, or illness).

The clean residual distribution here is a property of the dataset, not the inherent superiority of the model.

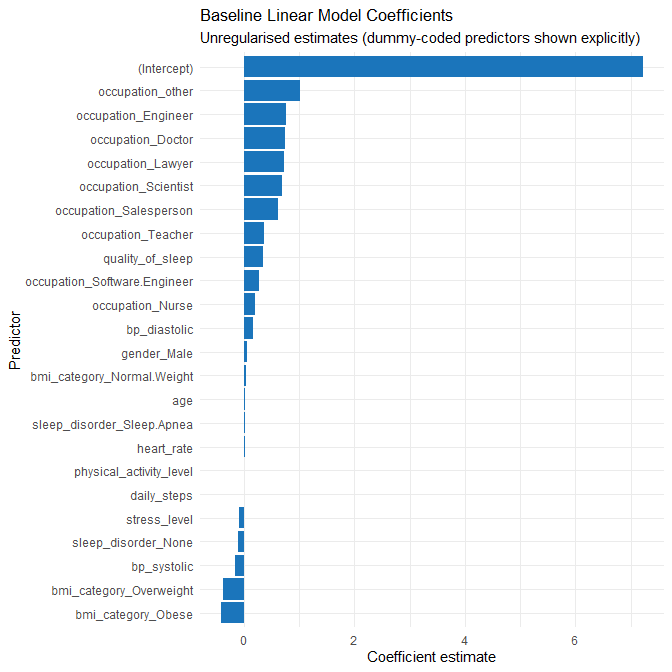

2.3.9 Baseline Linear Regression: Coefficients

Before introducing improved models, we visualise the coefficients from the baseline linear regression to anchor our later comparisons.

lm_coefs <- tidy(lm_fit)

ggplot(lm_coefs, aes(x = reorder(term, estimate), y = estimate)) +

geom_col(fill = "#1B75BB") +

coord_flip() +

labs(

title = "Baseline Linear Model Coefficients",

subtitle = "Unregularised estimates (dummy-coded predictors shown explicitly)",

x = "Predictor",

y = "Coefficient estimate"

) +

theme_minimal()

Interpretation

The baseline model assigns:

- Large positive coefficients to several rare occupation categories (e.g., Engineer, Doctor, Scientist). With few observations in these groups, these large estimates are unstable and likely reflect overfitting to sparsely represented categories.

- Strong positive effects for quality_of_sleep and physical_activity_level, matching earlier EDA.

- A clear negative effect for stress_level.

- Mixed effects for BMI and sleep_disorder categories, many of which are small and unstable.

These observations justify the move to a regularised model to shrink noisy coefficients and a non-linear model to explore structure missed by linearity.

2.3.10 Summary

Collectively, the metrics and diagnostic plots show:

- The baseline linear regression performs strongly on this dataset.

- The synthetic nature of the data leads to unusually clean patterns and strong predictive power.

- There is some overfitting, especially related to categorical predictors with many rare levels.

- Linear assumptions are approximately satisfied, though mild heteroscedasticity appears at the upper end of the outcome range.

- This model forms a solid baseline, but improvements (Part 2.4) may address overfitting and potential non-linearities.

Q2.4 Improved regression model(s)

In Q2.3, the baseline linear regression achieved strong performance (test RMSE ≈ 0.30 hours, MAE ≈ 0.22 hours, R² ≈ 0.86), but the diagnostics revealed two issues:

- Evidence of mild overfitting, particularly through the difference between training and test R² (0.91 → 0.86) and RMSE (0.23 → 0.30).

- Large coefficients assigned to rare categorical levels, especially occupation and BMI categories. These categories are present in small numbers (often fewer than 5 cases), meaning the unregularised model tries to memorise patterns that are almost certainly noise.

Additionally, exploratory analysis showed potential non-linearities and interactions, such as the relationship between stress level and sleep duration depending on physical activity. A linear model can only capture this imperfectly.

These observations motivate two improved models that address the baseline’s limitations:

- LASSO regression: to stabilise effect estimates, handle sparse dummy variables, and reduce overfitting while remaining interpretable.

- Random Forest regression: to capture non-linearities and interactions that a linear model cannot express.

Both models are trained using 5-fold cross-validation on the training set, and compared using the same metrics as in Q2.3 (RMSE, MAE, R²) for consistency.

