🗓️ Week 08

Machine Learning II

DS101 – Fundamentals of Data Science

17 Nov 2025

Completing Our Supervised Learning Toolkit

⏪ Quick Recap: Where We Left Off

Last week (W07) we covered:

- ✅ Machine Learning basics: What ML is, how it learns

- ✅ Supervised Learning: Using labelled data

- ✅ Logistic Regression: Predicting Hit/Flop songs

- ✅ Decision Trees: Rule-based learning

- ✅ Model Evaluation: Precision, recall, F1, confusion matrices

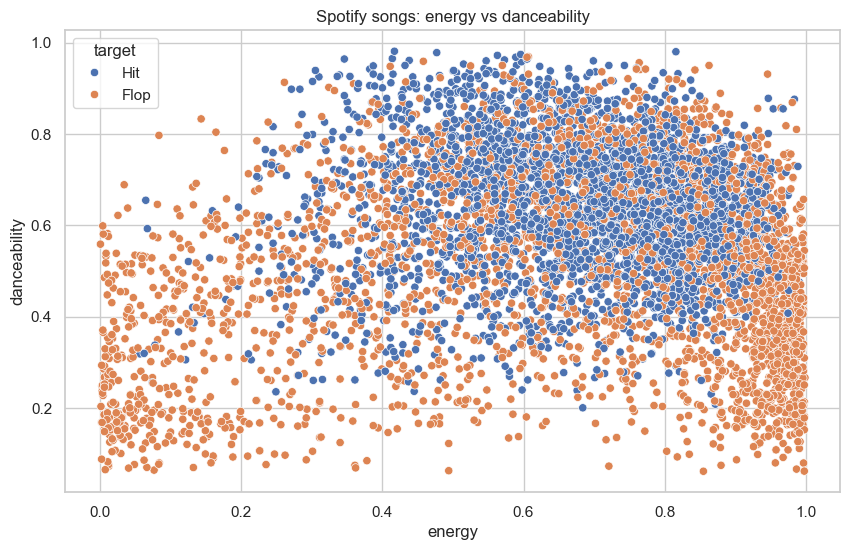

Our Spotify example:

- 40,000+ songs (1960–2019) (we focused on songs from 2010 to 2019)

- Features: danceability, energy, valence, tempo

- Target: Hit or Flop (Billboard Hot-100)

- High energy/danceability → higher hit likelihood

- Acoustic/instrumental → more likely flops

Today: Finish supervised learning → pivot to unsupervised!

Today’s Roadmap

Part 1: Supervised (~40–45 min)

- Support Vector Machines

- Maximum margin

- The kernel trick

- Neural Networks

- Neurons & layers

- Function composition

- Deep Learning

- Why many layers?

- Attention & Transformers

- The context problem

- What attention solves

- Why transformers matter

Part 2: Unsupervised (~60–70 min)

- The Paradigm Shift

- No labels, new goals

- Four Families

- Clustering

- Association rules

- Dimensionality reduction

- Anomaly detection

- Math of Similarity

- Distance & similarity metrics

- Live Demo

- K-means

- DBSCAN

Moving beyond trees and logistic regression

So far, we have seen:

- Logistic regression → draws one straight decision boundary

- Decision trees → draw step-shaped, axis-aligned regions

- Ensembles of trees → combine many such regions

These make different assumptions about how classes are separated in feature space.

Now we introduce a classifier that takes a geometric view: it explicitly asks which boundary is safest.

Why introduce another classifier?

Logistic regression draws one straight line. Decision trees draw blocky, step-like regions. Both are useful, but:

- many reasonable boundaries can fit the same data

- trees’ rectangular splits can be unstable and hard to visualise

- logistic regression is limited to straight boundaries

- real data often overlap and have messy shapes

Support Vector Machines approach the problem differently: they look for the most robust boundary using geometry.

Different models draw different boundaries

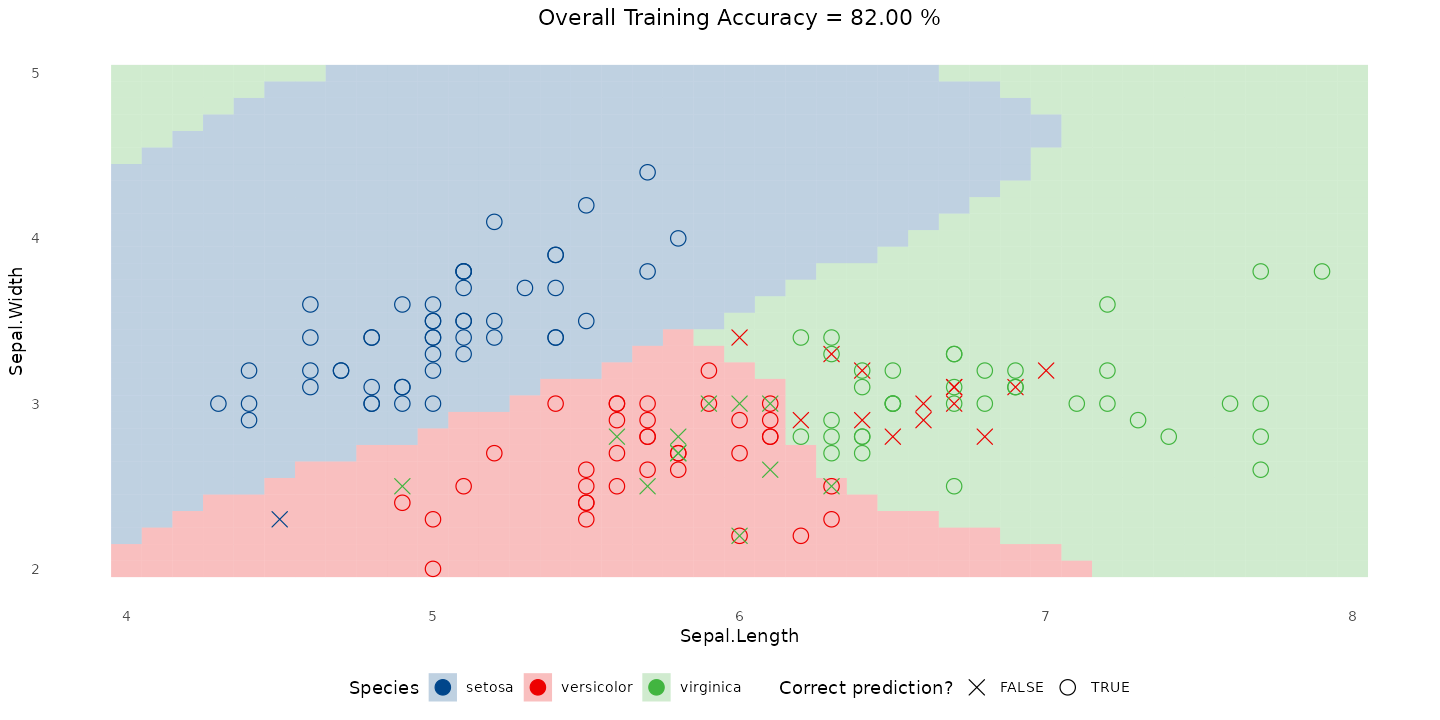

To motivate why SVMs matter, let’s compare how three familiar classifiers behave on the exact same data (Setosa vs Virginica from the Iris dataset):

Logistic regression

Draws one straight line as the decision boundary

Models the log-odds of the positive class:

\[ \log\left(\frac{p(\text{class}=1)}{p(\text{class}=0)}\right) \] as a linear function of the features

Interpretable, but limited to straight boundaries

Decision tree

- Splits the space using axis-aligned cuts

- Produces step-shaped, rectangular regions

- Flexible but can create unstable, jagged boundaries

Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- Also produces a straight boundary for this dataset

- But chooses it using a margin-maximisation principle

- Often generalises better than a line chosen only by fitting probabilities

Next slide: all three models on identical features.

Different models draw different boundaries

Many possible separating lines

If the two classes can be separated, there isn’t just one solution: there are infinitely many valid separating lines.

SVM asks:

Among all separating lines that classify the training data correctly, which one is the safest?

The maximum-margin idea

SVM chooses the line that maximises the margin — the safest separation between classes.

- Margin = the distance between the decision boundary and the nearest training points from each class

- These nearest points (one or more per class) are the support vectors

- These critical points alone determine the SVM boundary

- The SVM chooses the line that keeps these points as far away as possible

- A wider margin usually leads to better generalisation

Soft-margin SVMs

Soft margins: real data is messy

Perfect separation is rare:

- Spotify hits vs flops

Soft margins: real data is messy

- Benign vs malignant tumours

- Many social-science datasets

Soft margins: real data is messy

Classes naturally overlap. Forcing a perfectly separating boundary often:

- overfits noise

- produces unstable boundaries

- badly misclassifies future data

Soft-margin SVM relaxes the “no errors” rule:

- allows points to lie inside the margin

- even permits some misclassifications

- still aims to keep the margin as wide as possible overall

The key tuning knob is the parameter C.

The role of C

In the SVM optimisation, C is a positive parameter controlling how strongly we penalise violations of the margin.

Interpretation:

Large C

- strong penalty for misclassification

- model insists on classifying almost every training point correctly

- margin becomes narrow

- risk: overfitting

Small C

- weak penalty for violations

- model accepts some errors to maintain a wide, stable margin

- often better generalisation on noisy/overlapping data

C is the model’s strictness.

Soft-margin SVM on Spotify hits/flops

Hit vs flop songs using energy and danceability:

- The two classes overlap heavily

- No straight line can separate them well

- Soft-margin SVM finds a compromise boundary balancing width vs classification errors

This plot also shows why linear SVM is a poor choice for this dataset.

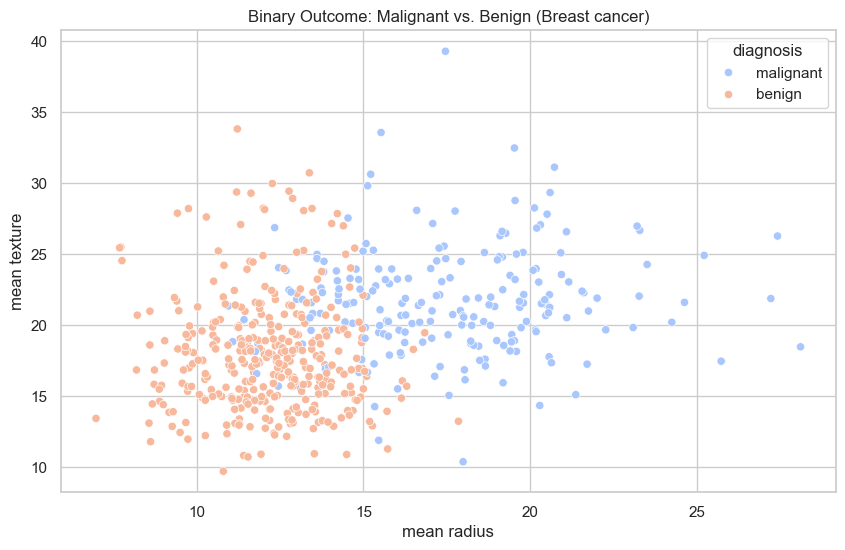

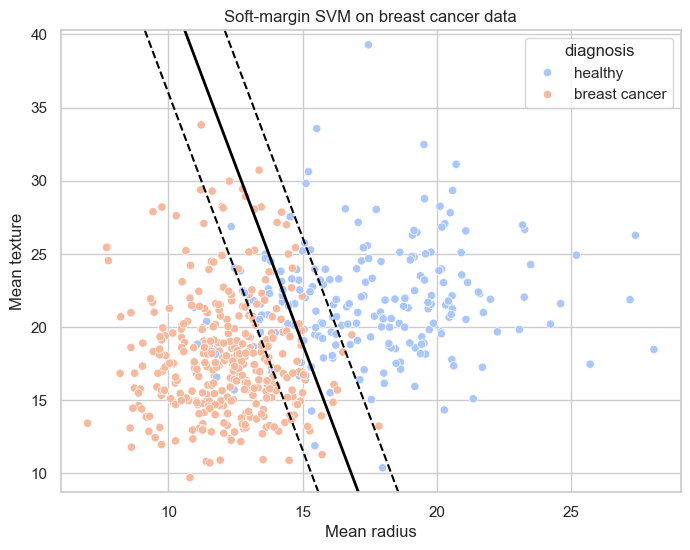

Soft-margin SVM on breast cancer data

Benign vs malignant tumours (2D projection):

- Noticeable overlap between classes

- Soft-margin SVM avoids forcing any brittle perfect separator

- The balance between errors vs margin width is visible in the geometry

Non-linear SVMs

When straight lines are not enough

Sometimes even with soft margins:

- no straight line works

- tree boundaries look too jagged

- classes form curved shapes

We need a classifier that can draw smooth curved boundaries while still using the maximum-margin idea.

