🗓️ Week 07

Machine Learning I

DS101 – Fundamentals of Data Science

10 Nov 2025

⏪ Recap

- A model is a mathematical representation of a real-world process, a simplified version of reality.

- We saw examples of linear regression models (week 5 lecture and class).

- It contains several assumptions that need to be met for the model to be valid.

- Social scientists have been using linear regression models for decades.

⏪ Recap: Linear Regression

We also saw how linear regression models are normally represented mathematically:

The generic supervised model:

\[ Y = \operatorname{f}(X) + \epsilon \]

is defined more explicitly as follows ➡️

Simple linear regression

\[ \begin{align} Y = \beta_0 +& \beta_1 X + \epsilon, \\ \\ \\ \end{align} \]

when we use a single predictor, \(X\).

Multiple linear regression

\[ \begin{align} Y = \beta_0 &+ \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 \\ &+ \dots \\ &+ \beta_p X_p + \epsilon \end{align} \]

when there are multiple predictors, \(X_p\).

Note

- As a well-studied statistical technique, we know a lot about the properties of the model.

- Researchers can use this knowledge to assess the validity of the model, using things like confidence intervals, hypothesis testing, and many other model diagnostics.

Limitations of Linear Regression Models

The typical linear model assumes that:

- the relationship between the response and the predictors is linear.

- the error terms are independent and identically distributed.

- the error terms have a constant variance.

- the error terms are normally distributed.

Important

Barely any real-world process is linear.

Making Predictions

We often want to use a model to make predictions

- either about the future

- or about new observations.

Linear regression is not always the way to go

Linear regression is powerful — but it’s not magic.

Sometimes, the world is more complicated than a single straight line.

Linear regression works well for continuous numeric outcomes, but what about:

- Categorical outcomes? (yes/no, success/failure, Category A/B/C)

- Non-linear relationships? (curved patterns, thresholds)

- Complex patterns? (interactions between many features)

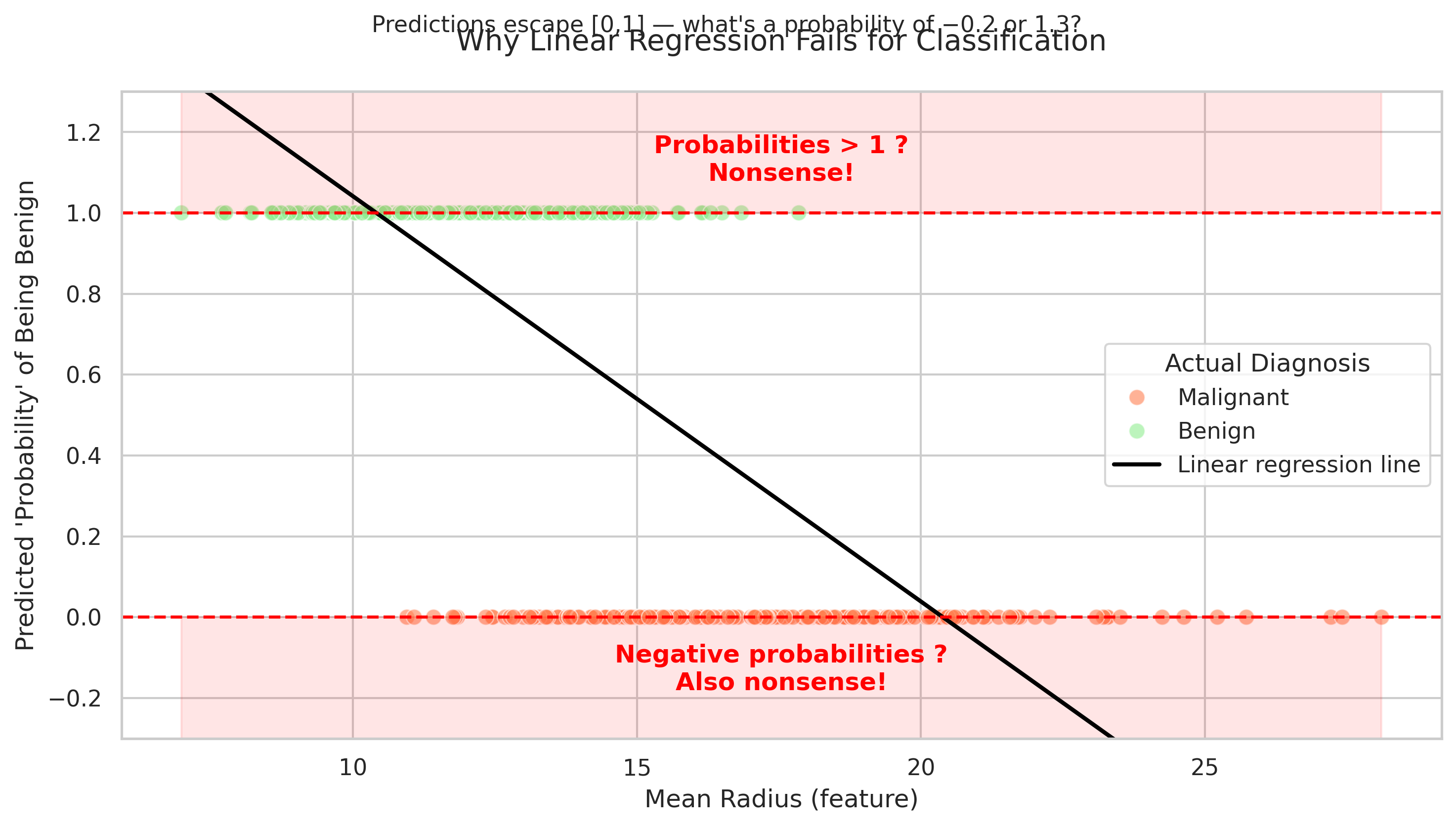

🩺 Binary/categorical outcomes: The Breast Cancer Dataset

Linear regression predicts continuous outcomes — like price, height, or temperature. But what happens when the target is Yes/No?

Note

Linear regression assumes continuous change — but here, the outcome is either 0 or 1 (benign or malignant).

Trying to “fit a line” between two categories can lead to impossible values like probabilities below 0 or above 1. Linear regression doesn’t know probabilities must be between 0 and 1. Here, small tumors lead to predicted probabilities below 0, large ones above 1.

We’ll need another model type for this later — logistic regression.

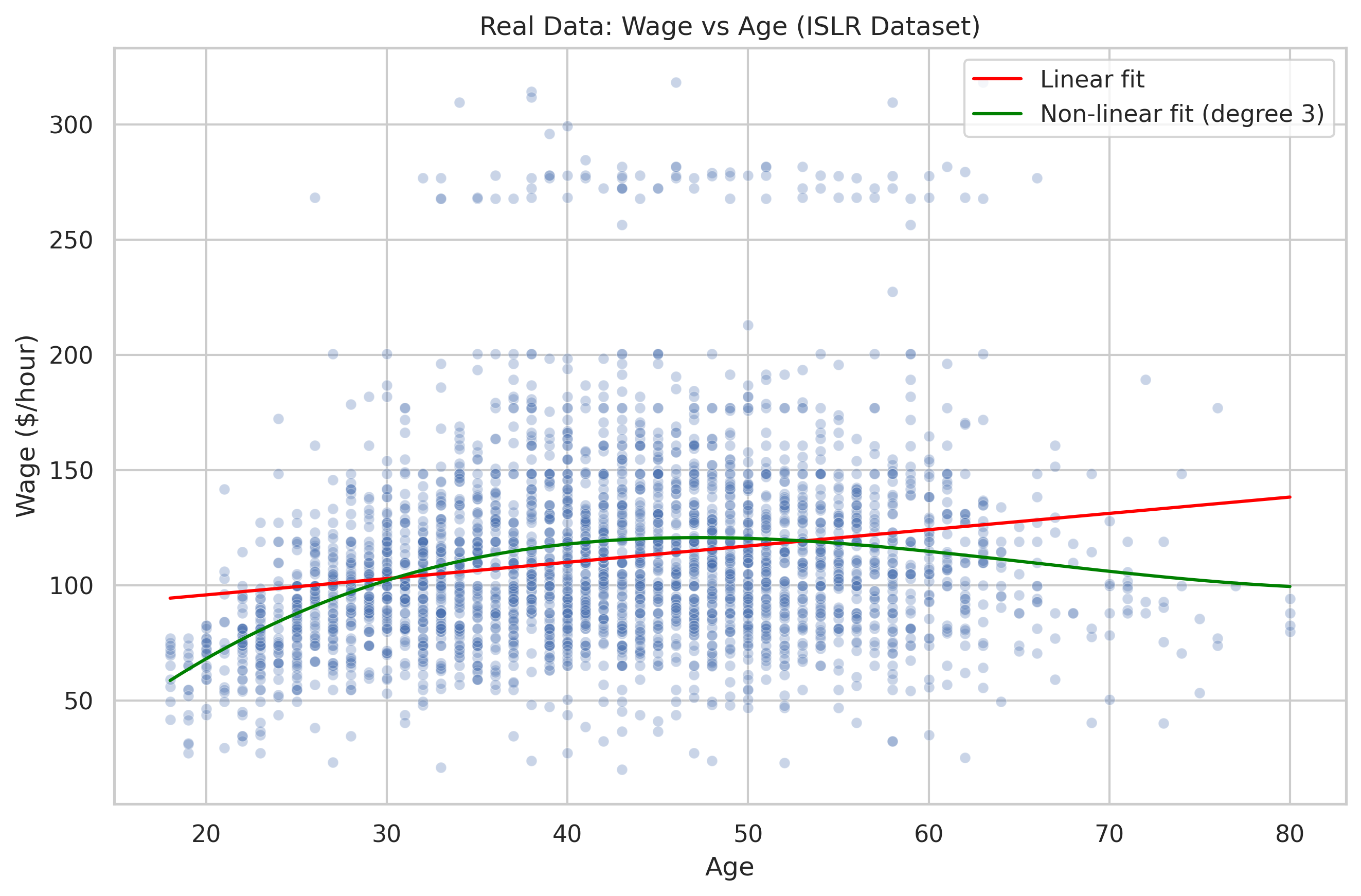

Non-Linear Patterns: The Wage Dataset

Now let’s look at a real dataset: wage and age from the ISLR book.

Note

Real data shows diminishing returns — wages rise, then flatten, and sometimes fall slightly. The real data reveals curvature: wages rise rapidly early in careers, then plateau and sometimes decline.

Linear regression assumes a constant slope: every extra year of age increases wage by the same amount. It draws a single straight line — it misses the curve.

That’s why we later use polynomial regression or other flexible methods. This shows that a straight line is too simple for curved, real-world data.