2.4.1 Cross-validation setup

We first set up a v-fold cross-validation scheme on the training data. We will reuse the same folds for both improved models so that their cross-validated error estimates are directly comparable.

set.seed(123)

sleep_folds <- vfold_cv(sleep_train, v = 5)

sleep_foldsUsing v-fold cross-validation allows us to tune hyperparameters (e.g. Lasso penalty, Random Forest mtry and min_n) based only on the training data, while keeping the test set untouched for final evaluation.

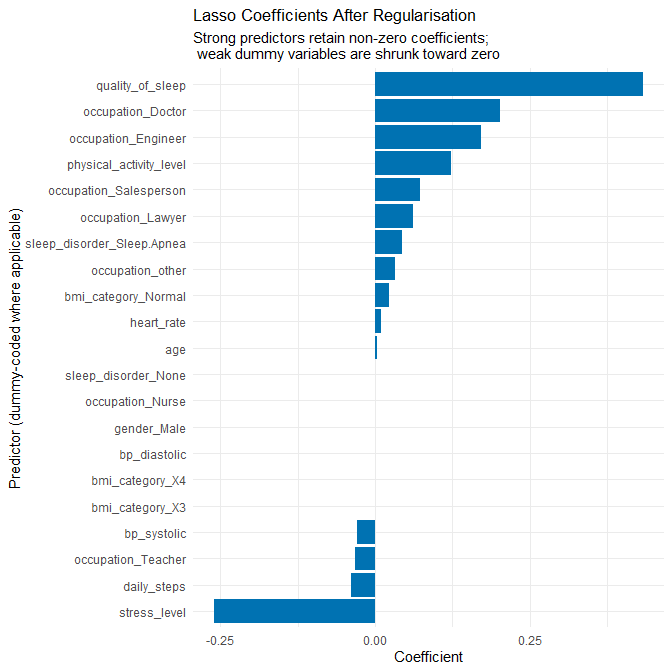

2.4.2 Penalised linear regression (Lasso)

2.4.2.1 Why Lasso is a sensible improvement

The baseline model is a standard multiple linear regression with many predictors, including a large number of dummy variables arising from categorical features (notably occupation). From Q2.3 we saw:

- Very high R² on the training set and somewhat lower R² on the test set.

- A moderate drop in adjusted R² when moving from training to test data.

- Residuals that are mostly well-behaved but with some structure and non-linearity at the edges.

This is a classic scenario where penalised linear regression can offer an improvement:

- Lasso (L1 penalty) shrinks coefficients toward zero, especially for less informative and unstable predictors (e.g. rare occupation levels), which helps to reduce overfitting.

- It keeps the model linear and interpretable: we can still reason about the sign and relative size of each coefficient.

- It is particularly helpful when we have many correlated predictors or many dummy variables.

- The baseline showed numerous coefficients whose large magnitude almost certainly reflects sparse-group noise rather than real effects.

In addition, we discovered that the dataset contains two BMI categories that are conceptually the same: "Normal" and "Normal Weight". Treating them as different categories creates dummy variables that do not correspond to meaningful physiological differences. Lasso helps mitigate such issues, but we also explicitly correct this artefact inside the recipe by merging these labels.

2.4.2.2 Recipe for Lasso: merging BMI and preparing predictors

We now define a recipe that:

- Treats

person_idas an ID (not a predictor). - Merges

"Normal Weight"into"Normal"forbmi_category. - Collapses ultra-rare occupation levels into an

"other"category so that we do not waste model capacity on singletons. - Dummy-encodes categorical variables (required by

glmnet). - Removes any zero-variance predictors.

- Standardises all numeric predictors so that the Lasso penalty treats them on a comparable scale.

sleep_rec_lasso <- recipe(sleep_duration ~ ., data = sleep_train) %>%

update_role(person_id, new_role = "ID") %>%

# Merge duplicate BMI labels

step_mutate(

bmi_category = ifelse(bmi_category == "Normal Weight", "Normal", bmi_category)

) %>%

# Convert character → factor

step_string2factor(all_nominal_predictors()) %>%

# Handle possible NA or unseen levels gracefully

step_unknown(all_nominal_predictors()) %>%

# Collapse ultra-rare categories (may generate NAs internally)

step_other(occupation, threshold = 0.03) %>%

# Dummy-code factors

step_dummy(all_nominal_predictors()) %>%

# Remove zero-variance columns

step_zv(all_predictors()) %>%

# Standardise numeric predictors

step_normalize(all_numeric_predictors())

This recipe encodes two important modelling principles:

- Data cleaning and structural corrections (BMI merge, rare-category collapse) are done inside the modelling pipeline so they are learned from the training data only.