This is where kernels enter.

The kernel trick

Idea:

- Imagine mapping the data into a higher-dimensional space

- In that space, a straight line may separate the classes

- Find that line (a maximum-margin hyperplane)

- When projected back down, it becomes a curved boundary

SVMs do all this implicitly using a kernel function— we never compute the high-dimensional coordinates.

Common kernels:

- Linear → straight line

- Polynomial → polynomial curves

- RBF (Gaussian) → smooth flexible shapes (most common)

Kernel SVM on iris (three species)

RBF kernel finds smooth, curved regions separating all three iris species:

Non-linear SVM on Spotify songs

For Spotify hits/flops, a curved RBF boundary works far better than any straight line:

Summary: why SVMs matter

SVMs give us:

- a principled way to choose the safest separating line

- robustness to noise and overlap via soft margins

- ability to model complex shapes via kernels

- models determined only by critical points (support vectors)

They complete our supervised learning toolkit alongside logistic regression and decision trees.

SVM is especially useful when:

- you have medium-sized datasets

- you care about robust, well-separated boundaries

- patterns may be nonlinear but you don’t want to jump straight to deep learning

Where SVMs struggle

- Interpretability: Hard to explain — we can’t easily visualize “why.”

- Computation: Can be slower on very large datasets.

- Tuning: Need careful choice of kernel and parameters.

🎧 SVM on Spotify Songs

Performance Metrics:

Classification Report:

precision recall f1-score support

Flop 0.89 0.73 0.80 960

Hit 0.77 0.91 0.83 960

accuracy 0.82 1920

macro avg 0.83 0.82 0.82 1920

weighted avg 0.83 0.82 0.82 1920Confusion Matrix:

📊 Interpretation:

- Accuracy improved slightly to ~82 %.

- The SVM correctly classifies more hits than the tree or logistic regression.

- It handles curved, overlapping relationships better than straight-line or boxy splits.

- But SVMs are harder to interpret — we lose the clear “if–then” logic of trees.

💡 Conceptual takeaway: The model isn’t just smarter — it’s smoother. It balances flexibility and generalization without memorizing the data.

Model comparison

Neural Networks, Deep Learning, Attention & Transformers

Neural networks: from simple to expressive

So far, our models produced decision boundaries with fixed shapes:

- Logistic regression → a single straight line

- Decision trees → step-shaped, axis-aligned regions

- SVMs → the safest straight line (or curved if using kernels)

Neural networks take a more flexible approach:

They learn complex boundaries by composing many simple functions.

To see how, we start with a single neuron.

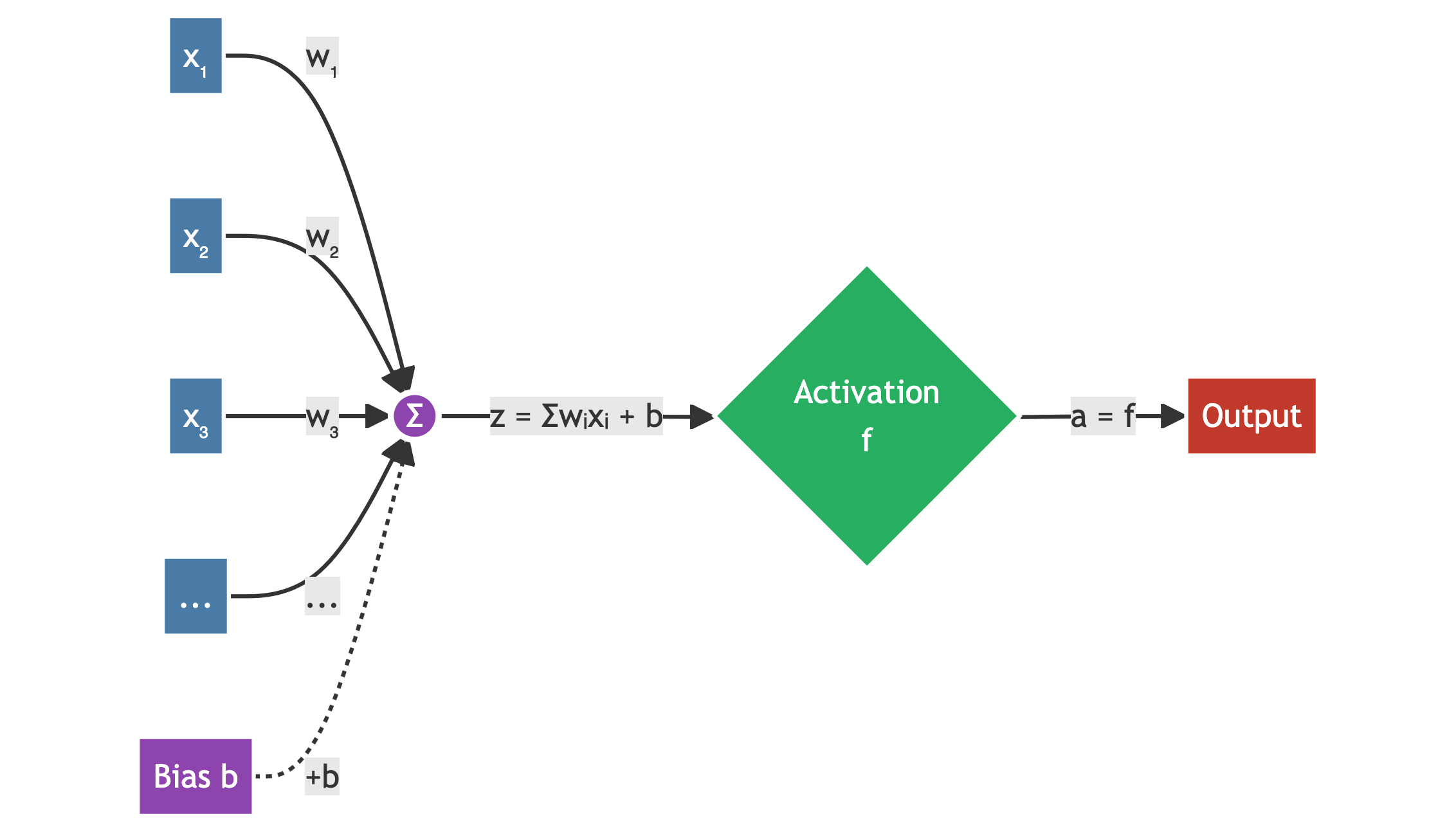

The neuron: weighted input → transformation

A neuron computes:

\[ z = w_1 x_1 + w_2 x_2 + \dots + w_n x_n + b \]

\[ \text{output} = f(z) \]

Where:

- \(w_i\): weights

- \(b\): bias

- \(f(\cdot)\): activation function (e.g., ReLU, sigmoid)

It’s a small, flexible function that can bend a decision boundary.

Diagram:

Stacking neurons: learning in layers

By linking neurons into layers, networks can learn richer patterns:

- Layer 1 → basic combinations of inputs

- Layer 2 → combinations of Layer 1 features

- Layer 3 → higher-level structure

Each layer transforms what the previous one learned.

Neural network vs deep learning

A neural network is any model built from neurons. This includes:

- models with no hidden layers (e.g., logistic regression)

- networks with one or two hidden layers

- larger multi-layer architectures

Deep learning refers to neural networks that have many layers stacked together.

The building blocks are the same, but depth allows the model to learn increasingly abstract and complex representations.

All deep learning models are neural networks, but not all neural networks are “deep”.

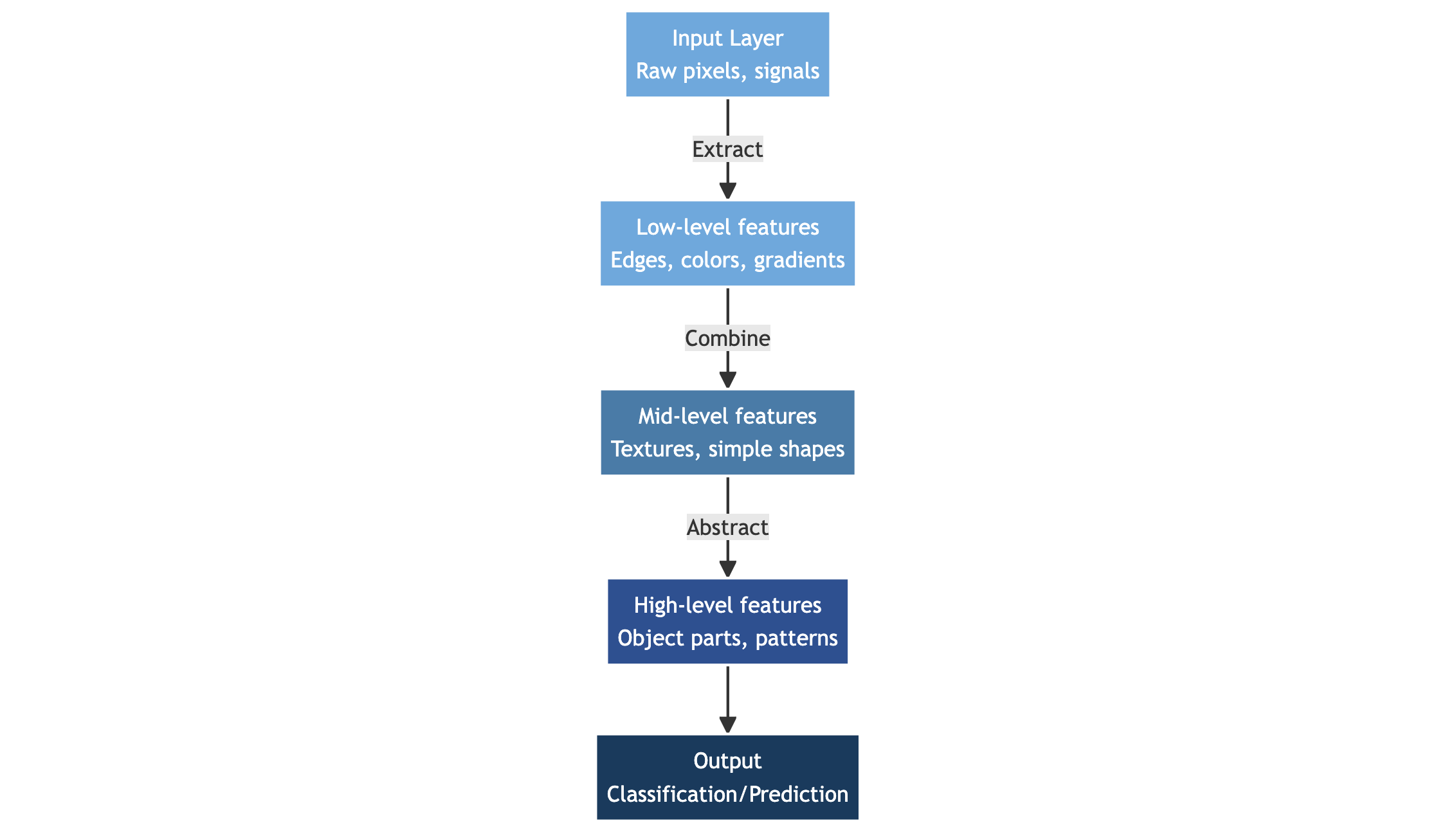

What is deep learning?