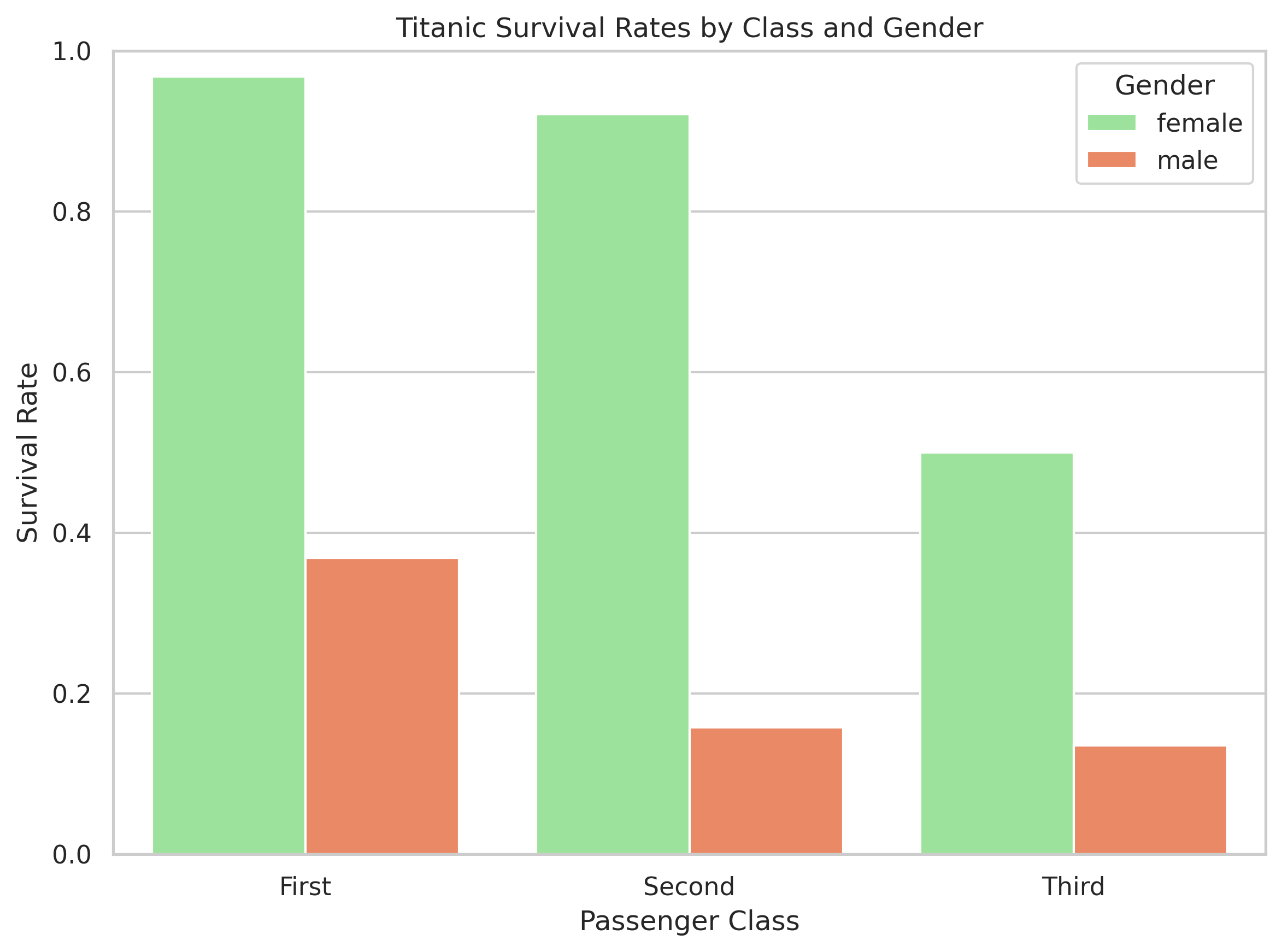

Interactions: Titanic Survival

Sometimes, even if variables look simple individually, their combination tells the real story.

Note

Linear regression assumes each variable contributes a fixed, independent effect. But here, the effect of gender changes by class:

- Women in 1st and 2nd class mostly survived.

- In 3rd class, the difference shrinks a lot.

A single “gender coefficient” can’t capture that. This is what we call an interaction — the effect of one variable depends on another.

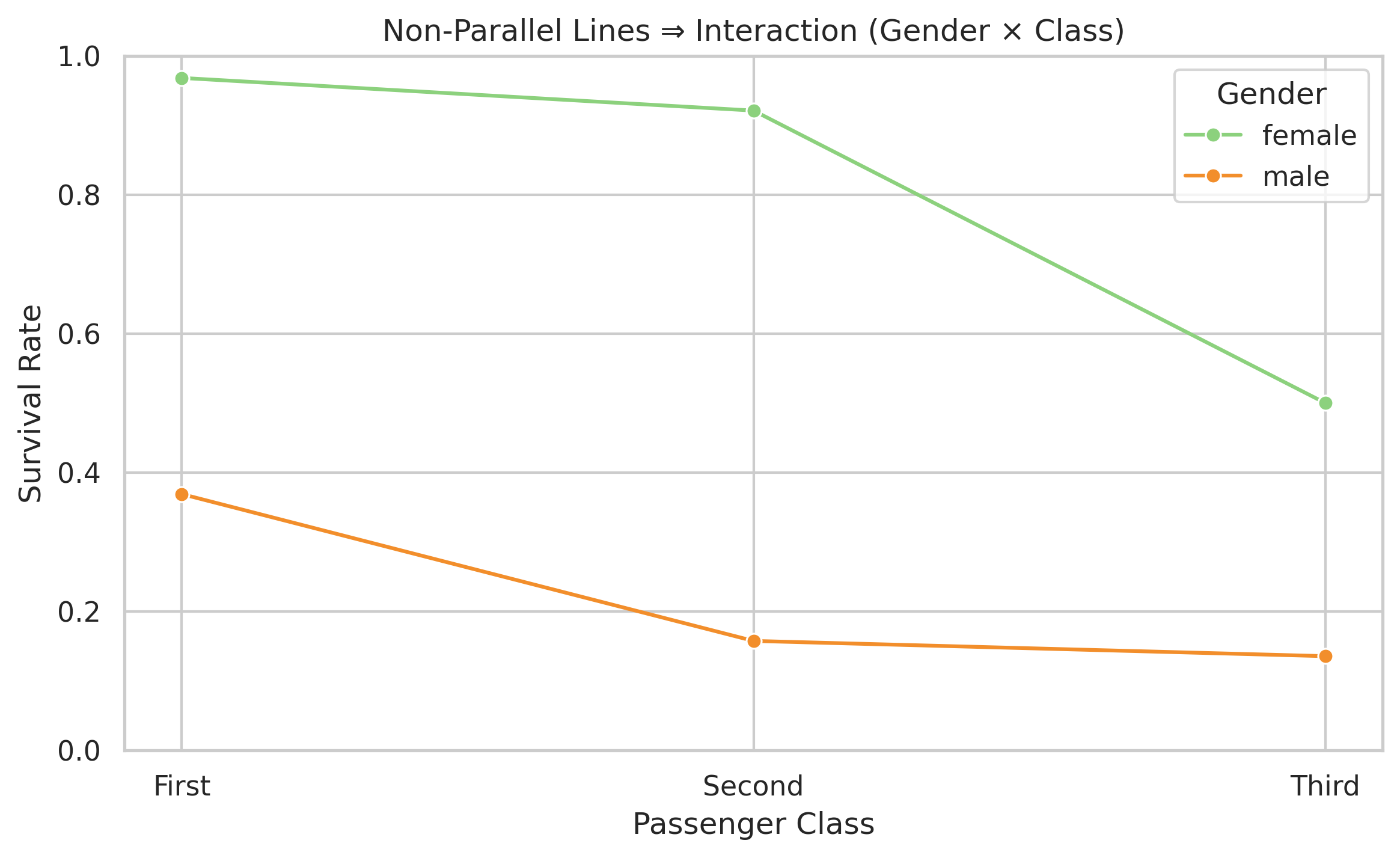

Titanic: non-parallel lines show interactions clearly

Note

If there were no interaction, the lines would be parallel. But they’re not — the “female advantage” shrinks as class drops. Linear regression would try to average across both and get it wrong.

Summary

Linear regression struggles when:

| Situation | Why it fails |

|---|---|

| Binary outcomes | Predictions can go below 0 or above 1 |

| Non-linear patterns | A single straight line can’t follow curves |

| Interactions | One “average slope” can’t fit all groups |

Linear regression is like a ruler — powerful, simple, but only straight. The real world isn’t always linear.

Note

We need more flexible tools for prediction. Enter Machine Learning.

What is Machine Learning?

A definition

Machine Learning (ML) is a subfield of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence (AI) that focuses on the design and development of algorithms that can learn from data.

How it works

How it works

- The process is similar to the regular algorithms (think recipes) we saw in W03.

- Only this time, the ingredients are data.

INPUT (data)

⬇️

ALGORITHM

⬇️

OUTPUT (prediction)

Types of Machine Learning

Supervised

Learning

- Each data point is associated with a label.

- The goal is to learn a function that maps the data to the labels.

(🗓️ Week 07 - today!)

Unsupervised

Learning

- There is no such association between the data and the labels.

- The focus is on similarities between data points.

(🗓️ Week 08)

Supervised Learning

Supervised Learning

If we assume there is a way to map between X and Y, we could use SUPERVISED LEARNING to learn this mapping.

Supervised Learning

- The algorithm will teach itself to identify changes in \(Y\) based on the values of \(X\)

- A dataset of labelled data is required

- Prediction: presented with new \(X\), the algorithm will be able to predict how \(Y\) would be like

Supervised Learning

- If \(Y\) is a numerical value, we call it a regression problem.

- If \(Y\) is a category, we call it a classification problem.

Supervised Learning

- There are countless ways to do that; each algorithm does it in its own way.

- Here are some names of basic algorithms:

- Linear regression

- Logistic regression

- Decision trees

- Support vector machines

- Neural networks

One Practical Example

Suppose you’re a record executive at a major label. Two artists pitch you new songs. You can only invest your marketing budget in one.

Image source: Unsplash

How would you decide which song will be a hit?

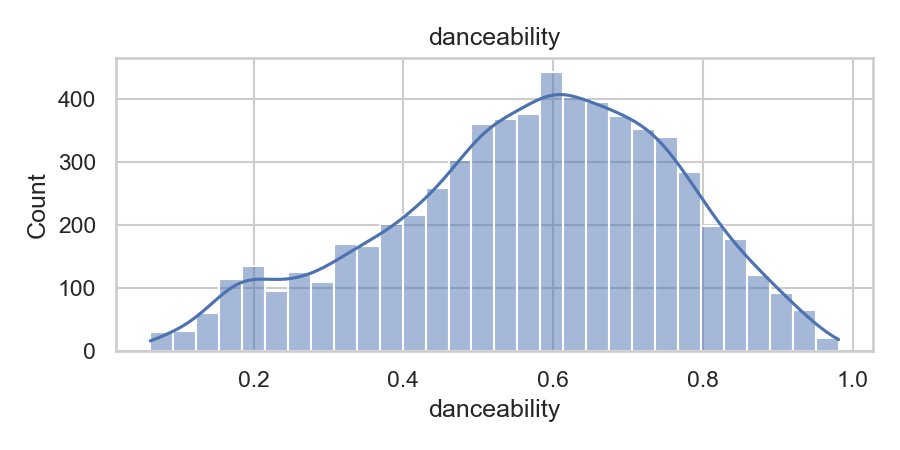

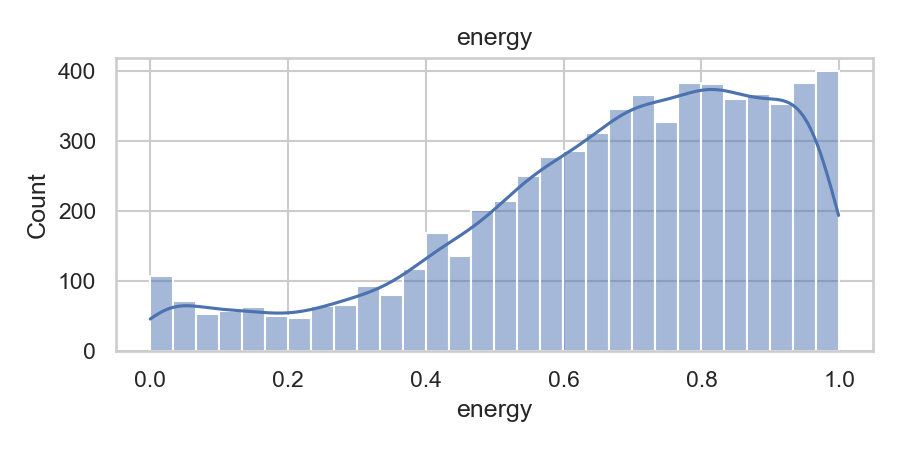

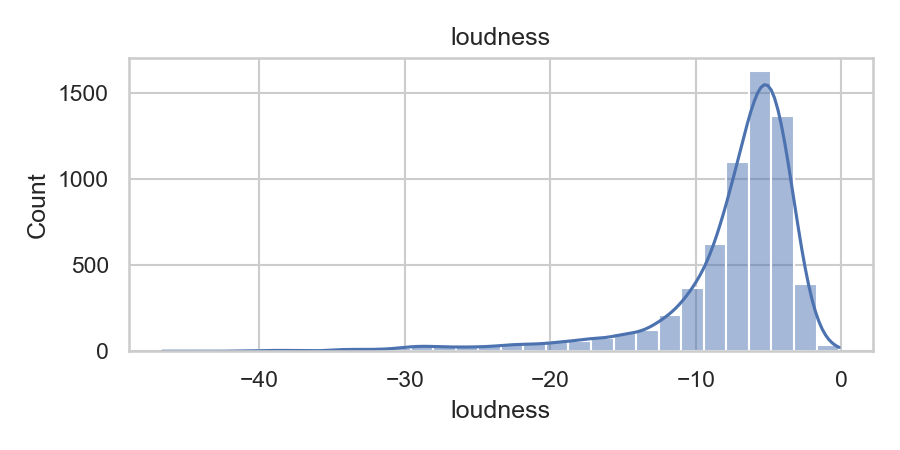

What features could help us predict hits?

