Week 05

Data Transformation and Visualisation Design

DS105A – Data for Data Science

🗓️ 30 Oct 2025

Today’s Goals

- Learn: Custom functions and the

.apply()method

- Master: DateTime operations and temporal grouping

- Discover: Why summarisation makes patterns visible

- Practice: The

plot_dfpattern for seaborn visualisation

Why this matters: These skills directly support your ✍️ Mini-Project 1 work.

1️⃣ From Loops to Functions

In the 💻 W04 Lab, you explored nested np.where() when classifying weather attributes like temperature and rainfall.

Today, we’ll solve that same problem with a different (cleaner) approach: custom functions and the .apply() method.

The Problem We’re Solving

The task was to classify weather based on temperature and rainfall into the following categories:

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Hot & Dry | temperature > 25°C and rainfall < 1mm |

| Hot & Wet | temperature > 25°C and rainfall >= 1mm |

| Mild & Dry | temperature in 20-25°C and rainfall < 1mm |

| Mild & Wet | temperature in 20-25°C and rainfall >= 1mm |

| Cool | temperature < 20°C and rainfall any |

What if…

Instead of using nested np.where(), I could just more naturally say:

and get this as a response:

(a single normal string)

Such that I could apply this to every combination of temperature and rainfall I have in my dataset?

In the olden days…

We don’t do for loops anymore 🙃

Back in the days where we used for loops and separate lists/arrays, this would look like this:

Nice!

In the age of pandas…

If we had such a way to classify weather, we could use vectorised operations in pandas to classify weather for every row in our dataset in a single line of code (instead of a for loop).

What is a function?

It’s a reusable block of code that takes inputs and produces an output. You can invoke it by calling its name with the appropriate inputs.

How to define a function:

Key components:

def: defines a function

- Function name: you choose a descriptive and clear name

- Parameters: are the inputs to the function

- Docstring explains what it does

returnproduces the output

Functions Make Logic Testable

You always test a function on single values first.

Why test first? Easier to debug a function than nested np.where()!

From loops to functions

The

.apply()method inpandasallows you to apply a function to every element in a Series.It works kind of like a

forloop, but cleaner and more efficient.It looks like this:

The output is a new pandas Series with the same index as the original Series.

That is, something like this:

Adding a new column to the DataFrame

If you assign the output of the

.apply()method to a new column in the DataFrame…using the

=operator:alternatively, you can use the

.assign()method:

- Either way, you would get a new column in the DataFrame with the results:

| date | temperature | is_hot |

|---|---|---|

| 2024-08-15 | 28 | True |

| 2024-08-16 | 22 | False |

| 2024-08-17 | 26 | True |

Filtering data (recap)

Last week, we talked about code that looked like this:

That is, you create a boolean array using a logical condition and then use it to filter the DataFrame.

By the way, sometimes I find it clearner to split this into two steps:

It makes it easier to read and debug.

Filtering data with .apply()

You can also use

.apply()to filter data.This is equivalent to the code we saw last week.

When to use which?

In this particular case, I think the first approach is easier to read and debug: df[df['temperature'] > 25].

This is because greater than (>) is a simple logical operation that is already vectorised and implemented in the pandas (and numpy) library.

- Make it a habit to search through the

pandasdocumentation to see if the operation you want to perform is already vectorised.

The two types of .apply()

- When you do

df[column].apply(function), you are applying the function to every element in the pandas Series. - But if you do

df.apply(function), you are applying the function to each dimension (row or column) in the DataFrame.

The two types of data in pandas

The two types of .apply() (continued)

When you do

df[column].apply(function), you are applying the function to every element in the pandas Series.But if you do

df.apply(function), you are applying the function to each dimension (row or column) in the DataFrame.You can specify an

axisargument to control which dimension you want to apply the function to.axis=0means “down the rows” (column-wise) andaxis=1means “across columns” (row-wise).

One-liners with lambda

Sometimes you just want a quick, inline function for a one-liner. Use lambda.

You can also combine with .assign() for method chaining:

When logic grows complex, prefer a named def function for readability and testing.

Comparing Approaches

Nested np.where() (W04 Lab):

Function + .apply() (Clean):

💭 Note: I used row as the parameter rather than the individual columns.

When to Use Functions

Extract functions when:

- Logic is complex (multiple conditions)

- You need to test edge cases

(lots ofif-elif-elsestatements)

- You’ll reuse the logic elsewhere

- Nested conditionals would become unreadable

Use built-in operations when:

- Logic is simple (one condition)

- Vectorised operations suffice

- Pandas/NumPy already has the operation 💡 Get used to searching the documentation. We can’t possibly teach you all the operations that are available in

pandasandnumpy.