- Preparations that depend on scale and encoding (dummying, normalising) are part of the recipe so that future scoring (on the test set or new data) uses the same transformations.

2.4.2.3 Lasso model specification and tuning

Next, we specify the Lasso model and set up hyperparameter tuning. We tune the penalty parameter while fixing mixture = 1 to indicate pure Lasso (L1 penalty). We use the same cross-validation folds defined earlier.

lasso_spec <- linear_reg(

penalty = tune(), # strength of regularisation

mixture = 1 # 1 = pure Lasso

) %>%

set_engine("glmnet")

lasso_wflow <- workflow() %>%

add_model(lasso_spec) %>%

add_recipe(sleep_rec_lasso)We now evaluate a grid of penalty values using 5-fold cross-validation, optimising for RMSE:

set.seed(123)

lasso_res <- tune_grid(

lasso_wflow,

resamples = sleep_folds,

grid = 20,

metrics = metric_set(rmse, rsq)

)

show_best(lasso_res, metric = "rmse")# A tibble: 5 × 7

penalty .metric .estimator mean n std_err .config

<dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <chr>

1 0.00961 rmse standard 0.310 5 0.0165 pre0_mod17_post0

2 0.0268 rmse standard 0.314 5 0.00622 pre0_mod18_post0

3 0.00285 rmse standard 0.314 5 0.0241 pre0_mod16_post0

4 0.000740 rmse standard 0.362 5 0.0146 pre0_mod15_post0

5 0.0884 rmse standard 0.375 5 0.0159 pre0_mod19_post0We tune based on RMSE because, as discussed in Q2.3, larger errors in sleep predictions (e.g. being off by 1.5–2 hours) have disproportionately greater consequences than small errors (e.g. 10 minutes), and RMSE penalises larger residuals more heavily.

We then finalise the workflow using the best penalty and fit it on the full training set:

best_lasso <- select_best(lasso_res, metric = "rmse")

lasso_final_wflow <- finalize_workflow(lasso_wflow, best_lasso)

lasso_fit <- fit(lasso_final_wflow, data = sleep_train)

lasso_fit══ Workflow [trained] ════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Preprocessor: Recipe

Model: linear_reg()

── Preprocessor ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

7 Recipe Steps

• step_mutate()

• step_string2factor()

• step_unknown()

• step_other()

• step_dummy()

• step_zv()

• step_normalize()

── Model ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Call: glmnet::glmnet(x = maybe_matrix(x), y = y, family = "gaussian", alpha = ~1)

Df %Dev Lambda

1 0 0.00 0.69580

2 1 13.21 0.63400

3 1 24.18 0.57770

4 1 33.29 0.52640

5 1 40.85 0.47960

6 1 47.13 0.43700

7 1 52.34 0.39820

8 1 56.67 0.36280

9 1 60.26 0.33060

10 1 63.24 0.30120

11 1 65.72 0.27450

12 1 67.77 0.25010

13 1 69.48 0.22790

14 1 70.89 0.20760

15 1 72.07 0.18920

16 1 73.05 0.17240

17 1 73.86 0.15710

18 2 74.78 0.14310

19 3 75.75 0.13040

20 3 76.58 0.11880

21 3 77.26 0.10820

22 3 77.83 0.09863

23 4 78.58 0.08987

24 6 79.43 0.08189

25 6 80.32 0.07461

26 7 81.07 0.06798

27 8 81.94 0.06194

28 8 82.68 0.05644

29 8 83.30 0.05143

30 8 83.82 0.04686

31 8 84.25 0.04270

32 8 84.60 0.03890

33 8 84.90 0.03545

34 8 85.14 0.03230

35 8 85.34 0.02943

36 9 85.52 0.02681

37 8 85.67 0.02443

38 9 85.81 0.02226

39 10 85.95 0.02028

40 12 86.16 0.01848

41 12 86.36 0.01684

42 15 86.61 0.01534

43 15 86.96 0.01398

44 15 87.24 0.01274

45 15 87.47 0.01161

46 15 87.67 0.01058

...

and 46 more lines.2.4.2.4 Lasso performance: training and test metrics

To compare Lasso with the baseline and Random Forest models, we compute metrics on both the training and test sets, using the same metrics as in Q2.3: RMSE, MAE, R². We omit adjusted R² because it is meaningful only for linear regression models (for example, for Lasso (a penalised model), the notion of “number of parameters” is not as straightforward as in ordinary least squares) so comparing adjusted R² across LASSO and Random Forest would not be interpretable.