If we try to predict whether a song will chart on Billboard Hot-100, we could look at:

- Danceability (0-1): How suitable is it for dancing based on tempo, rhythm, and beat?

- Energy (0-1): How intense and active does it feel?

- Valence (0-1): Does it sound happy (high) or sad (low)?

- Tempo: Beats per minute (BPM)

- Loudness: Overall volume in decibels

- Speechiness (0-1): How much spoken word vs singing?

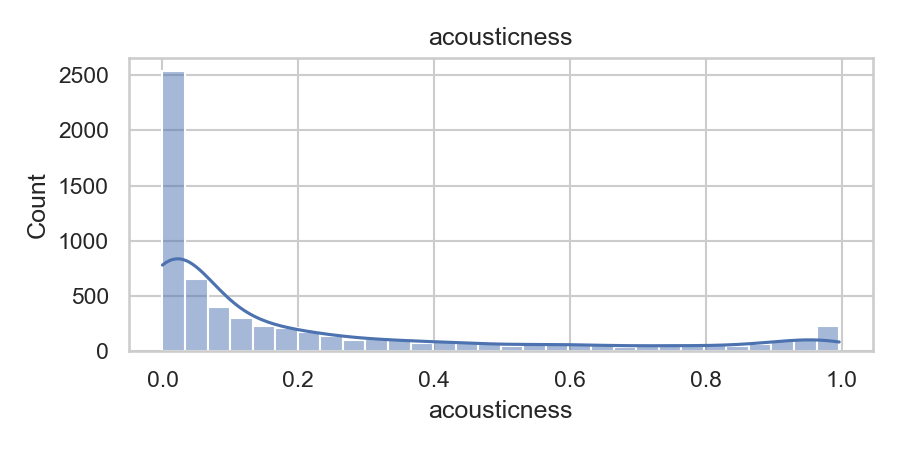

- Acousticness (0-1): Is it acoustic or electronic?

- Instrumentalness (0-1): Vocals or purely instrumental?

- Liveness (0-1): Was it recorded with an audience?

- Duration: How long is the song (in milliseconds)?

- Time signature: 4/4 time? 3/4?

All of this information constitutes our input (features extracted from Spotify’s API). You can find the dataset on Kaggle.

A quick look at the data features

What about the output?

- The output is something you would normally want to predict or attempt to explain 1

- Also referred to as the label, “ground truth”, target or dependent variable, or simply \(Y\)

- In our case: Did the song become a Hit or a Flop?

- Hit = appeared on Billboard’s Weekly Hot-100 chart

- Flop = never charted

- This is a binary classification problem

Structure of dataset

| index | track | artist | uri | danceability | energy | key | loudness | mode | speechiness | acousticness | instrumentalness | liveness | valence | tempo | duration_ms | time_signature | chorus_hit | sections | target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Wild Things | Alessia Cara | spotify:track:2ZyuwVvV6Z3XJaXIFbspeE | 0.741 | 0.626 | 1 | -4.826 | 0 | 0.0886 | 0.02 | 0.0 | 0.0828 | 0.706 | 108.029 | 188493 | 4 | 41.18681 | 10 | 1 |

| 1 | Surfboard | Esquivel! | spotify:track:61APOtq25SCMuK0V5w2Kgp | 0.447 | 0.247 | 5 | -14.661 | 0 | 0.0346 | 0.871 | 0.814 | 0.0946 | 0.25 | 155.489 | 176880 | 3 | 33.18083 | 9 | 0 |

| 2 | Love Someone | Lukas Graham | spotify:track:2JqnpexlO9dmvjUMCaLCLJ | 0.55 | 0.415 | 9 | -6.557 | 0 | 0.052 | 0.161 | 0.0 | 0.108 | 0.274 | 172.065 | 205463 | 4 | 44.89147 | 9 | 1 |

| 3 | Music To My Ears (feat. Tory Lanez) | Keys N Krates | spotify:track:0cjfLhk8WJ3etPTCseKXtk | 0.502 | 0.648 | 0 | -5.698 | 0 | 0.0527 | 0.00513 | 0.0 | 0.204 | 0.291 | 91.837 | 193043 | 4 | 29.52521 | 7 | 0 |

| 4 | Juju On That Beat (TZ Anthem) | Zay Hilfigerrr & Zayion McCall | spotify:track:1lItf5ZXJc1by9SbPeljFd | 0.807 | 0.887 | 1 | -3.892 | 1 | 0.275 | 0.00381 | 0.0 | 0.391 | 0.78 | 160.517 | 144244 | 4 | 24.99199 | 8 | 1 |

- The data shown is from the Spotify Hit Predictor Dataset (Kaggle)

- Dataset contains 40,000+ songs from 1960–2019

- All features extracted using Spotify’s Web API

- Target labels based on Billboard Hot-100 chart performance

Let’s listen to some examples 🎧

A hit example (High danceability, energy, valence)

- “Shake It Off” - Taylor Swift (2014)

- Danceability: 0.648, Energy: 0.785, Valence: 0.943

One flop example (Lower scores, less mainstream appeal)

- “Coming home” - Leon Bridges (2015): it evokes 1960s soul warmth but scores low on Spotify hit predictors — low danceability (0.427), low energy (0.465), rather high acousticness (0.461).

A beautiful song, but not built for the algorithmic dance floor.

Some (supervised) machine learning algorithms

From “Hit or Flop?” to Logistic Regression

Let’s say our response is binary — a song either hits 🎯 or flops 💀:

\[ Y = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{= Flop} \\ 1 & \text{= Hit} \end{cases} \]

We want to model how the probability of a hit changes with some feature (e.g., energy, danceability).

→ Instead of predicting 0 or 1 directly,

we predict a probability between 0 and 1 using the logistic (sigmoid) function:

\[ P(Y = 1 \mid X) = p(X) = \frac{e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X}}{1 + e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X}} \]

🌀 As \(X\) increases, the curve smoothly transitions from near 0 (flop)

to near 1 (hit) — perfect for probabilities!

Source of illustration: TIBCO

Logistic regression: extending to multiple features

For one feature, we had:

\[ P(Y = 1 \mid X) = \frac{e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X}}{1 + e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X}} \]

With multiple predictors (e.g. danceability, energy, tempo…),

we simply add more terms inside the exponent:

\[ P(Y = 1 \mid X_1, X_2, ..., X_p) = \frac{e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_p X_p}} {1 + e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_p X_p}} \]

🧠 Think of it as:

- Combine all features into a weighted score

(\(z = \beta_0 + \beta_1X_1 + \dots + \beta_pX_p\)) - Pass that score through the logistic curve → gives a probability between 0 and 1.

🎯 Still interpretable:

- Each coefficient \(\beta_j\) shows how much that feature

pushes the probability of a hit up or down,

keeping others constant.

Logistic regression applied to our Spotify example

- Our dataset has numerical features (danceability, energy, valence, tempo, etc.)

- We’ll split the data: 70% training, 30% testing

- We’ll use all the features to predict Hit vs Flop

- The model will learn which features best predict chart success

Example: Splitting the Data

| Dataset | Portion | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 🎓 Training set | 70% of songs | Used to teach the model the relationship between features (danceability, energy, etc.) and outcomes (hit/flop). |

| 🧪 Test set | 30% of songs | Used after training to evaluate how well the model generalizes to unseen songs. |

🧠 Think of it like studying vs. taking the exam — the model “studies” on the training set and gets “tested” on the test set.

How do we evaluate the model’s performance?

Some key definitions:

We have two classes: Hit (positive class - what we’re interested in) and Flop (negative class)

Based on this, we can have four outcomes:

- True Positive (TP): A hit correctly predicted as a hit ✓

- True Negative (TN): A flop correctly predicted as a flop ✓

- False Positive (FP): A flop incorrectly predicted as a hit ✗

- False Negative (FN): A hit incorrectly predicted as a flop ✗

Question for the class: Which is worse for a record label?

- False Positive: Invest millions marketing a song the model predicted would be a hit, but it flops

- False Negative: Pass on a song the model predicted would flop, but it becomes a hit

Discussion point: Both are bad in different ways! False positives waste money, false negatives lose opportunity.

Evaluation Metrics

Accuracy: Overall, how often is the model correct? \[\text{Accuracy} = \frac{TP + TN}{TP + TN + FP + FN}\]

However, is 99% accuracy always good? No! That’s the “accuracy paradox”

- If 95% of songs are flops, a model that always predicts “Flop” gets 95% accuracy but is useless!

- Better metrics for classification:

Precision: Of songs we predicted would be hits, how many actually were? \[\text{Precision} = \frac{TP}{TP + FP}\]

Recall: Of actual hits, how many did we catch? \[\text{Recall} = \frac{TP}{TP + FN}\]

F1-Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall (balanced measure) \[\text{F1-score} = 2 \cdot \frac{\text{Precision} \cdot \text{Recall}}{\text{Precision} + \text{Recall}}\]