Deep learning uses networks with multiple successive layers. A deep network:

- Applies several weighted transformations in sequence

- Learns features at different levels of abstraction

- Can represent highly non-linear relationships

Formally:

\[ x \rightarrow f_1(x) \rightarrow f_2(f_1(x)) \rightarrow \dots \rightarrow f_L(\dots) \]

Diagram:

Why deep learning works

Deep networks build hierarchical representations:

Audio:

- Lower layers: simple frequency patterns

- Mid layers: rhythm / timbre

- Higher layers: genre or mood

Images:

- Edges → shapes → objects

Tabular data:

- Interactions between features

- Automatically learned combinations

- Flexible, non-linear boundaries

Depth = expressive power.

But deep networks process sequences poorly on their own, which leads to…

Attention & Transformers

Before transformers: what RNNs tried to do

Earlier sequence models used Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs).

They worked like this:

- Read the input one word at a time

- Kept a small memory of what came before

- Used that memory to interpret the next word

Conceptually:

word1 → memory → word2 → memory → word3 → memory → ...Limitations:

- The memory is small → easily forgets earlier words

- Hard to connect distant parts of a sentence

- Processing is sequential → slow to train

Transformers were created to overcome these limits.

The context problem

Sequential models struggle with long-distance dependencies.

Example (linguistic):

“The animal didn’t cross the street because it was too tired.”

“it” refers to animal, not street.

Example (social science):

“The central bank raised rates, but economists expect them to fall next year.”

“them” refers to rates, not economists.

Models that only remember a small recent context often fail here.

Attention: learning what to focus on

Attention solves the context problem by letting each word:

Look directly at any other word and decide how important it is.

It assigns attention weights that highlight relevant parts of the input.

This enables:

- Long-range understanding

- Better handling of references and ambiguity

- Efficient learning on long sequences

Diagram:

Multi-head attention

A single attention pattern is often not enough.

Multi-head attention uses several attention mechanisms in parallel:

- One head may track syntax

- Another captures semantic similarity

- Another identifies long-distance links

- Another focuses on local patterns

Each head provides a different perspective on the input.

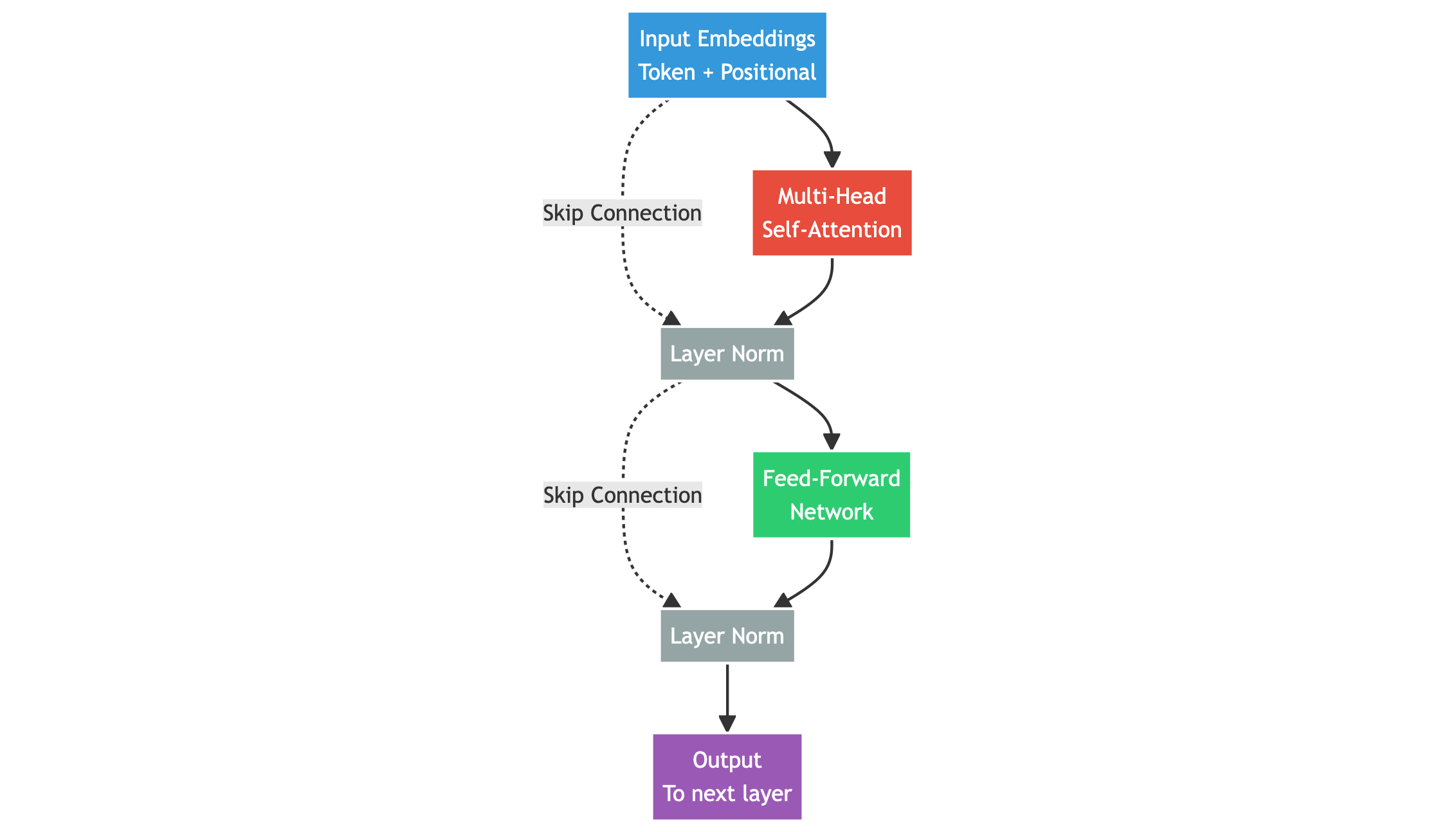

Transformers: architecture built around attention

Transformers remove recurrence and rely entirely on attention:

- Inputs receive positional encodings (to reflect word order)

- Each word can use information from any other word

- Layers of multi-head attention + feed-forward networks refine meaning

- Fully parallel operations → fast training

- Highly scalable → extremely deep and large models

Transformers now power:

- GPT-style language models

- Machine translation

- Image generation (e.g., DALL·E)

- Speech and audio processing

- Protein folding (AlphaFold)

- Most modern AI systems

Canonical architecture diagram:

What you should remember

- Neural networks learn functions by combining simple building blocks

- Deep networks use many layers to learn hierarchical representations

- Attention lets models focus on the most relevant information

- Transformers scale attention and dominate modern AI

The pivot: from supervised to unsupervised learning

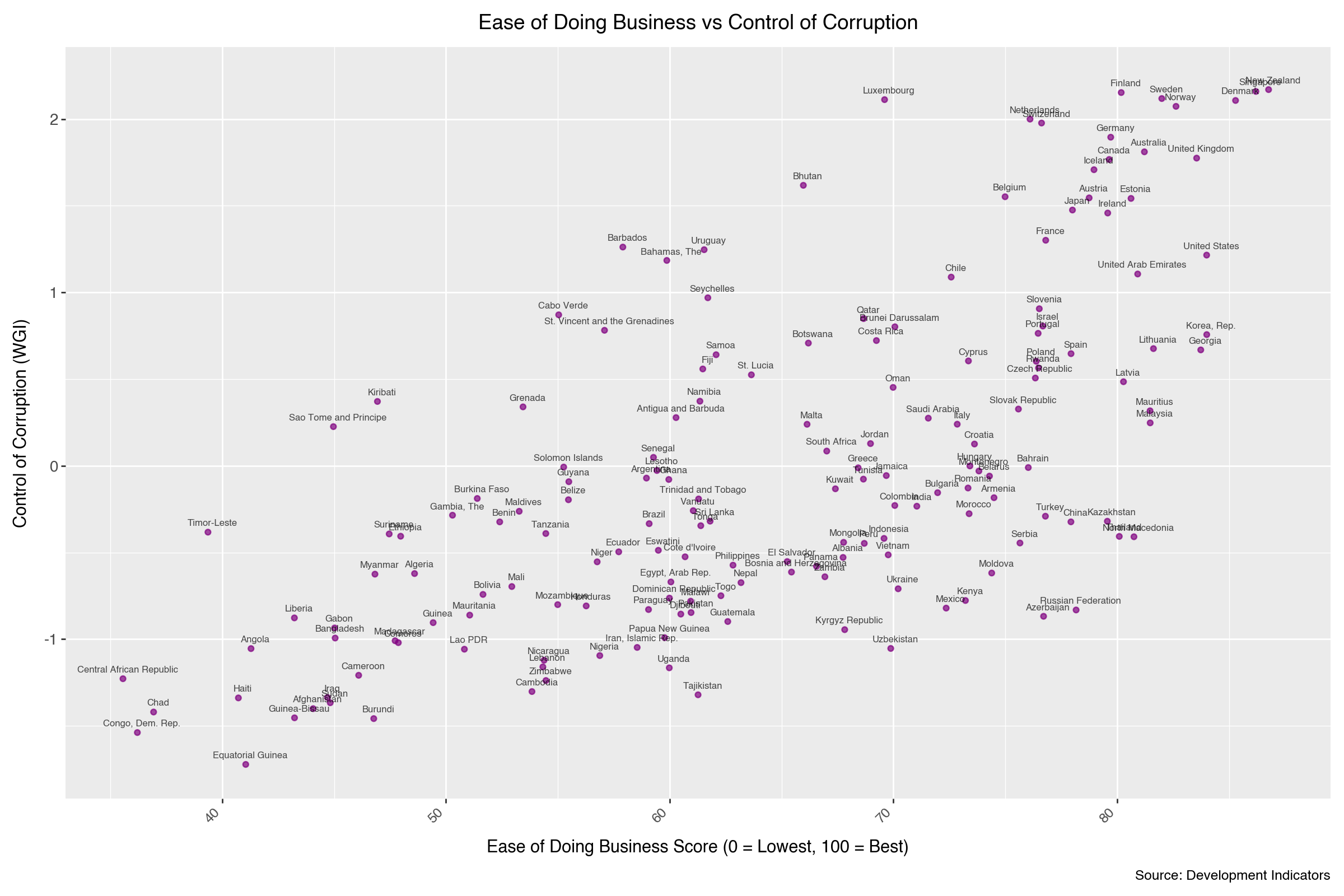

A challenge without labels

Imagine you’re a sociologist studying global development.

You have data on ~170 countries:

- GDP per capita

- Life expectancy

- Education outcomes

- Governance quality

- Corruption control

- Infrastructure indicators

But no one tells you which countries are:

- “developed”

- “developing”

- “emerging”

- “high-growth”

- “fragile”

You just get a big table of numbers — no labels.

A first look at the data

Even without labels, you might notice:

- some countries that sit close together

- others that are clearly far apart

- a kind of band or gradient

- a few isolated points that don’t fit the main pattern

At this stage, these are just visual impressions, not conclusions.

We will analyse this dataset properly later in a live clustering demo.

Why unsupervised approaches matter

Real-world labels are often:

- Expensive

- Doctors labelling medical images

- Lawyers annotating legal cases

- Analysts manually tagging documents

- Doctors labelling medical images

- Slow

- Coding thousands of survey responses

- Classifying millions of transactions

- Coding thousands of survey responses

- Ambiguous

- What counts as “developed”?

- Who exactly is a “swing voter”?

- What counts as “developed”?

- Constantly changing

- Cybersecurity threats evolve every week

- Fraudsters adapt to existing detection rules

- Cybersecurity threats evolve every week

- Too many or unknown

- Thousands of distinct malware families

- Rare events that have never occurred before

- Thousands of distinct malware families

In many domains, we cannot rely on labels.

We still want to learn structure → this is where unsupervised learning comes in.