First, we compute metrics on the training set:

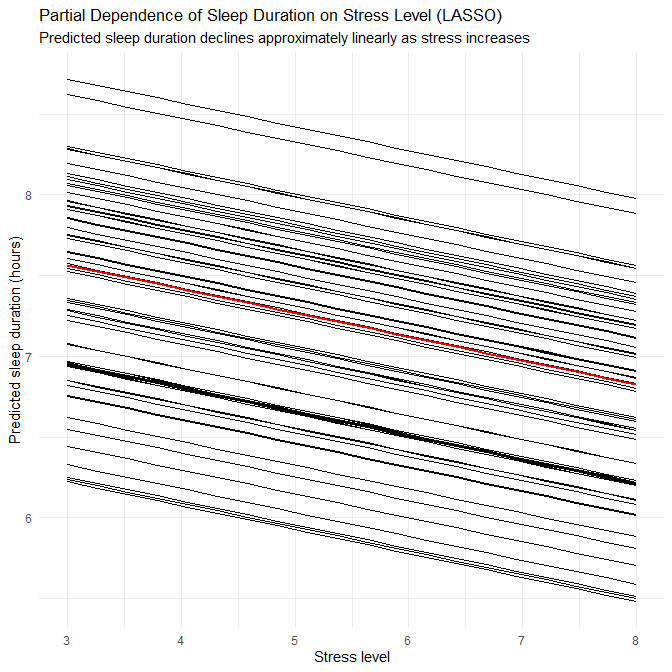

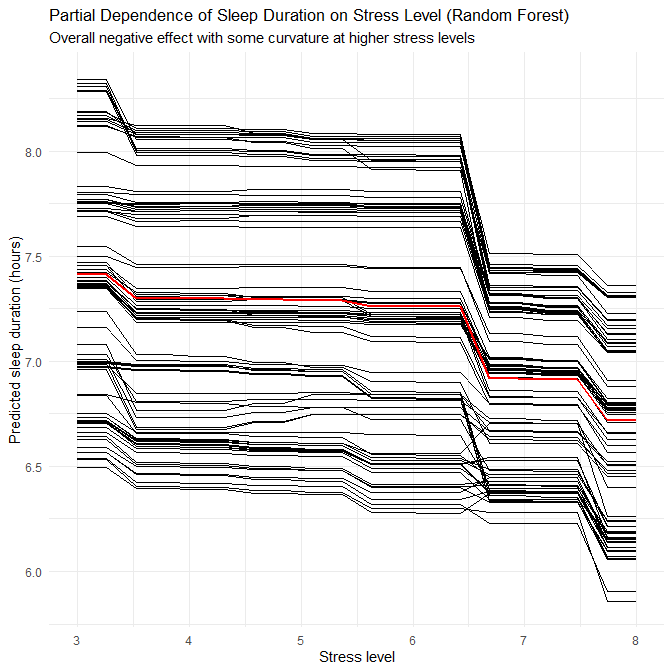

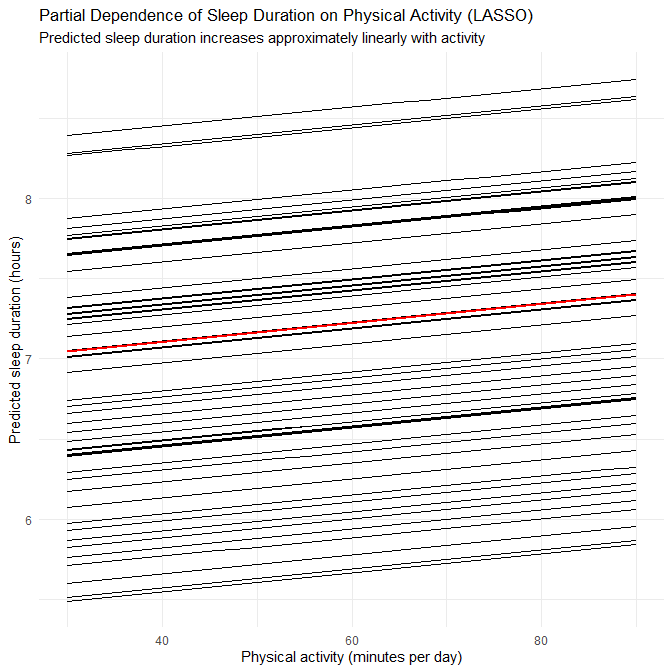