Connecting to Your Work

You might need to use custom functions (def statements) and apply() in your ✍️ Mini-Project 1 either to filter data based on complex logic or to create classification labels.

2️⃣ Temporal Data

(A short intro)

To answer questions like “Is London’s air getting better or worse?” you need to:

- Work with

datetimeobjects - Extract date components (year, month)

- Aggregate data by date components to reveal patterns

DateTime Conversion

APIs typically return timestamps as Unix epoch (seconds since 1970):

Convert to datetime:

Now you get readable dates:

2021-10-01 00:00:00+00:00The .dt Accessor

Once you have datetime objects, you have superpowers!

You can extract components of the datetime object using the .dt accessor:

Before:

| date |

|---|

| 2024-08-15 |

| 2024-08-16 |

| 2024-08-17 |

After:

| date | year | month | day | dayofweek |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-08-15 | 2024 | 8 | 15 | 3 (Thursday) |

| 2024-08-16 | 2024 | 8 | 16 | 4 (Friday) |

| 2024-08-17 | 2024 | 8 | 17 | 5 (Saturday) |

Recommended readings

I really like this RealPython tutorial Using Python datetime to Work With Dates and Times. Give it a read!

Most of the features that exist in the Python default datetime module are also available in the pandas library.

This pandas documentation page is also a good resource.

☕ Coffee Break

After the break:

- The

groupby()method: split-apply-combine strategy - Simple data visualisation with seaborn

- The

plot_dfpattern: prepare data, then visualise

3️⃣ Split -> Apply -> Combine

Very often, we need to calculate summary statistics for groups of data instead of for the entire dataset.

For example, you might want to calculate the average temperature for each month in a year.

The groupby() method

The pandas library provides a method called groupby() to help you do precisely this:

Before (raw data):

| date | year | temperature |

|---|---|---|

| 2021-01-15 | 2021 | 5 |

| 2021-06-15 | 2021 | 22 |

| 2022-01-15 | 2022 | 6 |

| 2022-06-15 | 2022 | 24 |

What pandas will do:

- Separate the data into groups based on the

yearcolumn. - Calculate the

meanfor the entiretemperaturecolumn for each year. - Combine the results back together into a new DataFrame 👉

After:

| year | temperature |

|---|---|

| 2021 | 13.5 |

| 2022 | 15.0 |

GroupBy Fundamentals

Basic pattern:

Common aggregation functions:

.mean()- average.median()- middle value.sum()- total.max()- maximum.min()- minimum.count()- number of items

Method Chaining for Readability

When chaining multiple operations, split them across lines:

Why? Each operation is on its own line, making the transformation clear and debuggable.

Alternative (harder to read):

Temporal Grouping Examples

or, say:

You can group by multiple columns

Here is an example of grouping by (year, month) combination:

4️⃣ Our data viz philosophy

At this stage in the course, we only expect you to create simple line and bar plots but we do have expectations for:

- Which Python library you will use to create your visualisation (Seaborn is our adopted library)

- How you will prepare your data for visualisation

- How you will write the title of your visualisation (in a narrative style)

A simple line plot

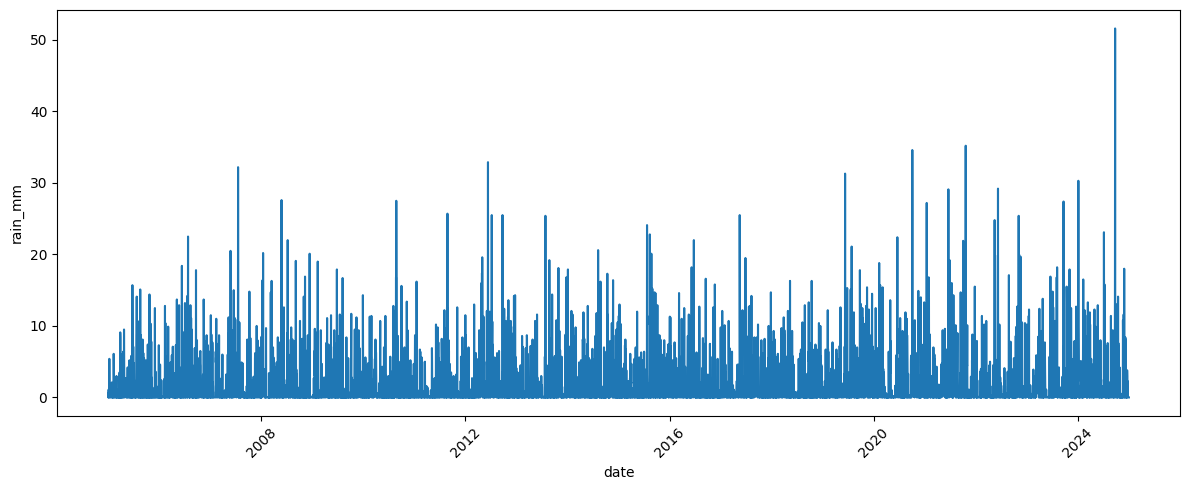

Provided you have a DataFrame plot_df which contains the columns date and rain_mm, this is the line that would produce a simple line plot:

How it would look like

🙃 Can you see why this plot is alright but not GREAT (as we want it to be in DS105)?