You’ve been doing this all along

Your own brain does unsupervised learning constantly:

- At a party → you notice groups of people who belong together

- In the news → you mentally group stories by topic

- In music → you recognise genres without seeing labels

- When shopping → you see types of customers or products

What you naturally do:

- spot patterns

- group similar things

- notice outliers

- impose structure on raw experience

Unsupervised algorithms aim to do the same, but:

- on larger scales

- with more consistency

- and in higher dimensions

Two paradigms of machine learning

Supervised learning

We learn from examples with answers.

(X, Y) pairs → learn mapping X → Y- Inputs X (features)

- Outputs Y (labels)

- Goal: predict Y for new X

Examples:

- Song features → Hit or Flop

- Patient data → Disease / No disease

- Email text → Spam / Not spam

Unsupervised learning

We only have X (no labels).

X → discover structure / patterns- Inputs X (features)

- No Y

- Goal: discover how data are organised

Examples:

- Find groups of similar countries

- Detect unusual transactions

- Discover voter “types”

- Identify topics in news articles

Four families of unsupervised learning

Overview

We will focus on four broad families:

Clustering

- Group similar items together

Association rule mining

- Find patterns of co-occurrence (“if X, then often Y”)

Dimensionality reduction

- Turn many features into a smaller number of meaningful dimensions

Anomaly detection

- Flag items that are very different from the rest

Before any equations, we will build intuition with real-world examples.

Clustering

Clustering: discovering natural groups

Definition:

Divide data into groups (clusters) such that:

- points in the same cluster are relatively similar

- points in different clusters are relatively dissimilar

No labels are given — clusters are discovered, not predefined.

To get an idea of the breadth of existing clustering algorithms, see the scikit-learn documentation

Clustering in political science: voter segmentation

Traditional categories like “Labour vs Conservative” can miss important nuances.

Researchers1 cluster voters based on:

- values and identities

- trust in institutions

- views on immigration, inequality, climate

- social and cultural attitudes

A major UK study by More in Common (2022–2025) identifies seven “segments” such as:

- Progressive Activists

- Disengaged Battlers

- Loyal Nationals

- Established Liberals

- Traditional Conservatives

These segments:

- cut across party lines

- explain why voters sometimes switch parties

- help understand polarisation and realignment

Clustering in international relations: hidden coalitions

Countries signal alliances publicly, but their UN voting records tell another story.

Cluster countries based on:

- how they vote on human rights

- development resolutions

- security issues

- climate agreements

We often find:

- blocks of countries that vote together

- “swing” states that shift between blocks

- alliances that do not match official treaties

Clustering reveals the latent structure of international politics.

Clustering in the Law and courts: case law patterns

Instead of reading thousands of judgments one by one, we can:

represent cases by:

- legal issues

- cited precedents

- outcome (plaintiff/defendant)

- language used

cluster cases to find:

- typical case families

- groups of judges with similar decision patterns

- areas of law that are inconsistent or rapidly evolving

This helps legal scholars and practitioners see the big picture.

Clustering in medicine: patient stratification

In many diseases, not all patients are alike.

Cluster patients using:

- clinical features

- lab results

- imaging

- sometimes genetics or gene expression

You may discover:

- subgroups that respond differently to treatment

- subtypes with very different prognoses

- forms of disease that were not recognised before

Classic example: breast cancer subtypes (e.g., HER2+, ER+, triple-negative), originally discovered using unsupervised methods on molecular data.

Association rule mining

Association rule mining: co-occurrence patterns

Goal: find rules of the form:

If X is present, Y is often also present

Not about causation — just discovering regularities in large datasets.

Market basket analysis: the classic example of association rule mining

Retailers have huge logs of transactions:

- each shopping basket is a set of items:

{bread, milk, eggs},{pasta, tomatoes, parmesan}, …

Association rule mining finds patterns (Agrawal, Imieliński, and Swami 1993) (Brin, Motwani, and Silverstein 1997) such as:

- “If bread is bought, butter is bought 60% of the time”

- “If pasta and tomato sauce are bought, parmesan is likely”

The famous (probably exaggerated, but useful to know about) story (see this page for the story):

Customers buying diapers often also bought beer.

Regardless of the exact details, the idea is:

co-occurrence reveals surprising links

which can be used for:

- store layout

- promotions

- recommendation systems

Association rule mining in public health: disease comorbidity

Electronic health records contain:

- diagnoses

- medications

- lab results

- demographic information

Association rule mining can uncover comorbidity patterns, e.g.:

- “Patients with type 2 diabetes often also have hypertension and later kidney disease.”

- “Patients with dementia often develop specific patterns of infections or frailty.”

- “Certain psychiatric diagnoses co-occur with sleep disorders and chronic pain.”

These patterns are useful for:

- screening programmes

- designing care pathways

- managing hospital resources

Examples: (El Khalifa, Yew, and Chi 2024) on dementia multimorbidity; (Bata et al. 2025) on diabetes-related comorbidities.

Dimensionality reduction

The problem: too many variables

Modern datasets often have many features:

- Countries: dozens of development, governance, inequality indicators

- Surveys: 40–80 questions

- Text: thousands of word frequencies

- Genomics: tens of thousands of genes

Problems:

- Hard to visualise

- Hard to reason about

- Many features are redundant

- Noise can overwhelm signal

We need a way to compress without destroying meaning.

Dimensionality reduction: the idea

Dimensionality reduction:

Turn many correlated variables into a smaller number of informative dimensions.

Goals:

- simplify visualisation (2D, 3D plots)

- remove redundancy

- highlight main patterns

- help clustering and further analysis

This is not specific to machine learning — it appears in many fields.

The Human Development Index (HDI)

HDI is a classic example of dimensionality reduction in practice.

We have many development-related indicators:

- health outcomes

- education levels

- income

- and more

HDI focuses on three core components:

- Health → life expectancy

- Education → years of schooling

- Standard of living → GNI per capita (PPP)

Each component summarises several detailed indicators.

These are:

- normalised

- combined

- turned into a single score between 0 and 1

One number summarises a country’s overall development level.

HDI is not a machine-learning method, but it serves the same purpose as dimensionality reduction:

- many variables → one interpretable dimension

- easier ranking, mapping, and comparison

Why HDI is a dimensionality reduction example

HDI illustrates what dimensionality reduction does:

- combines a complex set of indicators

- reduces redundancy (many measures of “development” → one)

- makes broad patterns visible

- enables simple visualisations and comparisons

Machine learning methods generalise this idea:

- for more features

- in more complex datasets

- sometimes in non-linear ways

But the conceptual goal is the same:

Compress complexity into a smaller number of meaningful dimensions.

A brief tour of dimensionality reduction methods

You don’t need the details in DS101, just the intuition:

PCA (Principal Component Analysis)

- Finds the directions along which the data vary the most

- In country data: could reveal a “development” axis and a “governance” axis

Factor analysis

- Groups variables that tend to move together

- Example: several governance indicators forming an “institution quality” factor

MCA (Multiple Correspondence Analysis)

- Like PCA, but for categorical/ordinal variables (e.g. survey responses)

Autoencoders (deep learning)

- Neural nets that learn a compressed representation by forcing data through a small “bottleneck”

- Useful for large, complex, non-linear datasets

The key takeaway:

Many variables → a few dimensions → structure becomes easier to see.

Anomaly detection

The goal: find unusual cases

Sometimes the most important observations are the rare, strange, or unusual ones.

Anomaly detection:

Identify data points that do not fit with the majority.

Applications:

- fraud detection

- cyber-security

- journalism and investigations

- fault detection in engineering

- medical diagnosis

Cyber-security: intrusion detection

Normal patterns:

- logins from usual locations

- typical working hours

- standard data transfer volumes

Anomalies:

- login from a country never seen before

- access at 3 a.m. from a senior official’s account

- large, unexpected data downloads

- weird sequences of commands

These anomalies:

- may be false alarms

- but may also indicate attacks or compromised accounts

Labels are hard here:

- new attacks appear all the time

- old labels may not describe new threats

- unsupervised or semi-supervised methods are crucial

For literature on the topic, see (Goswami 2024), (Han et al. 2020), (Berrada et al. 2020) and (Benabderrahmane et al. 2021)

Finance: fraud detection

Normal behaviour:

- regular small purchases

- typical shops and locations

- consistent spending patterns

Anomalies:

- sudden very large purchases

- repeated transactions just below a threshold

- purchases in two distant cities within an impossible time window

These stand out as:

- far from the customer’s “normal” profile

- rare relative to the bulk of transactions

Anomaly detection can flag these for investigation.

Journalism: the Panama Papers

The Panama Papers (2016):

- 11.5 million leaked documents

- ~2.6 terabytes of data

- 214,000 offshore entities

Impossible for journalists to read everything.

So they used data analysis tools:

graph databases (e.g. Neo4j) to model companies, people, accounts

visual network exploration tools (Linkurious)

text mining to extract names, relationships, jurisdictions

algorithms to highlight unusual patterns:

- complex ownership chains

- unusual paths through multiple tax havens

- shell companies with no clear economic activity

Many big stories began with anomalous patterns:

- a politician’s name appearing in unexpected contexts

- money flowing through strange routes

- rare structures in the network of companies

In many ways, the anomalies were the story.

For more on the story, see this page

The unifying idea: similarity and distance

Same theme, different problems

We’ve seen four different families:

- clustering

- association rule mining

- dimensionality reduction

- anomaly detection

They look quite different, but deep down they share a common idea:

We are always asking: what is similar to what, and what is different?

How similarity appears in each family

Clustering

- Items that are close together (in feature space) → same cluster

- Items that are far apart → different clusters

Dimensionality reduction

- Try to keep near things near and far things far in a lower-dimensional representation

Anomaly detection

- Anomalies are items that are far away from most others

- Or lie in regions of very low density

Association rules

- Items or events that co-occur frequently behave in a similar way in transaction space

- Overlap between sets (e.g. baskets, diagnoses) is a kind of similarity

Why this matters

This common theme guides everything that comes next:

- We need to decide mathematically what “similar” means

- Different choices → different structures and clusters

- Our distance metric effectively defines our notion of similarity

Next:

- We’ll look at distance and similarity metrics

- Then see how they drive clustering algorithms like K-means and DBSCAN

- And apply them to our country development dataset

The mathematics of similarity

Why distance matters

To use unsupervised methods, we often represent each data point as a vector of features.

We then measure:

How far apart are two vectors? How similar are they?

This requires a distance or similarity function.

Distance metrics: continuous data

Euclidean distance

The most familiar one:

\[ d(A,B) = \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n (A_i - B_i)^2} \]

- straight-line (“as the crow flies”) distance

- sensitive to large differences in any coordinate

Use when:

- features are continuous

- on similar scales (after normalisation if needed)

- you care about overall geometric distance

Examples:

- country indicators (GDP, life expectancy)

- song features (energy, tempo)