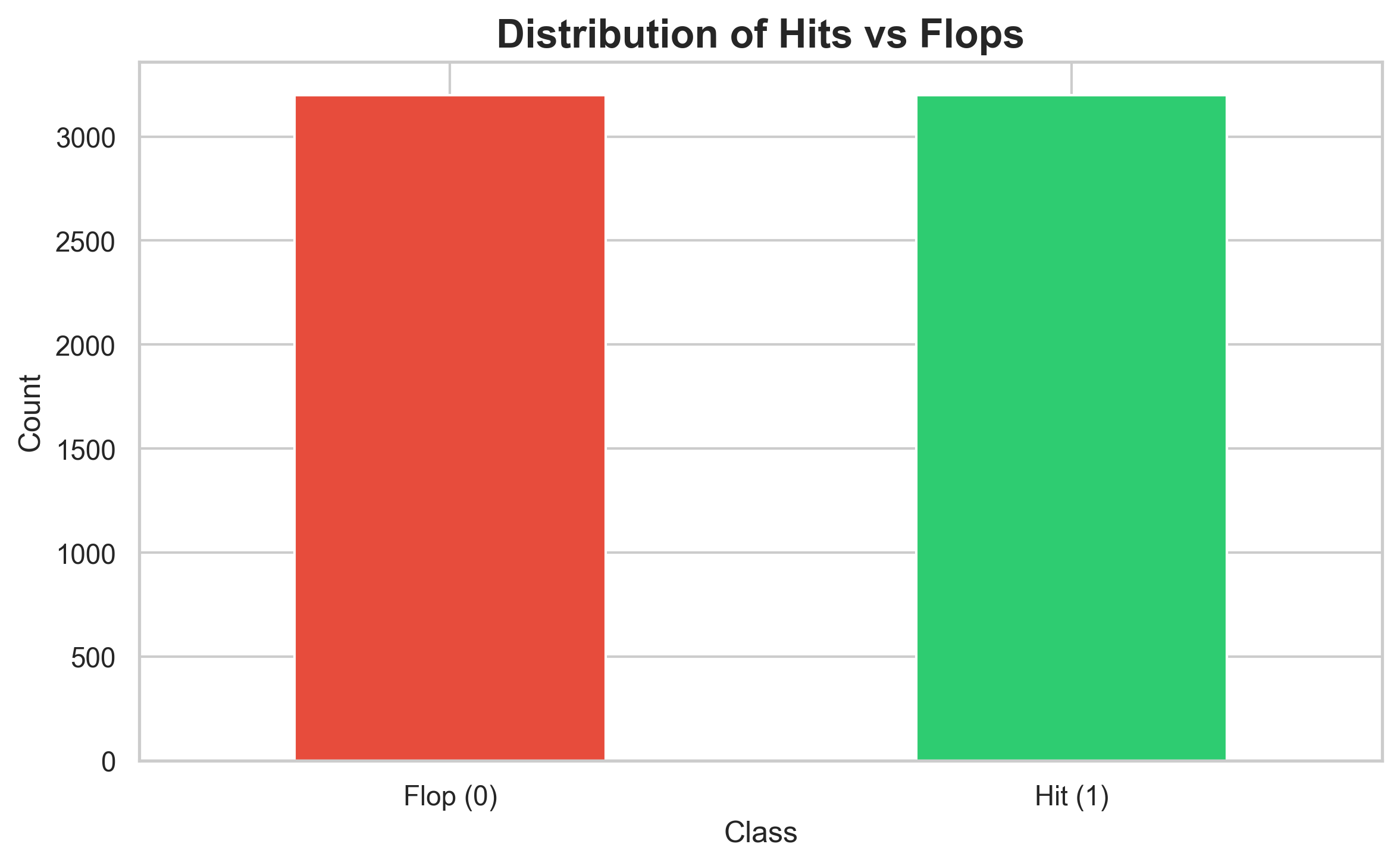

Dataset Balance

Let’s check our Spotify dataset:

---------------------------

Target value: Hit

Number of songs: 3,199

Proportion: 0.50

---------------------------

Target value: Flop

Number of songs: 3,199

Proportion: 0.50

---------------------------

Note

Good news! Our dataset is balanced (50-50 split). This means accuracy is actually a reasonable metric to use, though we’ll still look at precision, recall, and F1-score for a complete picture.

Logistic Regression Results

Model Performance:

Classification Report:

precision recall f1-score support

Flop 0.87 0.71 0.78 960

Hit 0.76 0.89 0.82 960

accuracy 0.80 1920

macro avg 0.81 0.80 0.80 1920

weighted avg 0.81 0.80 0.80 1920Interpretation:

✅ Model correctly classifies songs about 80% of the time

🎵 Better at catching hits (recall = 0.89) than flops (recall = 0.71)

⚖️ Precision trade-off:

- Predicts “Flop” → correct 87 % of the time

- Predicts “Hit” → correct 76 % of the time

🧠 Cautious model: under-predicts hits, over-predicts flops

💬 Would you trust this to spend millions in marketing?

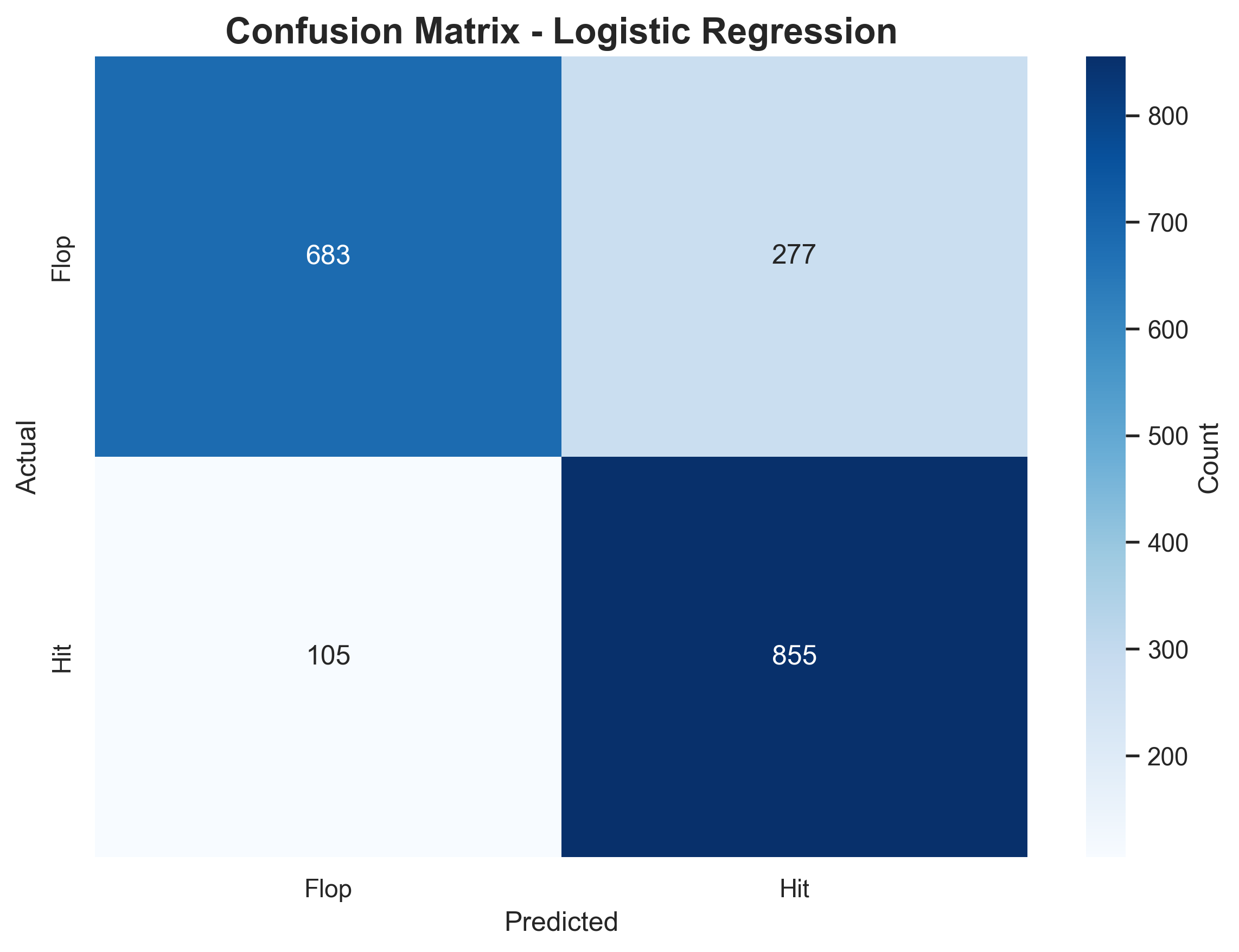

Confusion Matrix — Logistic Regression

How to read this:

| Term | Meaning | Spotify context |

|---|---|---|

| ✅ True Positives (855) | Predicted Hit → Actually Hit | Correctly spotted popular songs |

| ✅ True Negatives (683) | Predicted Flop → Actually Flop | Correctly dismissed weak songs |

| ⚠️ False Positives (277) | Predicted Hit → Actually Flop | 💸 Wasted promo budget on bad calls |

| ⚠️ False Negatives (105) | Predicted Flop → Actually Hit | 🎯 Missed breakout songs |

Takeaway:

- The model is risk-averse — safer but not visionary

- Would a record label prefer fewer false alarms or fewer missed hits?

Business Impact of Model Errors

| Prediction → | Flop | Hit |

|---|---|---|

| Actual: Flop | ✅ True Negative → No wasted budget |

⚠️ False Positive → 💸 Wasted marketing spend |

| Actual: Hit | ⚠️ False Negative → 🎯 Missed opportunity |

✅ True Positive → 💰 Promoted real hits |

Key question:

Which mistake costs more for a record label — spending money on a flop, or missing a song that could go viral?

Context matters:

Different stakeholders care about different errors:

- 💼 Finance teams hate false positives (money wasted).

- 🎵 A&R / marketing teams fear false negatives (missed talent).

Business context determines how we tune the model’s decision threshold.

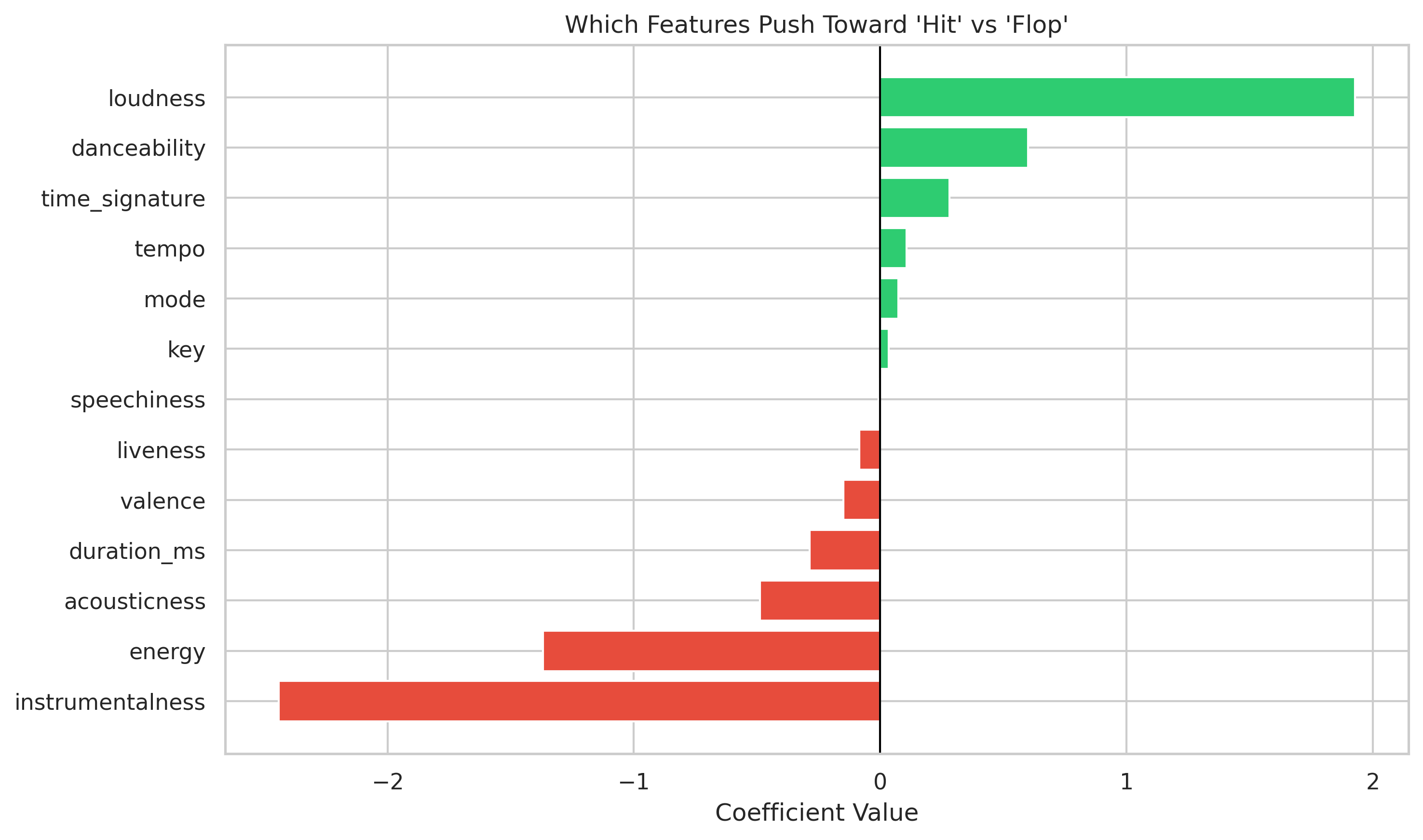

🎵 What Makes a Hit Song?

