🗓️ Week 01

Welcome to the Course + Python Foundations

DS105W – Data for Data Science

23 Jan 2025

Welcome to DS105W!

Course Lead

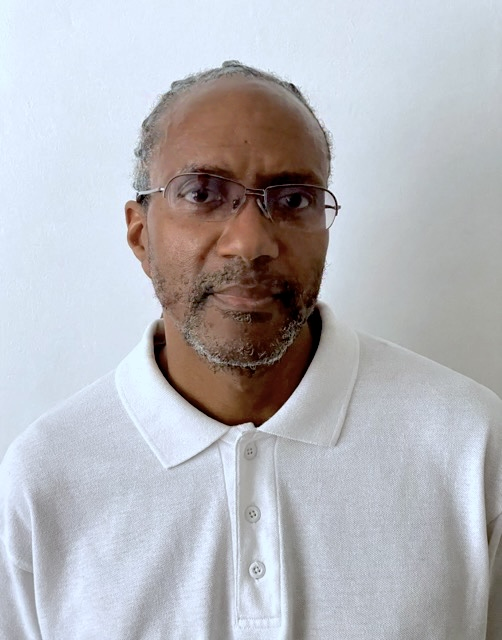

Dr Jon Cardoso-Silva 📧 @jonjoncardoso

Assistant Professor (Education)

LSE Data Science Institute

COURSE LEAD

Expertise & Current Projects

- PhD in Computer Science

- Experienced in software engineering, data science and data engineering

- Leading DS105 and DS205 course development

- Investigating the impact of GenAI impact on higher education (

![]() GENIAL project)

GENIAL project)

Recent Recognition:

LSESU Teaching Award for Feedback & Communication (2023)

Office Hours:

Thursdays, 11:00-13:00

Book via StudentHub

Teaching Support

Teaching Support

Administrative Support

Kevin Kittoe

Teaching & Assessment Administrator (DSI)

ADMINISTRATIVE SUPPORT

Contact 📧 DSI.ug@lse.ac.uk for:

- Course access issues

- Assignment submissions

- Extension requests

- Administrative queries

Key Information:

- All extension requests must follow LSE’s extension policy

- Email response time: 24-48 hours

- Include ‘[DS105W]’ in email subject lines

What can you expect to learn in DS105W?

Why this course exists?

🥅 Intended Learning Outcomes

| Outcome Category | What You’ll Master |

|---|---|

| Python Data Operations | • Apply Python and pandas to clean, reshape and transform raw data. • Implement data cleaning workflows. • Debug common data quality issues. |

| Data Collection | • Retrieve data from APIs. • Work with different file formats. |

| Data Analysis | • Design pandas analysis pipelines. • Construct multi-stage data transformations. • Evaluate data quality systematically. |

| Data Visualisation | • Create precise visualisations using lets-plot. • Apply Grammar of Graphics principles. • Analyse patterns through visual exploration. |

| Database Design | • Create normalised database schemas. • Integrate data from multiple sources. • Execute SQL queries effectively. |

| Version Control | • Use Git to track code changes. • Organise collaborative workflows. • Review and merge code systematically. |

✍️ Assessment Structure

| 20% | Individual | ✍️ Mini-project 1 |

Reveal: 14 February 2025 Due: 27 February 2025, 8pm |

| 30% | Individual | ✍️ Mini-project 2 |

Reveal: 3 March 2025 Due: 26 March 2025, 8pm |

| 10% | Group Work | 👥 Project Pitch |

Presentation Day: 4 April 2025 (during class) |

|

10%

30%

|

Group Work + Individual parts |

📦 Final Project |

Reveal: 25 March 2025 Due: 29 May 2025 |

Weekly formative exercises in Weeks 01-04 will prepare you for the summative assessments. These include hands-on practice with GitHub workflows and Python basics.

📑 Key Information

📟 Communication

Slack is our main point of contact. The invitation link will be available on Moodle.