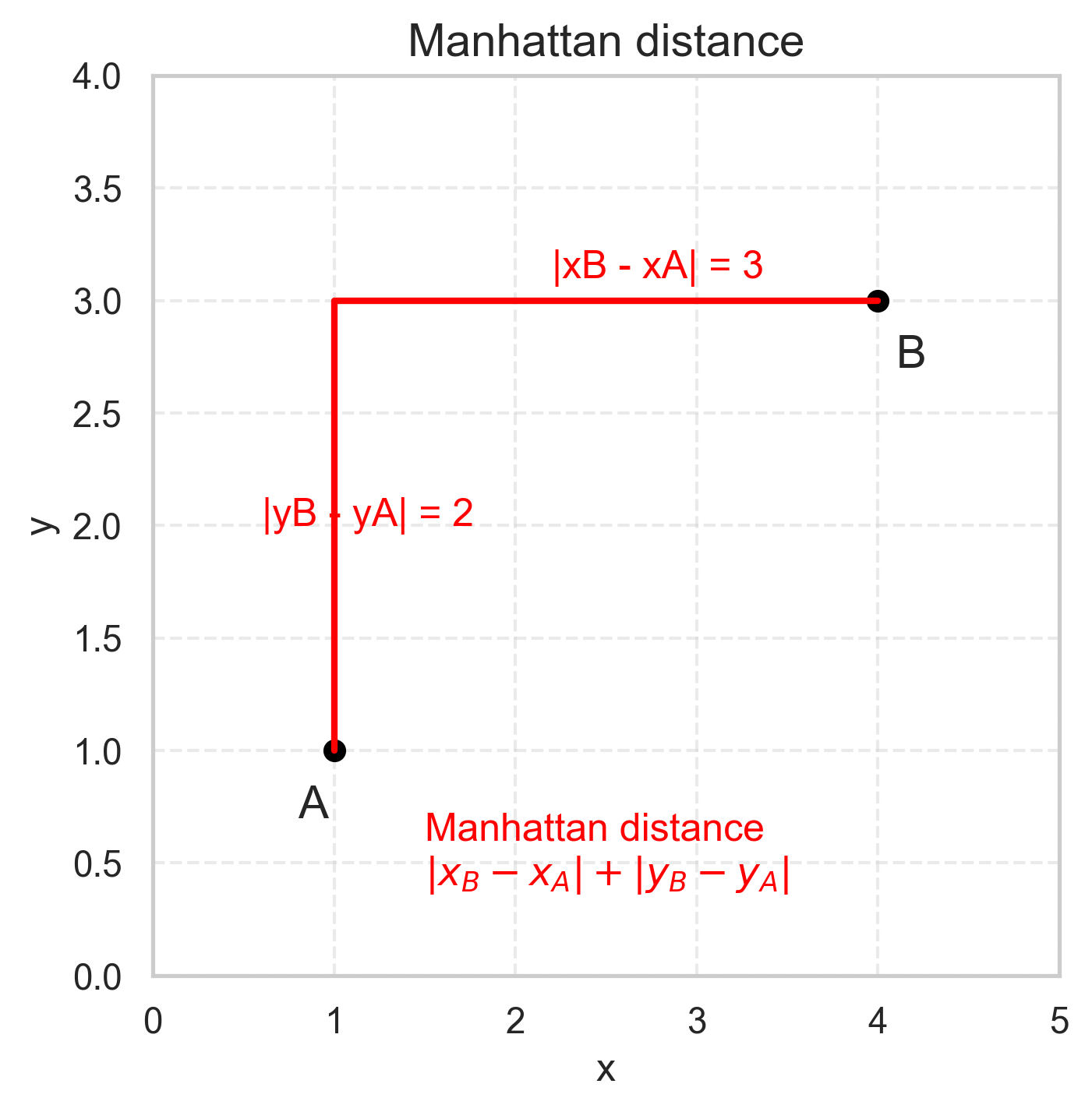

Manhattan distance

Also called L1 distance:

\[ d(A,B) = \sum_{i=1}^n |A_i - B_i| \]

- like walking in a grid (“city block” distance)

- less sensitive to single big differences

Use when:

- you care about additive differences

- robustness to outliers is important

- features change in discrete steps

Example:

- survey responses encoded as 1–5 (Likert-type), after appropriate preprocessing

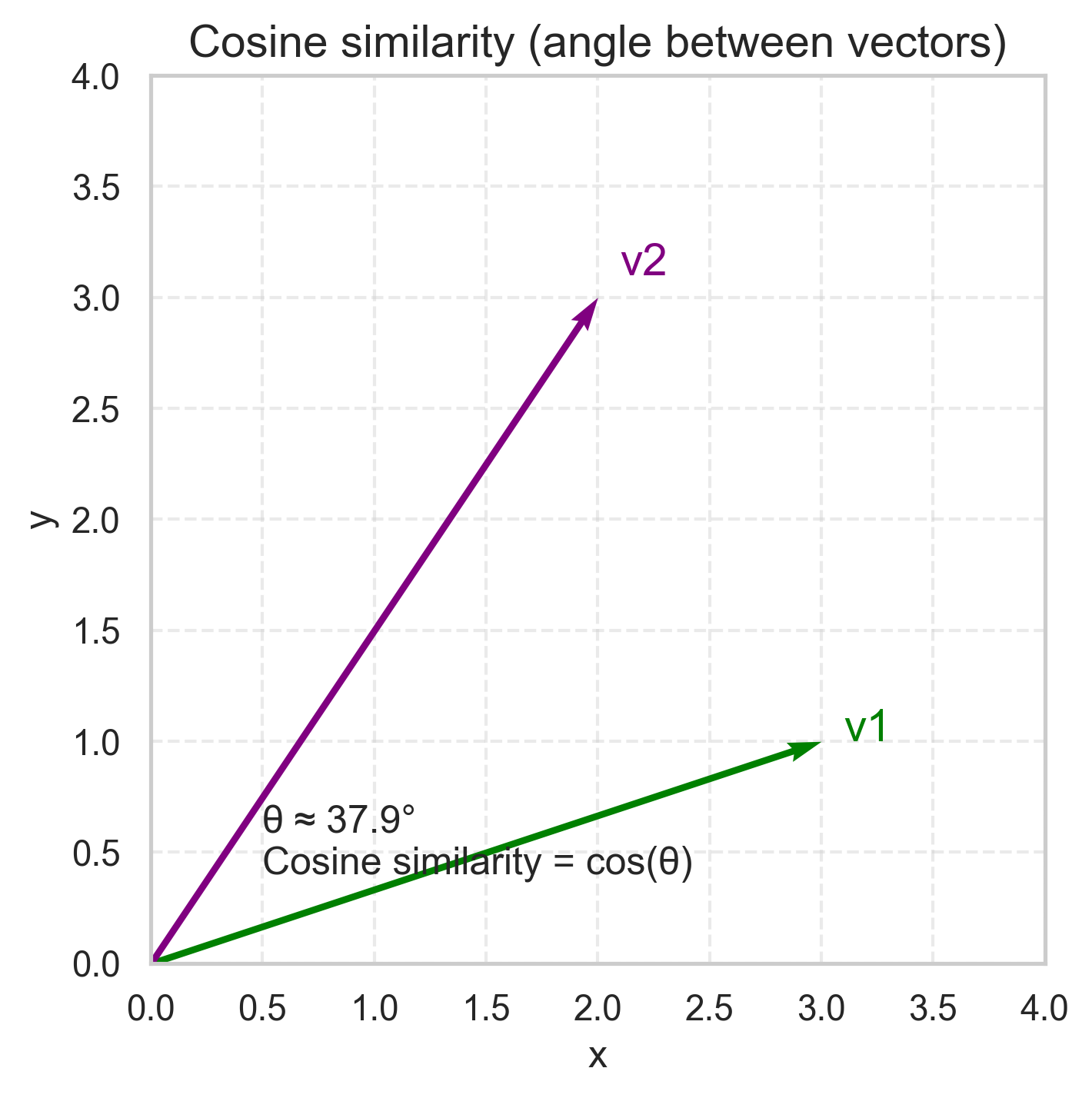

Cosine similarity

Instead of distance, a similarity:

\[ S_C(A,B) = \frac{\sum_i A_i B_i} {\sqrt{\sum_i A_i^2} \sqrt{\sum_i B_i^2}} \]

- measures the angle between two vectors

- ignores overall magnitude (length)

Useful when:

- direction matters more than scale

- you care about proportions, not absolute values

Examples:

- text (word-frequency vectors)

- budget allocations (% of spending in each category)

- survey profiles where we care about pattern, not absolute intensity

Distance and similarity: categorical / set data

Not all data are numerical vectors.

We can still define “difference” for:

- strings

- categorical vectors

- sets of items

Hamming and Levenshtein distances

Hamming distance

- number of positions where two strings differ

- requires equal length

Example: cat vs car → distance = 1 (only last letter differs)

Useful for:

- fixed-length codes

- yes/no voting records (Y/N sequences)

Levenshtein (edit) distance

- minimum number of insertions, deletions, or substitutions to turn one string into another

Example: kitten → sitting = 3 edits

Useful for:

- spell checking

- DNA / protein sequence comparison

- comparing policy text or legal clauses

Jaccard similarity for sets

For sets A and B:

\[ J(A,B) = \frac{|A \cap B|}{|A \cup B|} \]

- 1 → identical sets

- 0 → no overlap

Example: UN voting:

- A = set of resolutions Country A voted “Yes” on

- B = set of resolutions Country B voted “Yes” on

Then J(A,B) tells you:

- how similar their voting behaviour is

- regardless of how many total resolutions there are

Example:

Country A votes YES: {Res 1, 3, 5, 7}

Country B votes YES: {Res 1, 3, 6, 8}

Overlap: {1, 3} = 2

Union: {1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8} = 6

Jaccard = 2/6 = 0.33Useful for:

- co-sponsorship patterns

- shopping baskets

- sets of hashtags or liked pages

- document keyword sets

Distance metrics: summary

| Metric | Data type | Idea | Typical uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Euclidean | Continuous | Straight-line distance | Geometric data, numeric indicators |

| Manhattan | Continuous | Grid / city-block distance | Robust to outliers, discrete steps |

| Cosine similarity | Continuous | Angle (pattern) | Text, proportions, spending profiles |

| Hamming | Categorical | Mismatched positions | Voting records, fixed-length codes |

| Levenshtein | Strings | Edits needed to match | Text, DNA, version differences |

| Jaccard | Sets | Overlap / union | Co-occurrence, basket analysis, tags, keywords |

Key point: your choice of metric defines what “similar” means and therefore shapes the clusters and anomalies you discover.