Tip

Understanding the chart:

Each bar shows how a musical feature influences the model’s prediction of whether a song becomes a Hit or Flop.

Green bars → make a song more likely to be a hit:

- 🎧 Loudness, danceability, and energy push the prediction upward — the model “believes” energetic, upbeat songs succeed.

Red bars → make a song less likely to be a hit:

- 🎻 Instrumentalness and acousticness pull the prediction downward — quiet or mostly instrumental tracks tend to underperform.

The direction of the bar shows how a feature affects the outcome (helps vs. hurts), while the length shows how strongly it matters.

The model treats these effects as independent — like separate volume knobs. That’s a simplification: it can’t capture subtle combinations (e.g., quiet and emotional songs that still succeed).

💬 Discussion prompt:

Can you think of a real song that breaks this pattern? Why might the model misclassify it as a “flop”?

🎧 Example of hits that might have been missclassified as flops

| Song | Why it breaks the pattern |

|---|---|

| Adele – “Someone Like You” (2011) | Low energy and acoustic, yet emotionally powerful global hit. |

| Billie Eilish – “When the Party’s Over” (2018) | Very low loudness and valence — minimalist and dark but hugely successful. |

| Bon Iver – “Holocene” (2011) | Quiet, slow, and folk-like — critical success despite low “hit” features. |

| Lewis Capaldi – “Someone You Loved” (2019) | Piano ballad with little energy or danceability, yet chart-topping. |

Time for a break 🍵

After the break:

- Other supervised learning algorithms

- Decision Trees

- Support Vector Machines

- Neural Networks & Deep Learning

Other Supervised Learning Algorithms

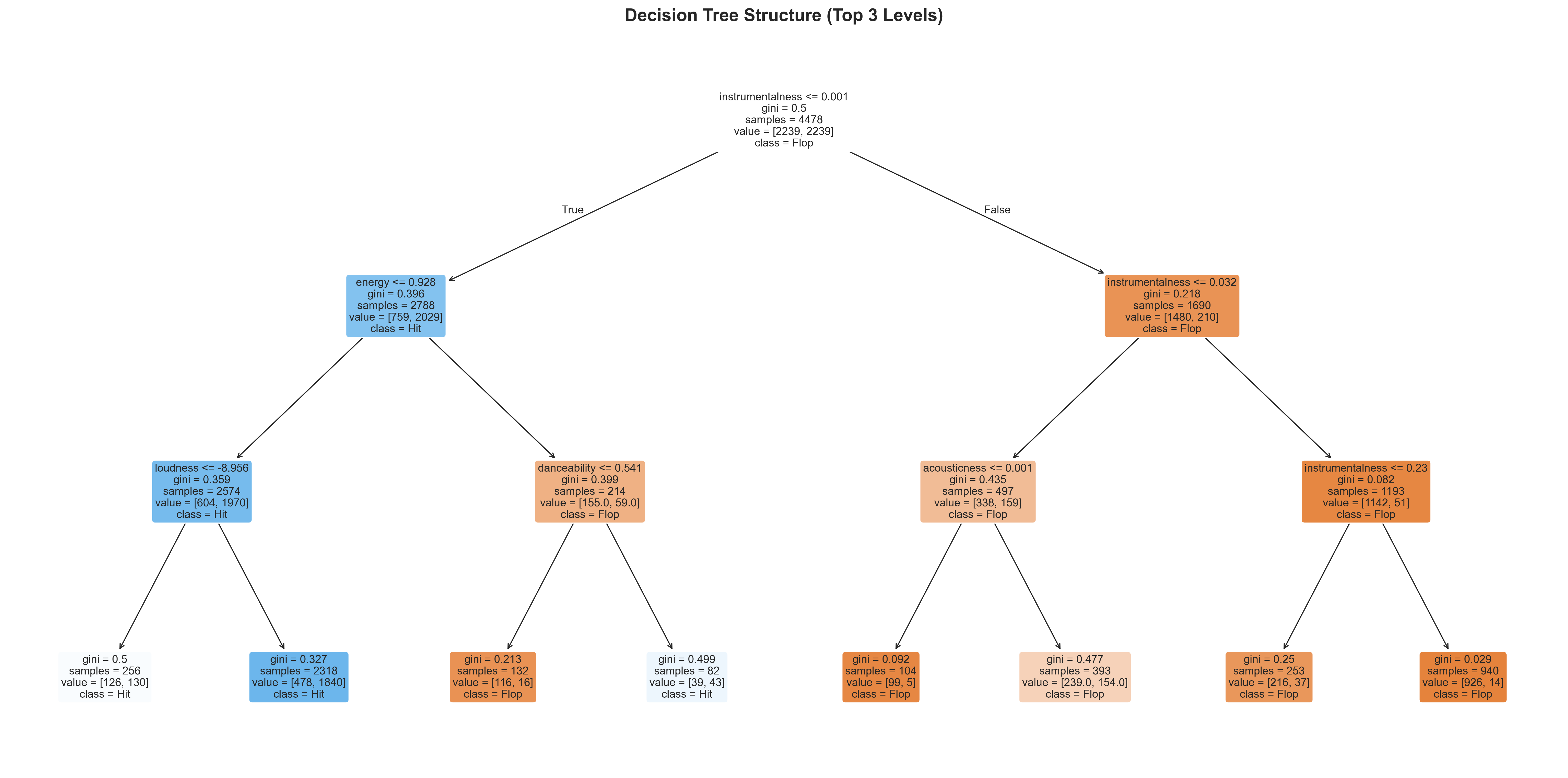

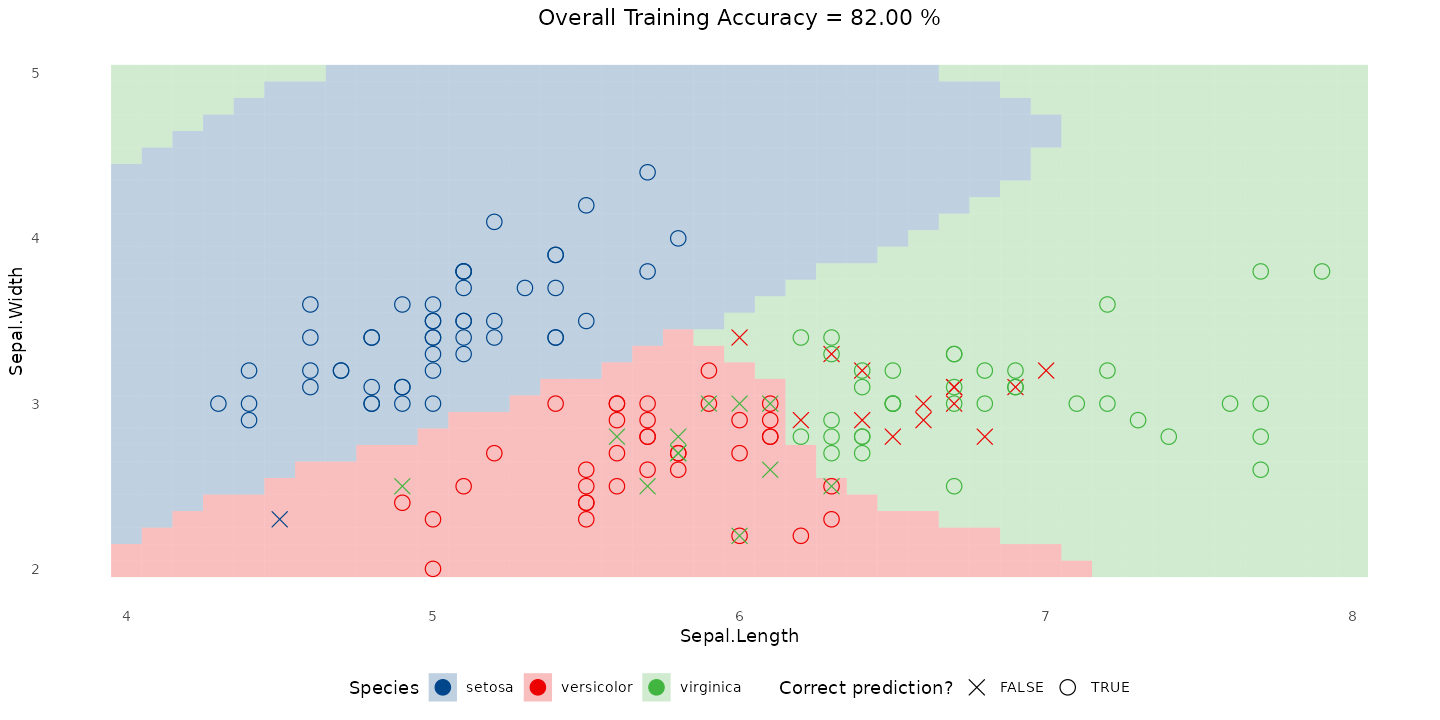

🌳 The Decision Tree Model

Decision trees make predictions by asking a sequence of yes/no questions about song features — similar to how a person might reason through a choice.

Tip

How to read this:

- The tree starts with all songs at the top.

- Each split asks a question like “Is instrumentalness ≤ 0.001?” or “Is energy > 0.7?”

- Each branch divides the data based on the answer.

- A leaf node at the bottom gives a prediction i.e “Hit” or “Flop,” depending on which group dominates.

Each step narrows down possibilities until the model can make a confident decision.

🎧 Decision Tree on Spotify Songs

Performance Metrics:

Classification Report:

precision recall f1-score support

Flop 0.86 0.70 0.77 960

Hit 0.75 0.89 0.81 960

accuracy 0.79 1920

macro avg 0.81 0.79 0.79 1920

weighted avg 0.81 0.79 0.79 1920- Accuracy is about the same as Logistic Regression (~80%).

- Tree trades a tiny bit of precision for slightly better flexibility.