- 📧 Email: Reserved for formal requests (extensions, appeals)

- 👥 Office Hours: Book via StudentHub

- 🆘 Drop-in Support: COL.1.06 (DSI Studio) - See calendar

Write code directly from the browser

We have a dedicated cloud environment on ![]() Nuvolos

Nuvolos

Visit the Nuvolos - First Time Access to learn how to get access to the DS105W environment.

Read the syllabus for week-by-week information on how we will cover the course content and assessments.

Let me ask you a few questions…

Coffee Break ☕

After the break:

How data is stored in a computer

Computers only understand 0s and 1s

Numbers, text, images, and sounds are all stored as sequences of 0s and 1s in your computer’s memory. Each 0 or 1 is called a bit.

Think of a bit is a tiny box:

\[ \require{color} \fcolorbox{black}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \phantom{\leftarrow \text{a bit can have a value of $0$}} \]

Computers only understand 0s and 1s

Numbers, text, images, and sounds are all stored as sequences of 0s and 1s in your computer’s memory. Each 0 or 1 is called a bit.

Think of a bit is a tiny box:

\[ \require{color} \begin{array}{ccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \leftarrow & \text{a bit can have a value of $0$} \end{array} \]

Computers only understand 0s and 1s

Numbers, text, images, and sounds are all stored as sequences of 0s and 1s in your computer’s memory. Each 0 or 1 is called a bit.

Think of a bit is a tiny box:

\[ \begin{array}{ccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \leftarrow & \text{OR it can have a value of $1$} \end{array} \]

but nothing else!

Boolean data type (aka bool)

For everything that has a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ answer, we can use a single bit.

\[ \textcolor{#9753b8}{\texttt{is_it_raining}} = \begin{cases} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{$\textcolor{black}{0}$} & \text{if it is not raining} \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \text{if it is raining} \end{cases} \]

In Python:

What about numbers?

Positive whole numbers

Suppose we want to represent positive numbers (0 included). We can’t do that with just a single bit!

With \(2\) bits, we can represent \(4\) different numbers:

\[\begin{array}{ccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 0 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 1 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 2 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 3 \\ \end{array}\]Positive whole numbers

With \(3\) bits, I can represent double the amount of numbers: \(8\)

\[\begin{array}{ccccccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 0 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 4 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 1 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 5 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 2 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 6 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 3 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 7 \\ \end{array}\]Positive whole numbers

With \(4\) bits, it doubles yet again and I can represent 16 different numbers:

\[\begin{array}{ccccccccccccccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 0 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 8 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 1 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 9 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 2 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 10 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 3 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 11 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 4 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 12 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 5 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 13 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 6 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \rightarrow 14 \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 7 & & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \rightarrow 15 \\ \end{array}\]Positive whole numbers

Here is another way of looking at it:

\[\begin{array}{ccccc} \fcolorbox{black}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ \fcolorbox{black}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \times 2^3 & \fcolorbox{black}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \times 2^2 & \fcolorbox{black}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \times 2^1 & \fcolorbox{black}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \times 2^0 \\ \end{array}\]Positive whole numbers

Suppose we have the following sequence of bits:

\[ \begin{array}{cccccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \\ % \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ % \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^3 & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^2 & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \times 2^1 & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^0 \\ % \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ % 8 & 4 & 0 & 1 \\ % \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ % 8 & +\quad4 & +\quad0 & +\quad1 & = & 13 \end{array} \]

Positive whole numbers

We assign weights to each bit according to their position:

\[ \begin{array}{cccccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^3 & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^2 & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \times 2^1 & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^0 \\ % \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ % 8 & 4 & 0 & 1 \\ % \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ % 8 & +\quad4 & +\quad0 & +\quad1 & = & 13 \end{array} \]

Positive whole numbers

We assign weights to each bit according to their position:

\[ \begin{array}{cccccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^3 & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^2 & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \times 2^1 & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^0 \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ 8 & 4 & 0 & 1 \\ % \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ % 8 & +\quad4 & +\quad0 & +\quad1 & = & 13 \end{array} \]

Positive whole numbers

And this is why this sequence of bits represents the number 13:

\[ \begin{array}{cccccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^3 & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^2 & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \times 2^1 & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times 2^0 \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ 8 & 4 & 0 & 1 \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ 8 & +\quad4 & +\quad0 & +\quad1 & = & 13 \end{array} \]

But we need negative numbers too!