From distance to density

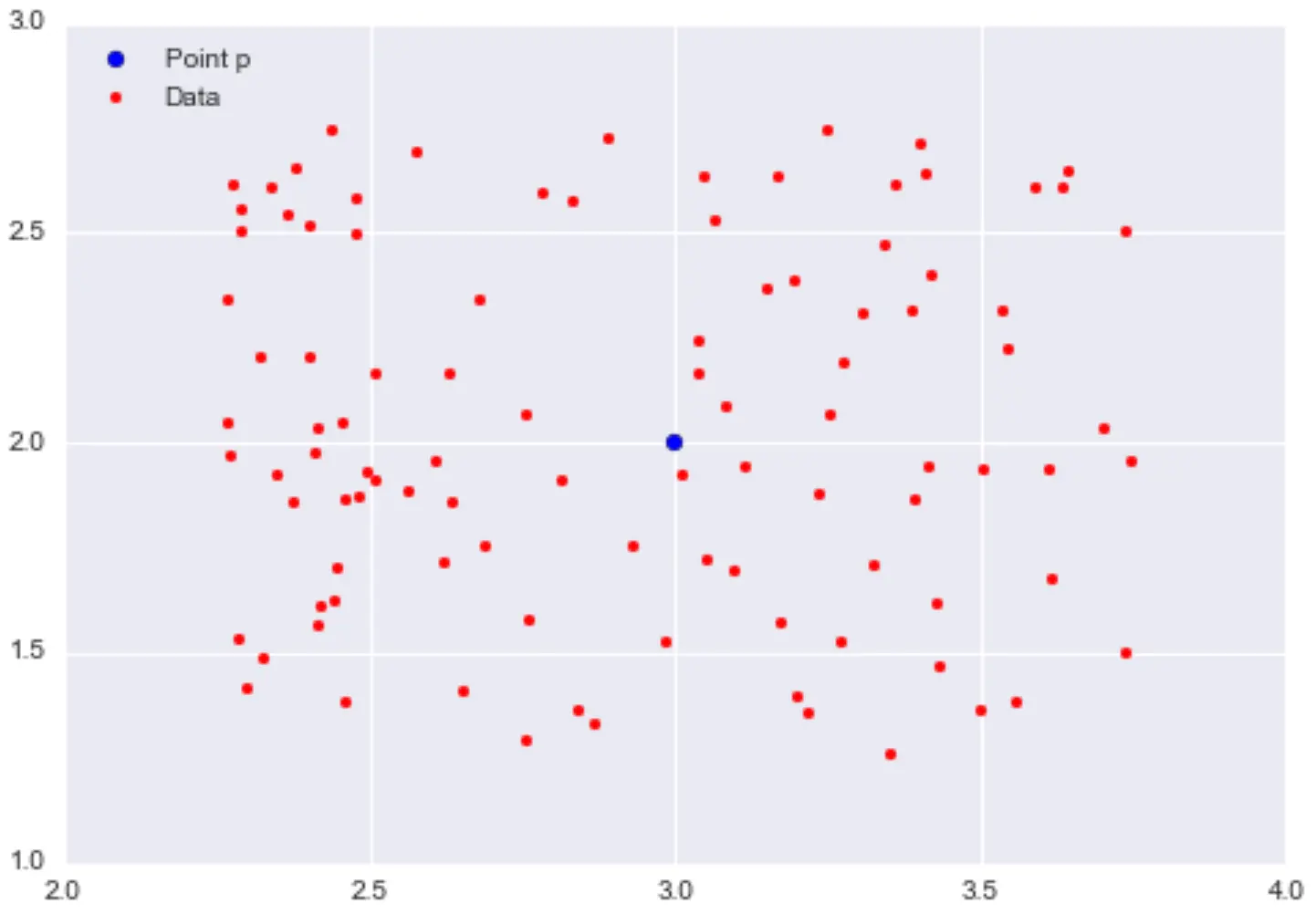

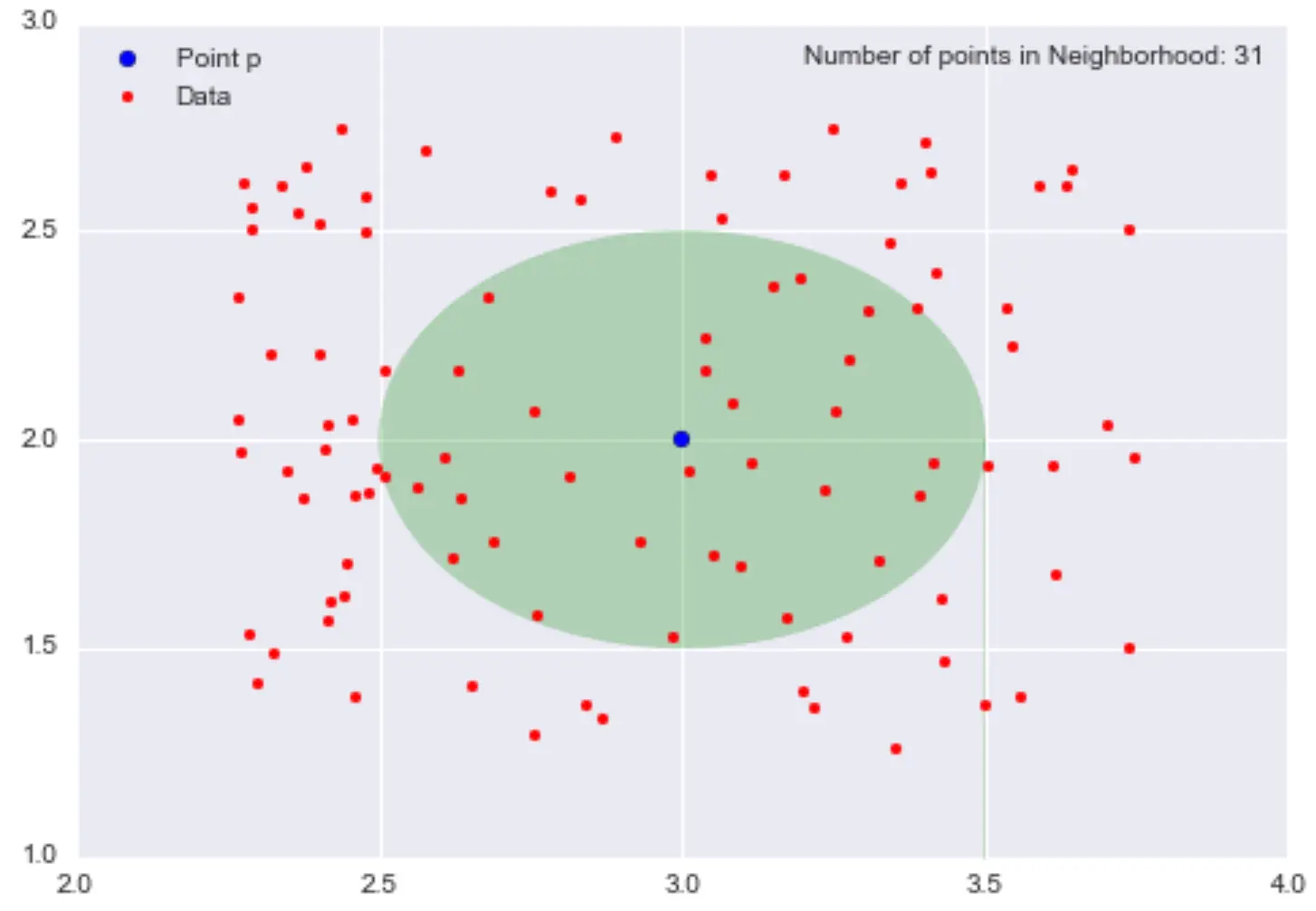

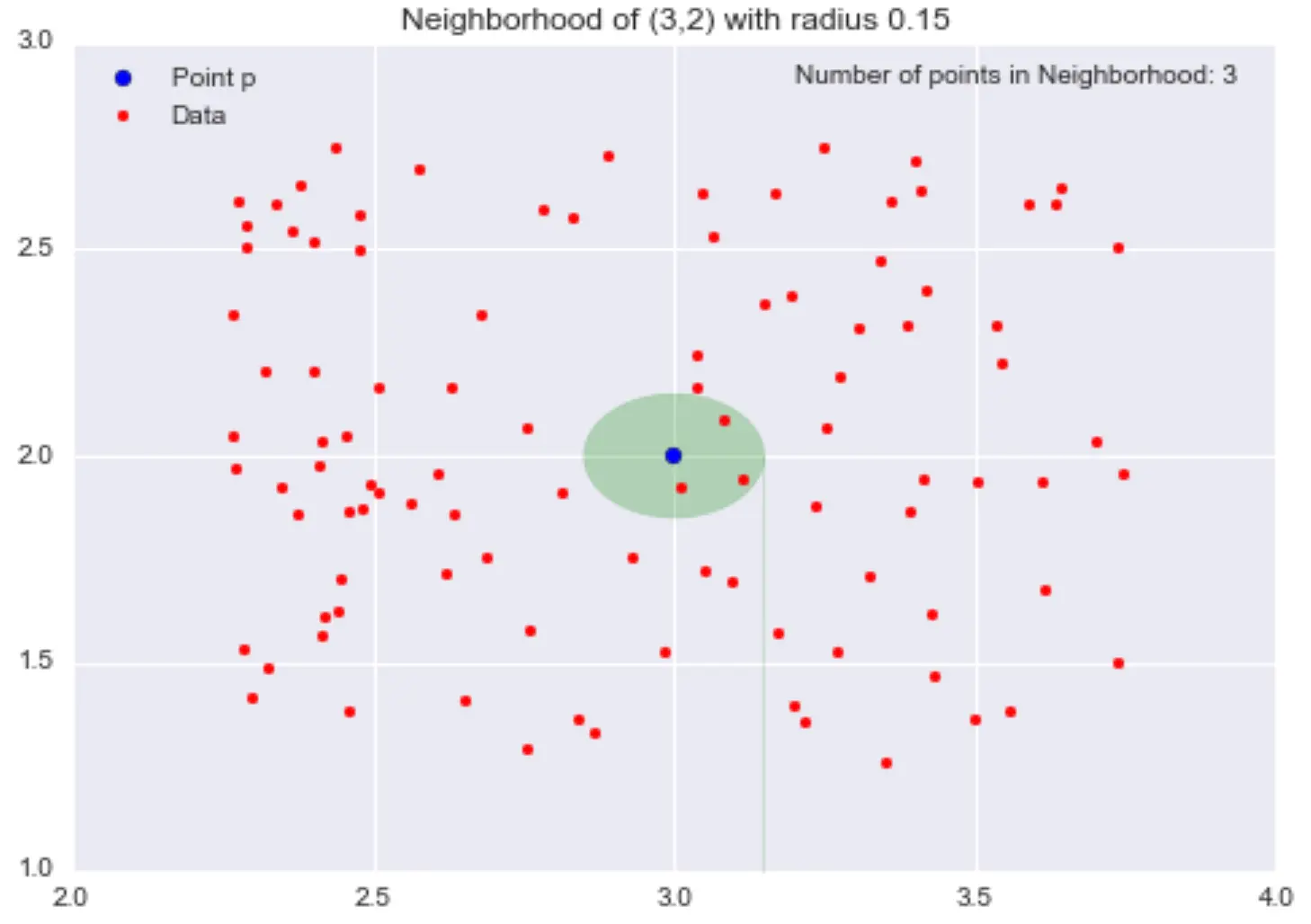

From pairwise distances to neighbourhoods

Distance tells us how far apart two points are.

We can extend this idea to:

How many neighbours does a point have within some radius?

Define the ε-neighbourhood of a point p as:

all points whose distance from p is less than ε.

Visualising ε-neighbourhoods

- With larger ε, each point has more neighbours

- With smaller ε, each point has fewer neighbours

We can think of:

density = number of points / volume (or area)

Why density matters for clustering

Intuition:

Points in high-density regions often belong to the same cluster

Points in low-density regions may be:

- between clusters

- or outliers

Some algorithms (like DBSCAN) are built entirely around:

- ε (neighbourhood radius)

- min_samples (minimum points to be a dense region)

We’ll return to this when we reach DBSCAN.

The K-means algorithm

Introduction

One of the most popular clustering algorithms: K-means.

The name:

- K = number of clusters (chosen by you)

- Means = cluster centres are means (centroids) of their points

Basic idea:

- Decide on K.

- Pick K initial centres (randomly or with a smart initialisation).

- Assign each point to the nearest centre (using a distance metric).

- Recompute each centre as the mean of its assigned points.

- Repeat steps 3–4 until assignments stop changing (converged).

K-means vs SVM (connecting back to supervised)

SVM (supervised):

- Given: data and labels

- Goal: find a boundary separating classes

- Uses distance to maximise the margin between classes

K-means (unsupervised):

- Given: data without labels

- Goal: find clusters + centres

- Uses distance to minimise within-cluster spread

Same tool (distance), different objective.

K-means objective

K-means tries to minimise the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS):

\[ \min_{C_1,\dots,C_K} \sum_{i=1}^K \sum_{x \in C_i} \lVert x - \mu_i \rVert^2 \]

where:

- \(C_i\) = cluster \(i\)

- \(\mu_i\) = mean (centroid) of cluster \(i\)

In words:

“Choose centres so that points are as close as possible to their cluster centre, on average.”