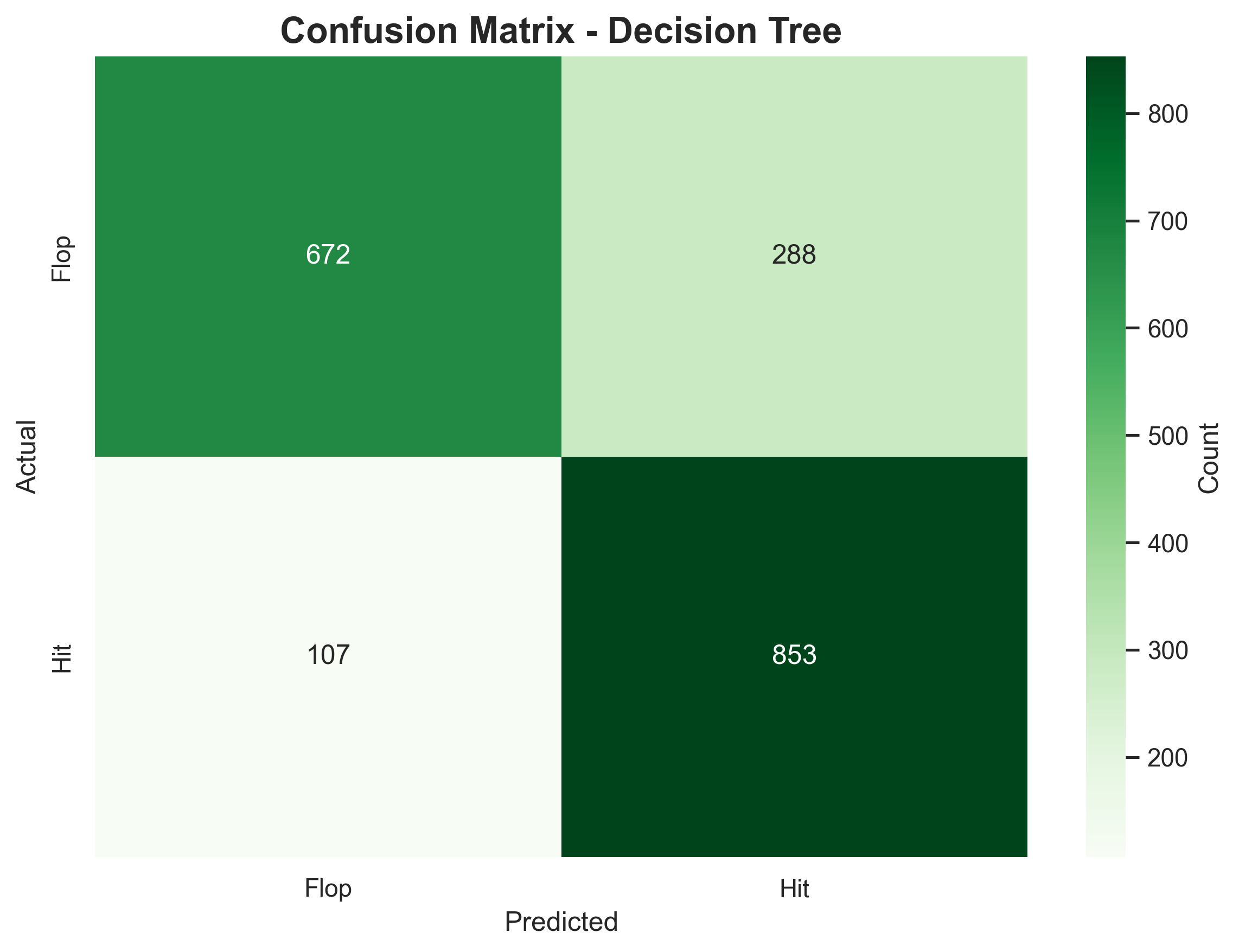

Confusion Matrix:

📊 Interpretation:

- Still confuses some flops as hits.

- Captures non-linear patterns like “High energy and low instrumentalness → hit.”

- Not more accurate — but more flexible and interpretable.

⚠️ Even if accuracy doesn’t improve, trees help us see relationships that a straight-line model can’t.

⚠️ Warning: Decision trees can easily overfit i.e memorize training patterns instead of learning general trends.

💡 Why Decision Trees Work (and Where They Struggle)

Tip

Why they’re useful

- Non-linear patterns: Trees can represent curved or step-like boundaries that logistic regression misses. → Even if accuracy is similar, they offer a different way of reasoning about the data.

- Feature interactions: Trees automatically combine conditions — e.g., “Danceable and loud” might matter more together than separately.

- Interpretability: Every decision is an if–then rule you can trace and explain.

But they have limits

- Overfitting: Deep trees can “memorize” training examples.

- Instability: Small data changes → very different trees.

- Boxy decisions: They split space into rectangles, not smooth curves.

💬 In summary: Logistic Regression draws one straight line. Decision Trees draw many rectangles — flexible but choppy. (Spoiler: SVMs will soon draw smooth curves instead.)

🌲 A Quick Note on Tree Ensembles

One tree can be unstable or biased — so modern methods combine many trees for better results.

Tip

Examples:

- 🌳 Random Forests — Many trees trained on random data slices; they “vote” on the final prediction.

- 🔥 Gradient Boosted Trees — Trees built sequentially, each one correcting the errors of the previous.

📈 Intuition:

A single tree = one person’s opinion. A forest = a team consensus — more stable and accurate.

🧠 Just remember:

“More trees → more reliable predictions.”

🗣️ Discussion: Decision Trees

- Why might a tree be a better choice for the Spotify dataset than logistic regression?

- What kinds of songs might still be hard for the tree to classify?

- If you could “prune” the tree, what might you remove to simplify it?

💬 Possible Discussion Answers

Tip

1️⃣ Why trees might be a better choice

- They capture non-linear boundaries — e.g., thresholds where energy or danceability suddenly change hit probability.

- They handle feature combinations naturally (“danceable and energetic”).

- Even if accuracy is similar, trees offer clearer reasoning: you can trace how features lead to a “Hit” or “Flop” decision.

2️⃣ What songs confuse the tree

- Songs that are ambiguous i.e moderate energy/danceability, or genre outliers (e.g., niche acoustic hits).

- Tracks that broke the mold (quiet ballads that went viral).

3️⃣ Pruning to simplify

- Remove small, deep branches that fit only rare songs.

- Focus on big, general rules (e.g., “low instrumentalness → hit”).

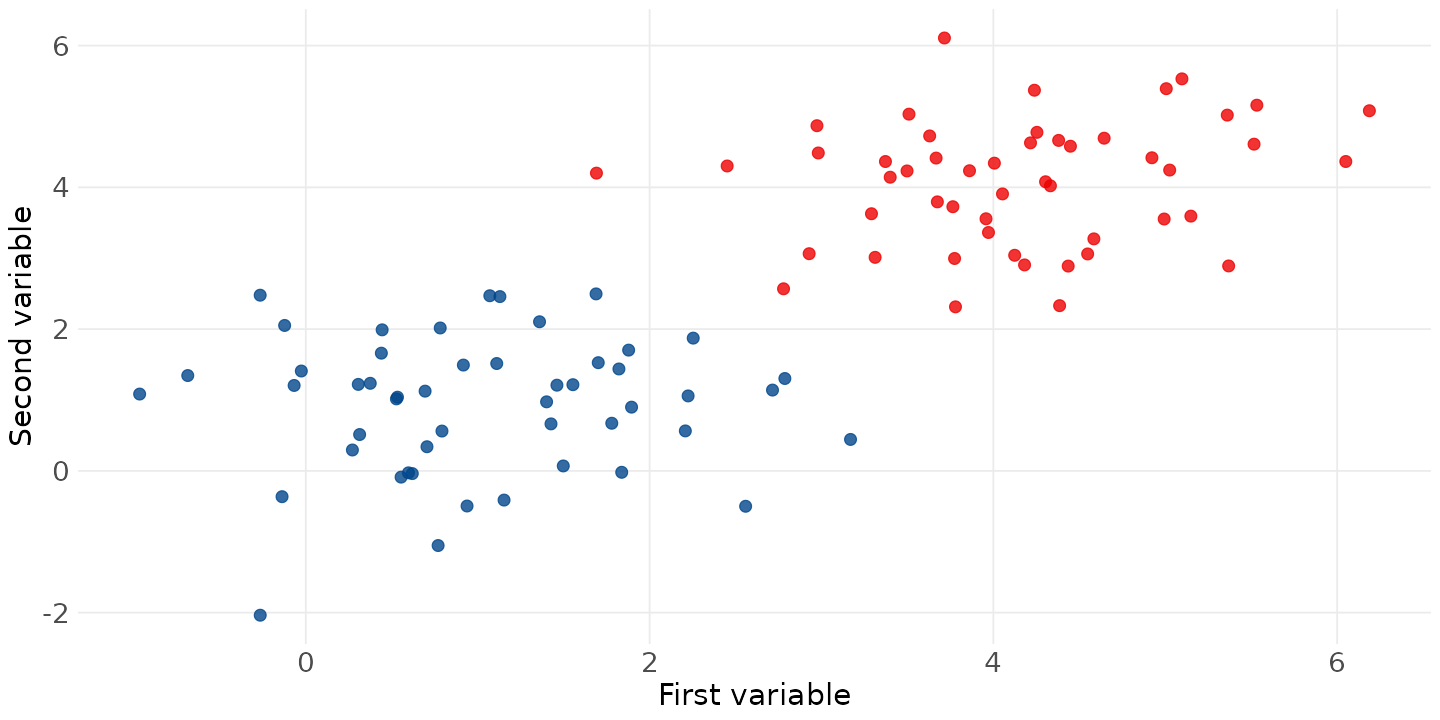

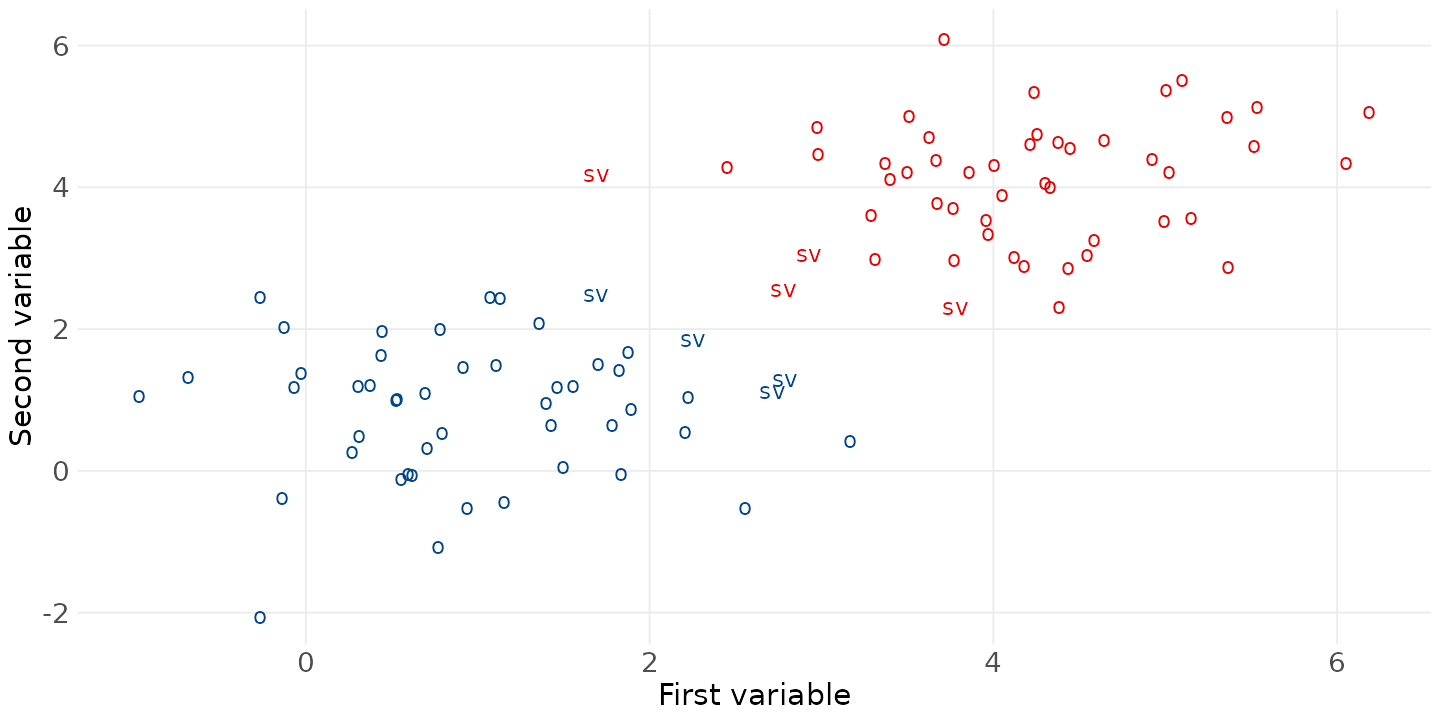

The Support Vector Machine (SVM) model

The Support Vector Machine model

Say you have a dataset with two classes of points:

The Support Vector Machine model

The goal is to find a line (or hyperplane) that best separates the two classes:

The Support Vector Machine model

It can get more complicated than just a line - using the “kernel trick” to handle non-linear patterns:

Note

- When data isn’t linearly separable, SVM can use kernels (polynomial, radial basis function)

- This projects data into higher dimensions where it becomes separable

- Powerful but less interpretable than decision trees

🎯 Spotify data and Support Vector Machines (SVM)

Idea in a nutshell: SVMs find the boundary that best separates the classes — not just any boundary, but the one with the widest margin between hits and flops.