By the way, you need a few more lines of code

There’s the imports and config…

And the actual code to create the plot:

Why seaborn for DS105A

In this course, seaborn is our default because it forces you to think about your data as a table that has everything you need. You decide your variables (columns), build the table, then map columns to aesthetics.

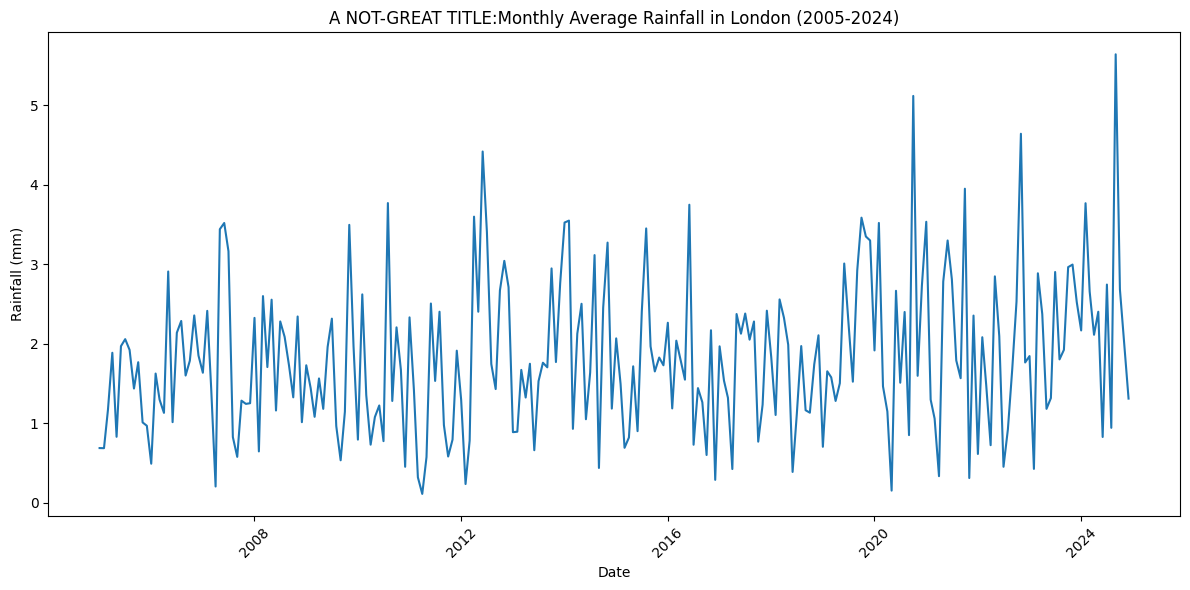

The plot_df Pattern

Let’s agree on a convention 🤝:

We will always create a plot_df first with all the columns we need for the visualisation and only then call matplotlib/seaborn.

Why? This way you can check if plot_df is correct before calling seaborn.

A plot from that plot_df would look like this:

This one shows an average value over time (aggregated by year+month).

Seaborn: Cheatsheet Approach

We won’t memorise all seaborn syntax. Instead:

- Know which plot type you need

- Feel free to use GenAI chatbots or master the relevant documentations for syntax

- Plot your prepared plot_df

Plot types:

sns.barplot(): Compare categories

sns.lineplot(): Show trends over time

sns.scatterplot(): Relationships between variables

sns.boxplot(): Distributions within groups

sns.heatmap(): Patterns across two dimensions

💡 For Mini-Project: You’ll have to create 2 insights. Choose plot types based on what pattern you’re showing.

Narrative Titles Matter

Bad title: “Temperature by Month”

Good title: “London summers are getting hotter”

The difference: Good titles state your finding, not describe what’s in the chart.

For Mini-Project 1: Each of your 2 insights needs a narrative title that communicates your analytical conclusion.

Questions?

Resources:

- 📓 Lecture notebook (downloadable)

- 💻 W05 Lab tomorrow

- 💬 Post questions in

#helpon Slack

- 📅 Attend drop-in sessions

Looking ahead: Week 06 (Reading Week) is focus time for Mini-Project 1 completion.

![]()

LSE DS105A (2025/26)