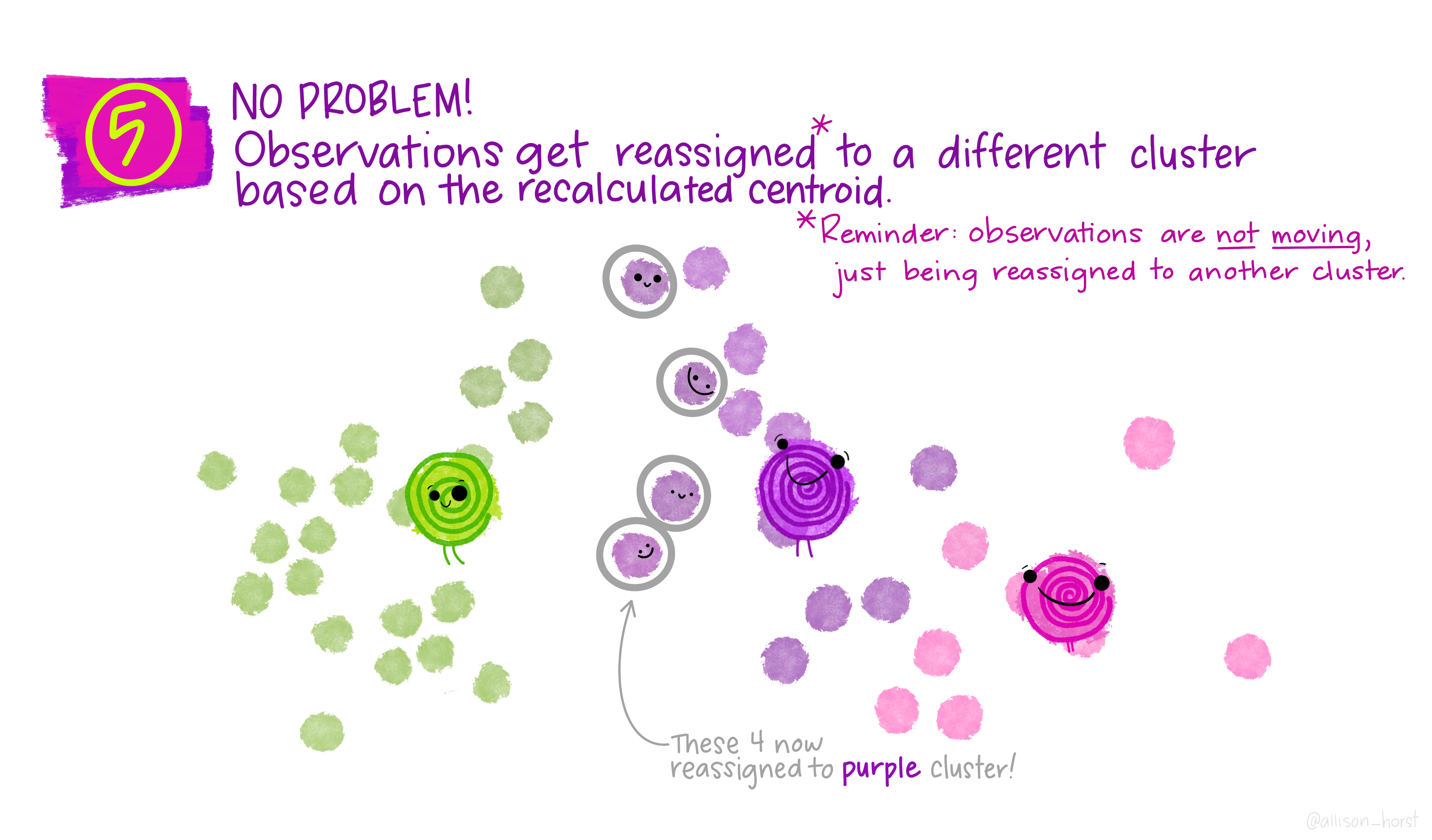

K-means: visual walkthrough

A live demo: see here

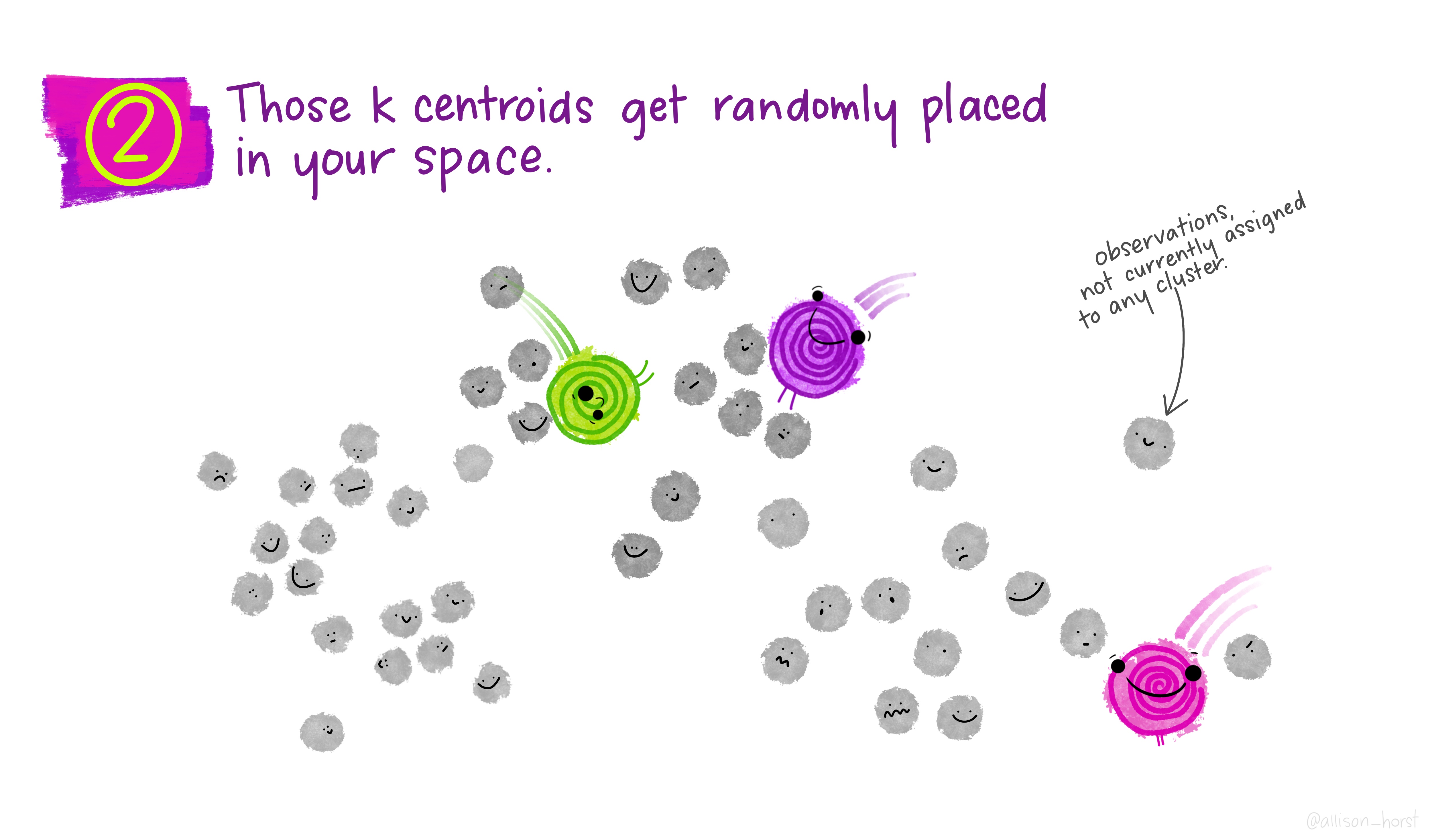

Step 1: choose K

Step 2: initialise centroids

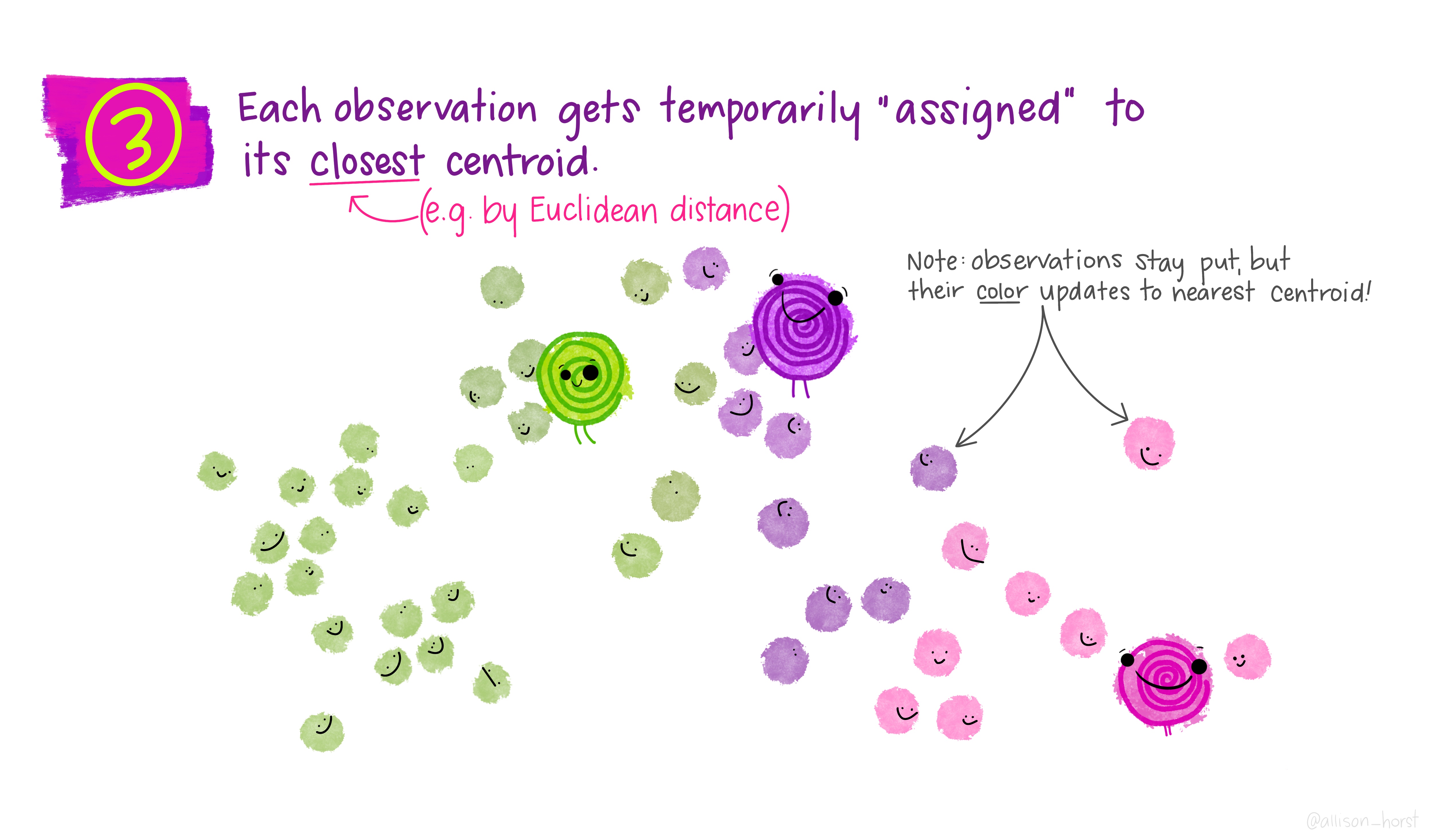

Step 3: assign to nearest centroid

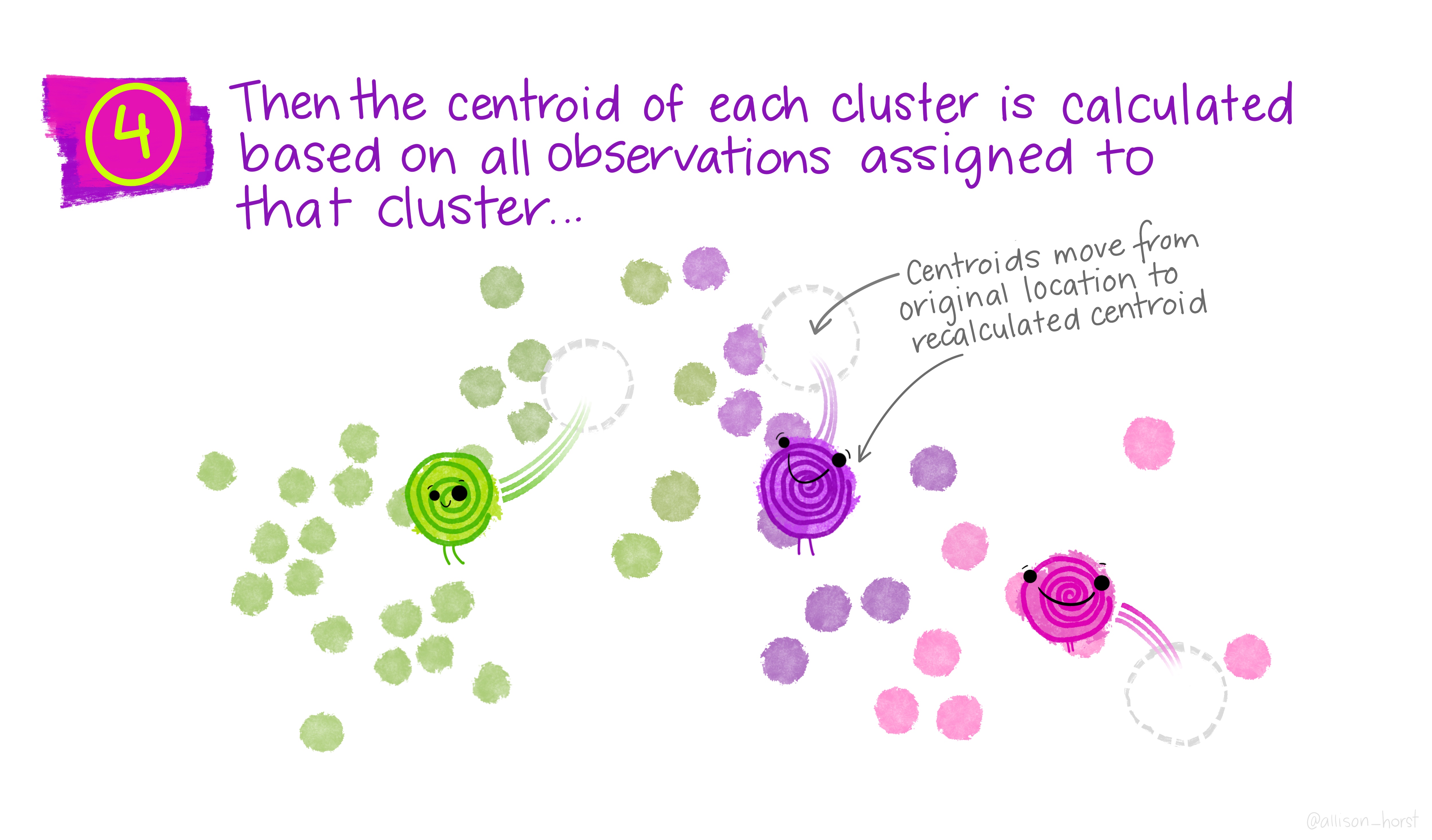

Step 4: recompute centroids

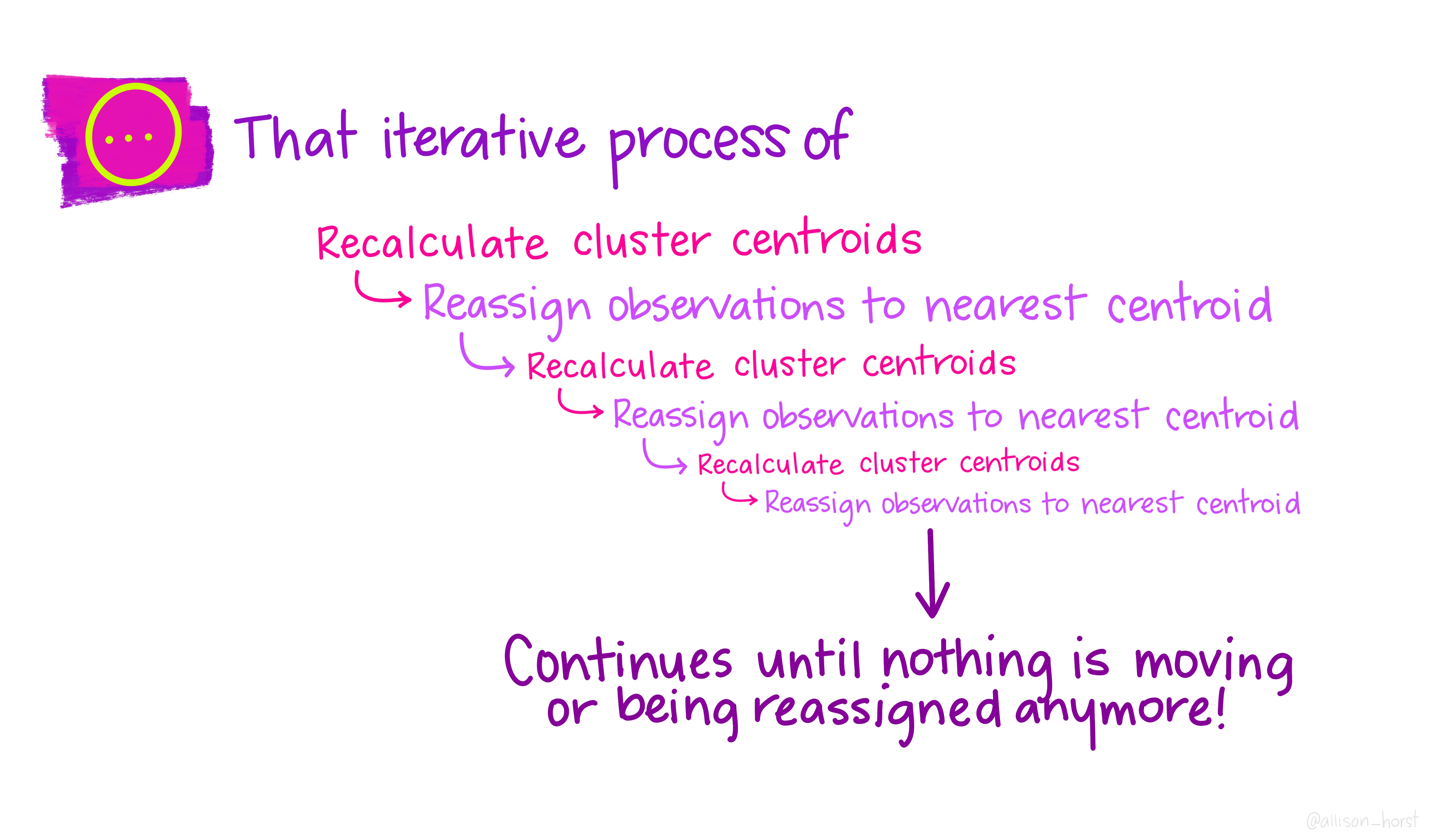

K-means: iteration

Assignments change, then centres update, then assignments change, etc.

K-means: convergence

K-means convergence

Eventually:

- assignments stop changing

- centroids stabilise

K-means is guaranteed to converge, although not always to the global best solution.

Strengths and limitations of K-means

Strengths:

- conceptually simple

- computationally efficient (even for large datasets)

- easy to interpret (cluster centres)

- widely available (built into many libraries)

Limitations:

- \(K\) (number of clusters) must be chosen in advance

- sensitive to initial centroids

- assumes roughly spherical, equal-sized clusters

- can be distorted by outliers

- struggles with complex shapes (e.g., concentric circles, “smiley face”)

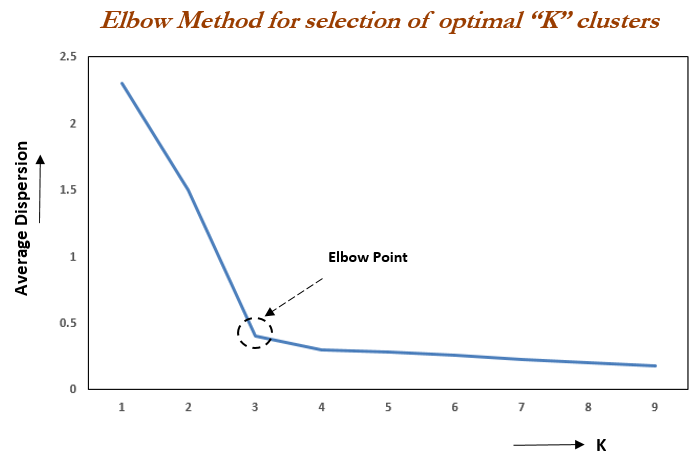

Choosing K: the elbow method

One popular heuristic:

- Run K-means for different values of \(K\) (e.g., 1 to 10).

- For each K, compute WCSS.

- Plot WCSS vs K.

- Look for an “elbow”: a point where the curve bends and extra clusters give diminishing returns.

Caveats about the elbow method

Real datasets often give:

- a smooth curve with no obvious elbow

- multiple potential elbows

- different answers depending on scaling, distance metric, etc.

Other approaches to choosing K:

- Silhouette score: how well separated clusters are

- Gap statistic: compare WCSS to what you’d get under a null (random) model

- Model-based methods: e.g., Gaussian Mixture Models with BIC/AIC

- Domain knowledge: how many clusters make sense substantively?

See this link or this link for more approaches to determine \(k\)

Important message: K-means is simple and useful, but choosing \(K\) is an art + science process.

Better initialisation: K-means++

Problem:

- random initial centroids can yield poor solutions

- sensitive to unlucky starts

K-means++ (see original paper (Arthur and Vassilvitskii 2007)):

- Choose the first centroid at random.

- Choose subsequent centroids, preferring points far from existing centroids (probability proportional to distance²).

- Then run standard K-means.

Benefits:

- better starting points

- faster convergence

- often better final clustering

Most modern implementations (e.g. scikit-learn) use K-means++ by default.

DBSCAN and density-based clustering

Why we need an alternative

K-means:

assumes roughly spherical clusters

forces every point into a cluster

struggles with:

- irregular shapes

- variable densities

- meaningful outliers

We need methods that can:

- find clusters of arbitrary shape

- treat some points as noise/outliers

A live demo: see here

DBSCAN: core idea

DBSCAN = Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise.

Parameters:

- ε (epsilon): neighbourhood radius

- min_samples: minimum number of points in an ε-neighbourhood to be “dense”

Concepts:

- Core point: has ≥ min_samples neighbours within ε