Unlike logistic regression (a straight line) or trees (boxy splits), SVMs can bend the boundary smoothly.

Tip

How to think about it:

- Each song is a point in feature space.

- SVM draws a smooth curve (via the kernel trick) that best divides hits and flops.

- The support vectors are the most critical songs — those near the boundary that “hold it up.”

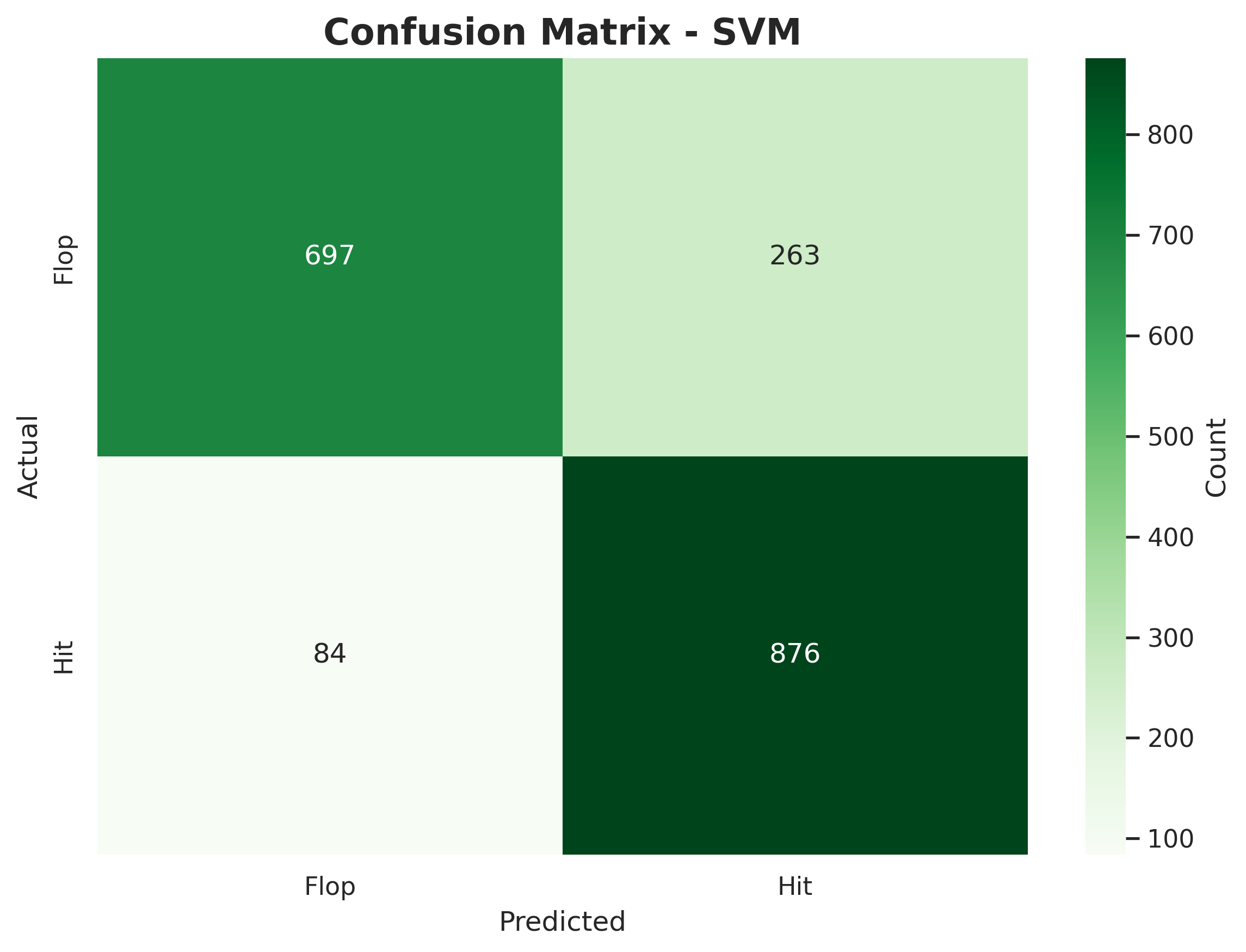

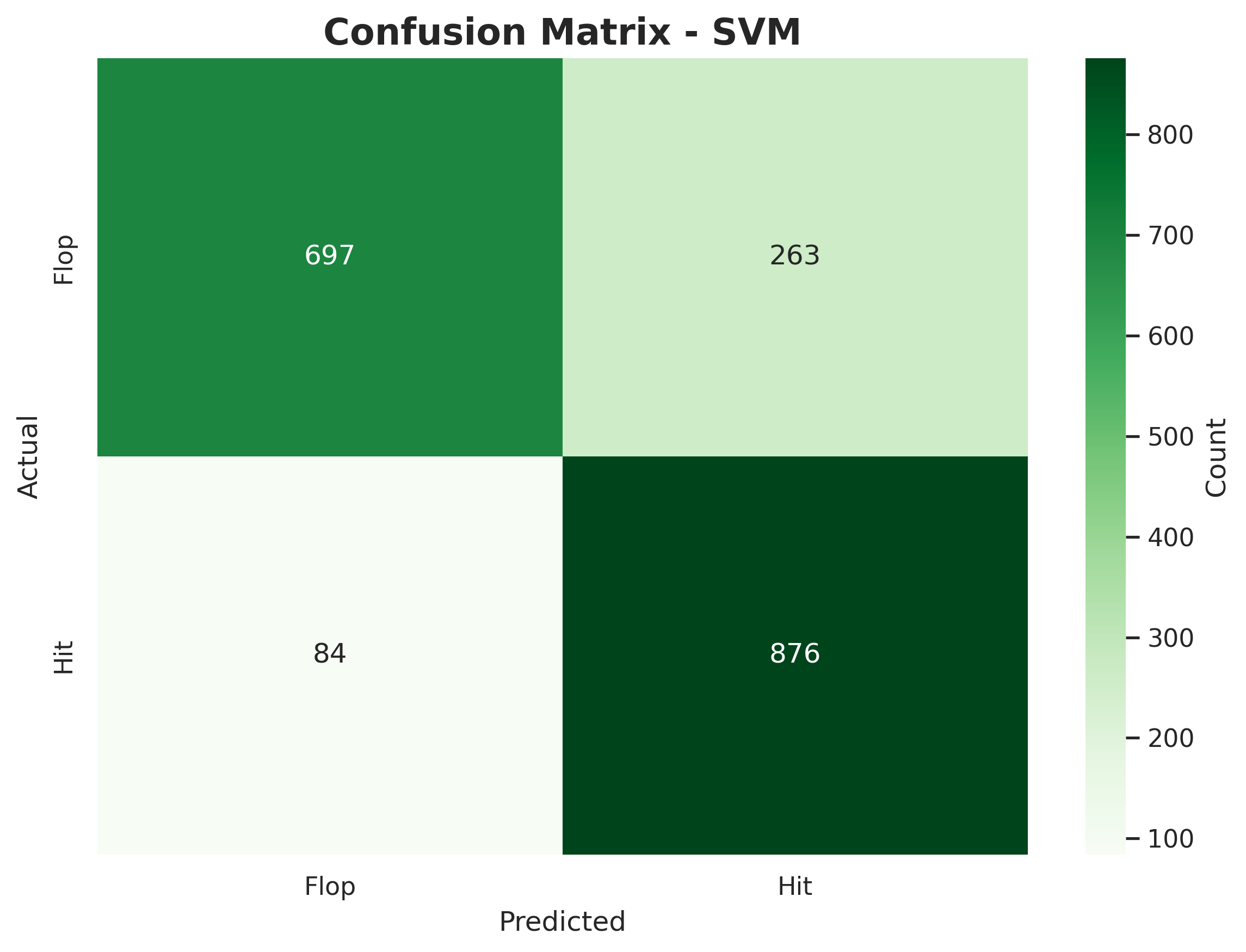

🎧 SVM on Spotify Songs

Performance Metrics:

Classification Report:

precision recall f1-score support

Flop 0.89 0.73 0.80 960

Hit 0.77 0.91 0.83 960

accuracy 0.82 1920

macro avg 0.83 0.82 0.82 1920

weighted avg 0.83 0.82 0.82 1920Confusion Matrix:

📊 Interpretation:

- Accuracy improved slightly to ~82 %.

- The SVM correctly classifies more hits than the tree or logistic regression.

- It handles curved, overlapping relationships better than straight-line or boxy splits.

- But SVMs are harder to interpret — we lose the clear “if–then” logic of trees.

💡 Conceptual takeaway: The model isn’t just smarter — it’s smoother. It balances flexibility and generalization without memorizing the data.

💡 Why SVMs Work (and Where They Struggle)

Tip

Why they help

- Smooth decision boundaries: Handle complex, curved relationships naturally.

- Robustness: Focus only on the critical “borderline” cases — the support vectors.

- Good generalization: Often better accuracy without overfitting as easily as trees.

But they have limits

- Interpretability: Hard to explain — we can’t easily visualize “why.”

- Computation: Can be slower on very large datasets.

- Tuning: Need careful choice of kernel and parameters.

💬 In summary:

Logistic Regression → Straight line Decision Trees → Boxy regions SVM → Smooth, flexible curves

🗣️ Discussion: SVMs

- Why might an SVM perform slightly better than a decision tree or logistic regression on Spotify data?

- When might a simpler model still be preferable?

- What kinds of songs could confuse even the SVM?

💬 Possible Discussion Answers

Tip

1️⃣ Why SVMs help

- Capture smooth, non-linear patterns — e.g., gradual trade-offs between energy, valence, and instrumentalness.

- Avoid overfitting by focusing on critical boundary cases rather than all points.

2️⃣ Why simpler models can still win

- Interpretability: Logistic regression or trees are easier to explain to non-technical teams.

- Speed & scale: SVMs can be slow on large datasets.

- Marginal gains: A 2 % boost in accuracy may not justify the added complexity.

3️⃣ What confuses SVMs

- Genre-bending tracks — songs with mixed traits (e.g., acoustic-electronic hybrids).

- Noisy or mislabeled data — the boundary can blur if “hit” definitions are inconsistent.