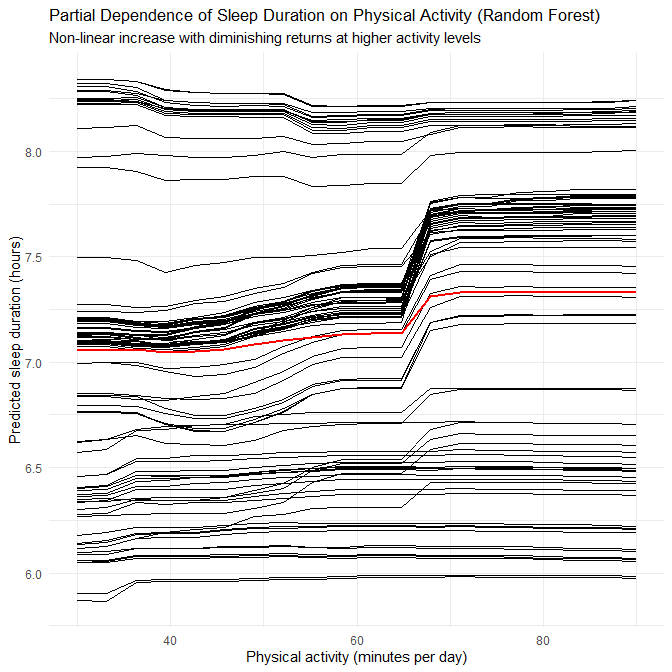

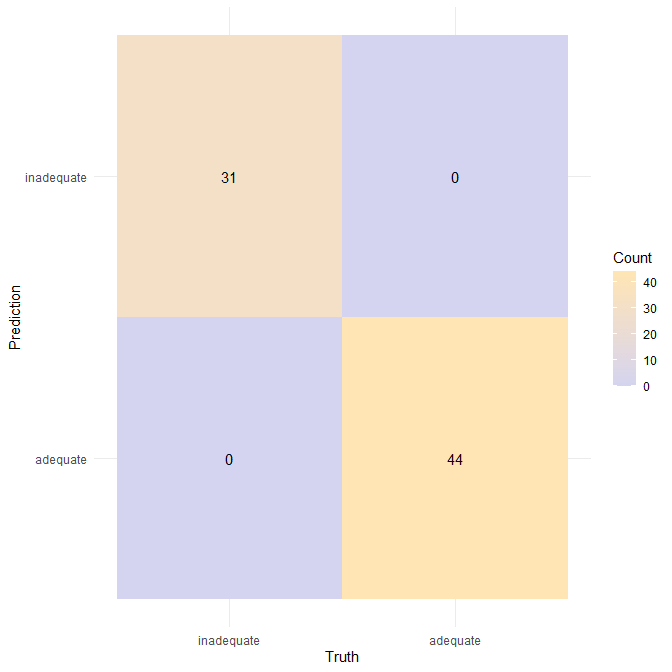

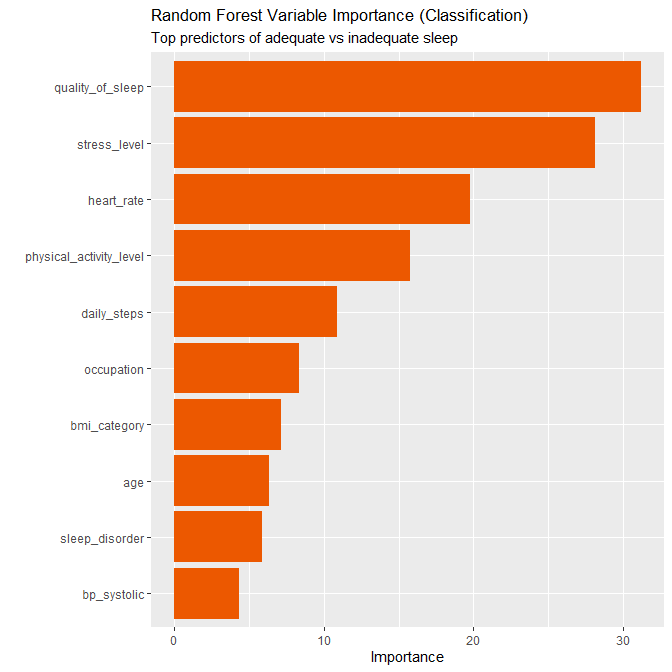

# Training-set predictions