- Border point: not dense enough itself, but close to a core point

- Noise point: neither core nor border (outlier)

Algorithm (informally):

- Find all core points.

- Connect core points that are close to each other → form clusters.

- Assign nearby border points to these clusters.

- Label remaining points as noise.

Clusters correspond to regions of high density, separated by low-density regions.

If you want more details, you can have a look at the original DBSCAN paper (Ester et al. 1996).

DBSCAN vs K-means

| Aspect | K-means | DBSCAN |

|---|---|---|

| # of clusters | Must choose K | Determined by data (via ε, min_samples) |

| Cluster shape | Spherical blobs (roughly) | Arbitrary shapes |

| Outliers | Forced into some cluster | Can be labelled as noise |

| Parameters | K | ε, min_samples |

| Best for | Simple, compact clusters | Clusters of varying shape + noise |

DBSCAN is particularly powerful when:

- clusters follow irregular geometries

- there is important noise or outliers

- we care about identifying anomalous points as well as clusters

Live demo: clustering countries

Demo overview

We return to our development dataset:

- ~170 countries

- 20+ indicators (economic, governance, health, education, etc.)

Questions:

- How many distinct development “types” emerge?

- Is the old “developed vs developing” dichotomy too simple?

- Which countries are outliers in their region or income group?

We will:

- standardise indicators

- apply K-means

- experiment with different K

- then try DBSCAN to see if it finds different shapes or outliers

Download materials

You will be able to experiment yourself using:

Wrap-up

What we learned today (unsupervised part)

Many real-world problems don’t come with labels.

Unsupervised learning helps us:

- discover groups (clustering)

- find co-occurrence patterns (association rules)

- simplify high-dimensional data (dimensionality reduction)

- detect unusual cases (anomaly detection)

All these methods rely on a notion of similarity/distance.

Choosing the right distance metric is crucial.

We studied K-means in detail and introduced DBSCAN as a density-based alternative.

Key takeaways

Labels are expensive, incomplete, or unavailable in many domains.

Unsupervised learning lets us explore structure before committing to labels.

Clusters and patterns are hypotheses, not ground truth.

The choice of:

- features

- distance metric

- algorithm

- parameters all shape the patterns you see.

Domain knowledge is essential to interpret and validate unsupervised results.

Looking ahead

This week: Countries + numbers → unsupervised methods on tabular data.

Next week: Documents + words:

Representing text as numbers (bag-of-words, TF–IDF)

Using similarity & clustering for:

- topic discovery

- grouping news articles

- basic text mining

The same ideas — distance, clusters, anomalies — will carry over, just on a new type of data.

Questions?

Thank you!

Reflect on how your own research area might use unsupervised learning.

Think about:

- what “similarity” means in your context

- which unsupervised family might be most useful

See you next week for text mining and unstructured data.

References

LSE DS101 2025/26 Autumn Term