In practice, we reserve the first bit to represent the sign of the number:

\[ \begin{array}{c|ccccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ \textcolor{green}{+} & 4 & 0 & 1 \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ \textcolor{green}{+} & 4 & +\quad0 & +\quad1 & = & +5 \\ \textcolor{green}{sign} & \text{value} & & & & \\ \end{array} \]

But what if we need negative numbers?

In this case, we reserve the first bit to represent the sign of the number:

\[ \begin{array}{c|ccccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ \textcolor{red}{-} & 4 & 0 & 1 \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow \\ \textcolor{red}{-} & 4 & +\quad0 & +\quad1 & = & -5 \\ \textcolor{red}{sign} & \text{value} & & & & \\ \end{array} \]

Integers in Python

In Python, whole numbers are represented using the int data type:

Or simply:

⏳ 3-Minute Exercise: Binary to Decimal

Challenge: Calculate the equivalent decimal number that is represented by the following 8-bit signed integer. You can use a calculator to assist you.

\[ \begin{array}{c|cccccccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \end{array} \]

What is the correct answer?

Option 1️⃣ : + 181

Option 2️⃣ : - 53 👈

Option 3️⃣ : + 53

Don’t Worry!

💡 You won’t need to do this type of calculation manually in this course!

However, understanding the theory behind binary numbers and how data is stored is crucial for:

- Using libraries like

numpyandpandas:- Choosing the correct data types (e.g.,

int32,float64) for efficient memory usage. - Avoiding common pitfalls like overflow errors.

- Choosing the correct data types (e.g.,

- Working with real-world datasets:

- Interpreting binary and encoded data formats.

- Debugging issues with unexpected data values.

Enjoy the simplicity of Python for now, but remember: what’s under the hood matters!

What If I need a decimal number?

Decimal numbers are represented using the floating-point data type.

\[ \textcolor{#9753b8}{\texttt{pi}} = 3.14159 \]

In Python:

If you use a decimal point in a number, Python will automatically use the float data type.

How to represent floating-point numbers?

It gets more complicated…

We usually have a \(\textcolor{red}{sign}\) bit, an \(\textcolor{green}{exponent}\), and a \(\textcolor{blue}{mantissa}\). For example, if I only had 8 bits at my disposal (not a good idea), I could represent decimal numbers like this:

\[ \begin{array}{c|ccc|cccccc} \fcolorbox{red}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} & \fcolorbox{green}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} & \fcolorbox{green}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} & \fcolorbox{green}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} & \fcolorbox{blue}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} & \fcolorbox{blue}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} & \fcolorbox{blue}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} & \fcolorbox{blue}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow\\ \textcolor{red}{sign} & \textcolor{green}{\text{exp. sign}} & \fcolorbox{green}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \times 2^1 & \fcolorbox{green}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \times 2^0 & \fcolorbox{blue}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \times 2^{-1} & \fcolorbox{blue}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \times 2^{-2} & \fcolorbox{blue}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \times 2^{-3} & \fcolorbox{blue}{white}{$\phantom{0}$} \times 2^{-4} \\ \end{array} \]

The value of decimal number is retrieved using the formula:

\[ \textcolor{red}{\text{sign}} \times 10^{\textcolor{green}{\text{exp. sign}}\times(\textcolor{green}{\text{exponent number}})} \times \textcolor{blue}{\text{mantissa}} \]

How to represent floating-point numbers?