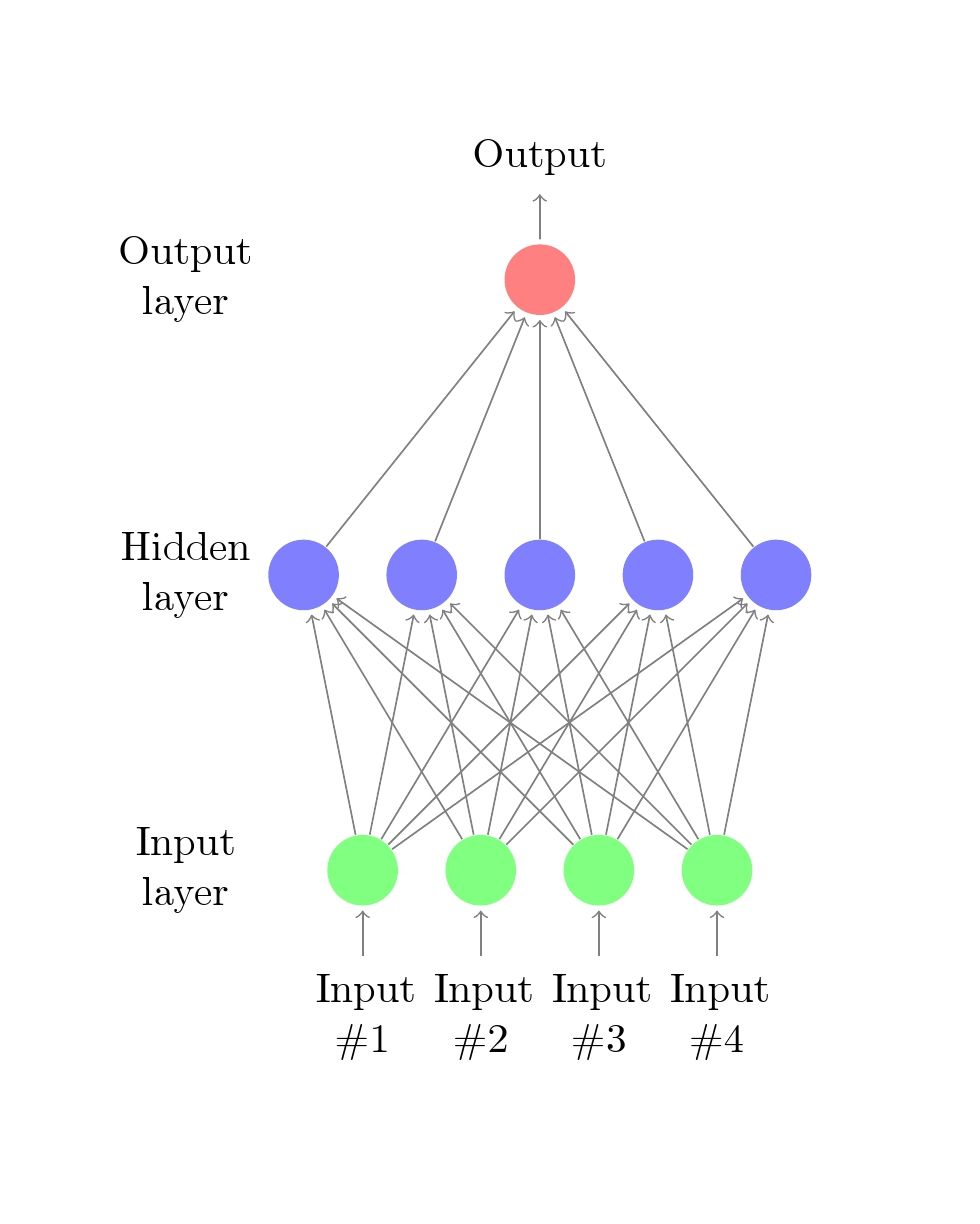

🧠 Neural Networks

Neural networks are inspired by how the human brain processes information — they consist of layers of interconnected “neurons.”

- Each neuron applies a simple mathematical function to its inputs.

- Layers combine these functions, building a chain of transformations: \[f(x) = f_3(f_2(f_1(x)))\]

- Each layer’s output becomes the input to the next — turning raw data → patterns → predictions.

- During training, the network learns the weights that make its predictions most accurate.

- A neural network with one hidden layer can already model non-linear relationships. Adding more hidden layers helps capture hierarchies of patterns in data.

Image from Stack Exchange | TeX

Note

You could compare each layer to a filter pipeline:

“Layer 1 extracts beats, layer 2 recognizes rhythm patterns, layer 3 recognizes the song’s mood.” Each layer’s function refines the previous one — like stacking musical effects.

What is deep learning

The “deep” in deep learning simply refers to many layers of learned transformations — not infinite ones.

A shallow network has just one or two hidden layers.

A deep network stacks many hidden layers — sometimes 10, 50, or hundreds, depending on the task and data size.

Each additional layer lets the model learn a new level of abstraction:

- Edges → shapes → objects (in images)

- Notes → motifs → genres (in music)

- Words → phrases → meaning (in text)

These layers are composed functions — \[f(x) = f_L(f_{L-1}(...f_1(x)...))\] where each ( f_i ) transforms data one step further from raw input toward understanding.

Warning

Trade-off: Interpretability

As we add more layers, the network can learn richer representations — but it becomes harder to see what each layer has learned or why it produced a given output.

Note

“Deep doesn’t mean magical — it means stacked.” Each layer learns from the previous one, like a factory assembly line turning raw materials into finished products.

🤔 The Challenge of Context

Deep networks are great at recognizing what is present, but not always how different parts relate.

- They process data in order — step by step, one layer at a time.

- This works well for local structure (edges, tones, nearby words).

- But they often miss long-range dependencies — how distant elements influence each other.

- Example: “The movie was great because it was emotional.” A standard network may not connect it back to movie.

💡 To capture meaning, we need models that can look across the entire input and decide which parts matter most right now.

👉 Enter the Attention Mechanism.

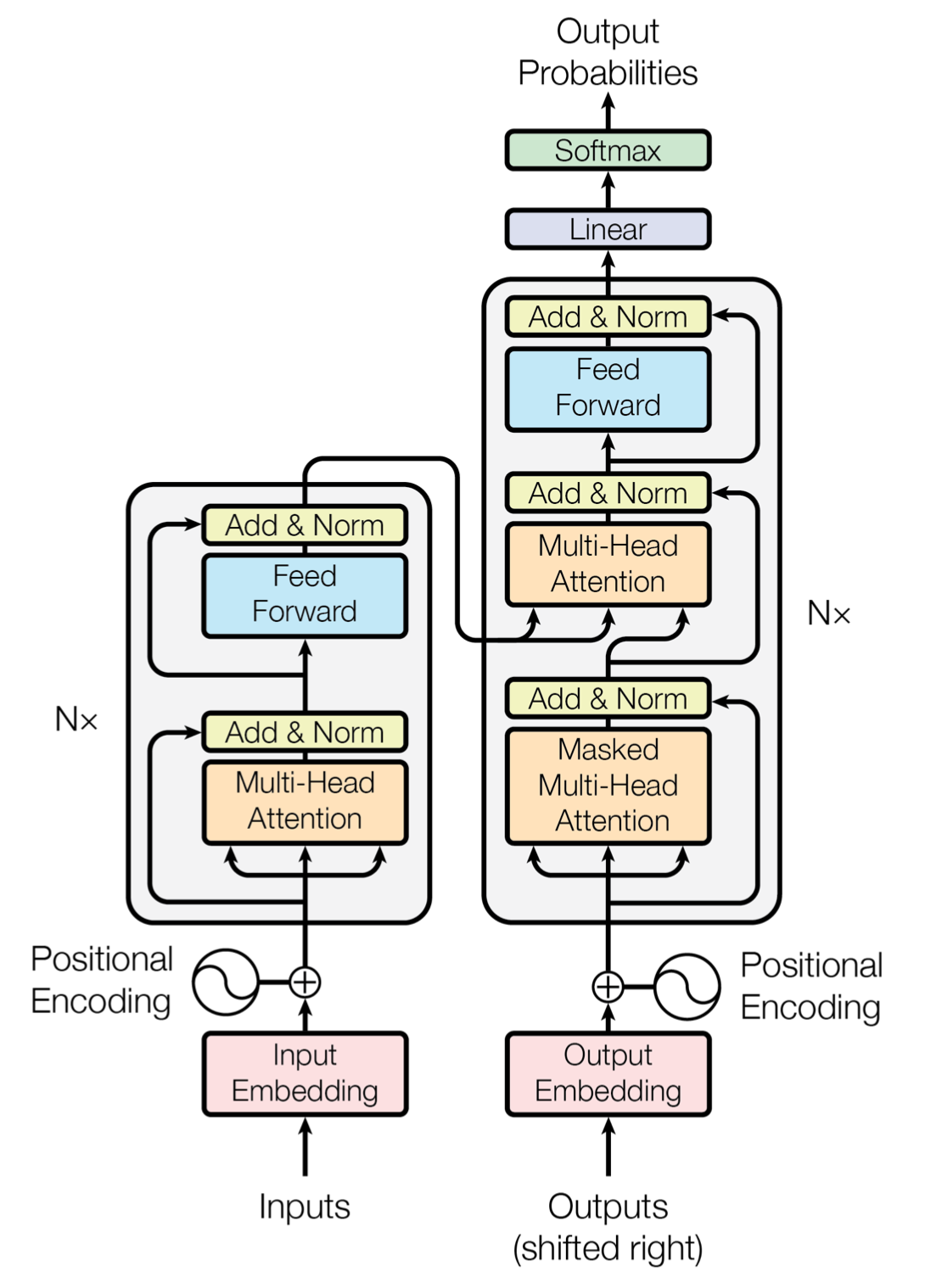

✨ Attention & Transformers

The Transformer architecture introduced an attention mechanism (Vaswani et al. 2017) — it lets the model focus on relevant context within the input.

Attention dynamically computes a new function: \[y = f(\text{input}, \text{context})\] where context is derived from relationships among all inputs.

Example:

- In “The bank by the river,” the model focuses on “river” to interpret “bank” correctly.

Transformers stack layers of attention, combining local understanding with global context — forming deep, context-aware representations.

This architecture revolutionized modern AI: powering ChatGPT, BERT, Gemini, Claude, and others.

Note

“When reading a paragraph, do we process words one by one, or in context?” Attention allows the model to look around — to weigh which parts of the input provide the most useful information.

🧩 Summary: From Simple to Context-Aware Models

| Model Type | What it Learns | Depth | Concept | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | Linear function | 1 layer | Single transformation | Simple, interpretable | Misses non-linearities |

| Decision Tree | Piecewise rules | – | Conditional logic | Transparent | Overfits easily |

| SVM | Smooth separating function | – | Curved boundary | Flexible | Harder to explain |

| Neural Network | Composed functions | Few–dozens | Layered transformations | Very flexible | “Black box” |

| Transformer | Contextual functions | Many (dozens–hundreds) | Attention-based layers | Understands relationships | Complex, data-hungry |

Tip

Each step adds more depth and context: from a single transformation → layered functions → context-aware reasoning.

Depth = hierarchy of functions, Attention = awareness of relationships.

🌟 Why Does This Work?

Our Spotify model achieved ~86–92% accuracy. But why did it perform so well?

Abundant historical data — 60 years of Billboard chart data (1960–2019). Thousands of examples to learn from.

Stable patterns — musical taste evolves slowly.

- Pop from 2020 isn’t that different from 2015.

- Danceability, energy, and valence have mattered for decades.

Reliable target — the Billboard Hot-100 offers consistent, objective labeling.

Clear feedback — we know which songs succeeded and which didn’t.

Important

But what if…

- We had no historical data?

- The target keeps changing every week?

- The system we’re modeling is new, chaotic, or unprecedented?

➡️ That’s when even the smartest models can fail dramatically.

Note

“Supervised models are only as good as their history. They don’t discover truth — they learn what has been true so far.”

⚠️ When Good Models Go Bad

Preview of tomorrow’s class

Tomorrow we’ll see what happens when data doesn’t follow the rules — using the case of COVID-19 prediction failures.

- ❌ No relevant historical data

- ❌ Rapidly evolving virus and human behavior

- ❌ Unprecedented lockdowns and testing

- ❌ Immediate policy decisions needed before data matured

Result: Many “good” models failed catastrophically. We’ll explore why — and what this teaches us about trust, uncertainty, and the limits of data-driven prediction.

Note

“Spotify worked because history repeated itself. You’ll see tomorrow that COVID broke our models because the world changed faster than the data.”

🔮 What’s Next?

- 🗓️ Week 07 class: Case Study — AI in Medicine: Predicting COVID Outcomes

- 🗓️ Week 08: Unsupervised Learning — when we don’t have labels at all

- 🗓️ Week 09: Unstructured Data — learning from text, images, and sound

Tip

Takeaway: So far, we’ve taught machines to predict outcomes when examples exist. Next, we’ll teach them to find structure — even when no answers are given.

References

LSE DS101 2025/26 Autumn Term