For example:

\[ \begin{array}{c|ccc|cccccc} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow\\ \textcolor{red}{-} & \textcolor{green}{-} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times \textcolor{green}{2^1} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \textcolor{green}{\times 2^0} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times \textcolor{blue}{2^{-1}} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times \textcolor{blue}{2^{-2}} & \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \times \textcolor{blue}{2^{-3}} & \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \times \textcolor{blue}{2^{-4}} \\ \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow & \downarrow\\ \textcolor{red}{-} & \textcolor{green}{-} & \textcolor{green}{2} & \textcolor{green}{0} & \textcolor{blue}{0.5} & \textcolor{blue}{0.25} & \textcolor{blue}{0.125} & \textcolor{blue}{0} \\ \end{array} \]

Now we do some calculations:

\[ \begin{array}{c|ll} \textcolor{red}{sign} & \textcolor{red}{-} & \text{(negative number)} \\ \textcolor{green}{exponent} & 10^{\textcolor{green}{-(2+0)}} = \textcolor{green}{\textbf{0.01}} & \text{(assume base 10)} \\ \textcolor{blue}{mantissa} & \textcolor{blue}{0.5} + \textcolor{blue}{0.25} + \textcolor{blue}{0.125} = \textcolor{blue}{\textbf{0.875}} & \\ \hline \textbf{Result} & \textcolor{red}{-} \quad \textcolor{green}{\textbf{0.01}} \times \textcolor{blue}{\textbf{0.875}} = -0.00875 \\ \end{array} \]

How to represent floating-point numbers?

When we start using numpy and pandas, we will have to consider the number of bits used to represent floating-point numbers. The most typical sizes are:

float16(half precision): 16 bitsfloat32(single precision): 32 bitsfloat64(double precision): 64 bits

See all numpy floating data types here.

What about text?

The ASCII table

In the early days of computing, text was represented using the ASCII table. ASCII uses 7 bits to represent each individual character.

Here are some examples:

The letter ‘A’ is represented by the number 65 encoded in binary as:

\[ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \]

The letter ‘a’ (lowercase) is represented by the number 97 encoded in binary as:

\[ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \]

The linebreak character ‘\n’ is represented by the number 10 encoded in binary as:

\[ \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#111111}{$\textcolor{white}{1}$} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \fcolorbox{black}{#eeeeee}{0} \]

UTF-8

The ASCII table is very limited. It can only represent 128 characters. UTF-8 is a more modern text representation that was built to be compatible but can represent over 1 million characters.

🤗 Emojis are part of UTF-8!

The number of bits used to represent a character in UTF-8 can vary from 8 to 32 bits. The most common characters, like the English alphabet, are still represented using just 8 bits. (Read more)

What do we mean by data science?

We will come back to thinking about data types very frequently in this course. But let me zoom out for a moment and prepare you for what’s coming next.

Data science is…

“[…] a field of study and practice that involves the collection, storage, and processing of data in order to derive important 💡 insights into a problem or a phenomenon.

Such data may be generated by humans (surveys, logs, etc.) or machines (weather data, road vision, etc.),

and could be in different formats (text, audio, video, augmented or virtual reality, etc.).”

The Data Science Workflow

⚠️ Note that this is a simplified version of what happens in a data science project.

In practice, the process is not linear, and many feedback loops exist.

The Data Science Workflow

It is often said that 80% of the time and effort spent on a data science project goes to the abovementioned tasks.

The Data Science Workflow

And this is what this course is about! You will learn some of the most common tools used during this process.

In Practice… 👨🏻💻

Let me show you how precisely we will work with Python and data in this course.

LIVE DEMO

▶ VS Code

▶ Jupyter Notebooks

▶ Python Kernel

What happens in the 💻 W01 Lab

Practise using Python in a Jupyter Notebook environment.

Put your Python skills to the test.

The lab assumes you’ve done the Dataquest lessons listed on the 📝 Week 01 Practice.

Practice integers, floats, and strings.

But also, lists! (more on lists in the next lecture)

Extensive practice with the

print()function

🚀 PRO TIP: Try to work on the take-home exercise afterwards. It will help you get the necessary practice for the 📝 Week 02 Practice (Formative).

Any Burning Questions? 🔥

References

![]()

LSE DS105W (2024/25)